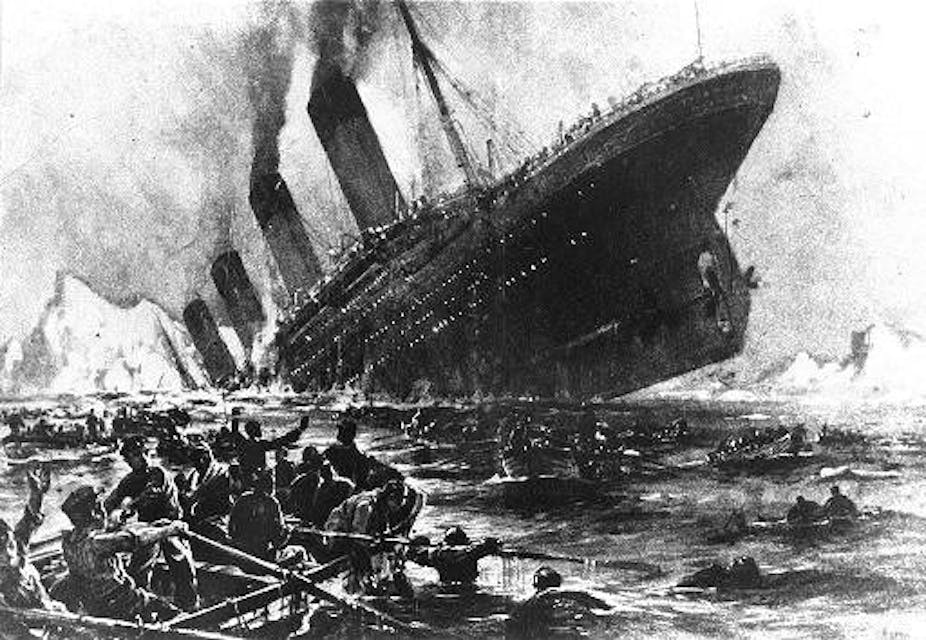

At 11.40pm local time on the cold, moonless night of 14 April 1912, the crow’s nest lookouts on board the RMS Titanic sighted a large iceberg only 500m ahead. Despite quick action, the iceberg still struck the ship aft of the bows and water flooded into the ship across several compartments. In little more than two and a half hours the Titanic sunk, taking with her 1,514 lives.

The dramatic and sudden sinking of the ship that was touted to be unsinkable provoked a great search over the next 100 years to understand how the fateful crash happened. And whether or not there was a greater risk from the number of icebergs in 1912 has been a major cause for debate.

Theories linking exceptional iceberg numbers to effects such as sunspots or extreme tides on the coast of Greenland have perpetuated the idea that 1912 was an exceptional year for icebergs, stacking the cards against the Titanic on her maiden voyage. Indeed, ships travelling through the northwest Atlantic in the days leading up to the tragedy did exchange a number of reports of ice.

But our recent research, using the iceberg records of the International Ice Patrol and an iceberg-ocean model, counters this accepted view. We’ve found that the number of icebergs in the region was neither exceptional nor unprecedented.

Following the Titanic disaster, the International Ice Patrol was established to monitor ice hazards and warn ships in the northwest Atlantic. One way they measure the iceberg hazard is by reporting the number of icebergs seen south of 48°N, a latitude extending out into the Atlantic from the south of Newfoundland. This recording has continued since 1913, and ship reports prior to this gives data reaching back to 1900 of ice in the area that the Titanic sank.

In 1912, 1,038 icebergs were reported crossing this latitude circle. In a record that varies between no icebergs and well over two thousand a year, this qualifies as a significant number. But there are several years in surrounding decades with similar numbers, including five years with at least 700 icebergs crossing the region between 1901 and 1920. The iceberg risk in 1912 then, was significant, but not unprecedented, and has been much greater in recent decades.

Source of the titanic iceberg

Our iceberg-ocean model also allows us to suggest a likely origin for the iceberg that collided with the Titanic. The longstanding view of iceberg movement in the northwest Atlantic is that icebergs from successive glaciers feed into the ocean current. Following it, they flow south along the east Greenland coast and then north along the west Greenland coast, finally circling Baffin Bay and heading south along the Labrador coast towards the Atlantic shipping lanes.

There is no way to say from which point along this long journey the infamous iceberg might have originated – it suddenly appeared out of the night and then disappeared after colliding with the Titanic. But our model allows us to use the winds and currents of the time to give the likely origins and routes for icebergs reaching the vicinity of the Titanic sinking in mid-April 1912.

It is very likely that the Titanic iceberg calved (broke off) from a glacier in one of the fjords of the southwest corner of Greenland during the late summer or early autumn of 1911 and took a more direct path, across the northern Labrador Sea, to its rendezvous with the ship.

Placing total faith in model results without supporting observations is problematic. And, even the model suggests there is a small possibility the iceberg originated from further north, in Baffin Bay, so the question of the Titanic iceberg’s origin can never be resolved with absolute certainty. But descriptions of the iceberg from survivors and the fact that five sixths of the icebergs modelled as passing 48°N latitude calved from southwest Greenland in 1912 support our model.

Icebergs ahead

More localised iceberg models are used on a regular basis by the International Ice Patrol to track icebergs in the NW Atlantic today, in combination with satellite and radar data. Even though there have been years of much greater iceberg numbers in the recent past, this constant monitoring has meant the risk to shipping is now much reduced.

Icebergs are still a threat, however, and the risk in regions without this constant monitoring is significant. As recently as 2007, the cruise ship MV Explorer sank after a collision with an iceberg in the Weddell Sea, off Antarctica and collisions elsewhere occur from time to time.

Indeed, icebergs will remain a real risk for years to come. Their number is likely to increase as Arctic glaciers respond to global warming and the sea-ice retreats. With shipping routes planned for the Arctic and the construction of coastal installations, monitoring iceberg hazards continues to be important to prevent more titanic disasters in the future.