In this series, we’ll discuss whether progress is being made on Indigenous education, looking at various areas including policy, scholarships, school leadership, literacy and much more.

There’s a large adult-sized hole in Australia’s approach to boosting literacy levels among Indigenous children and young people.

For several decades, the focus has been on increasing investment in schools and refining the ways we engage Indigenous children.

But what if the most effective way to get more kids reading and writing was to give their parents those same skills?

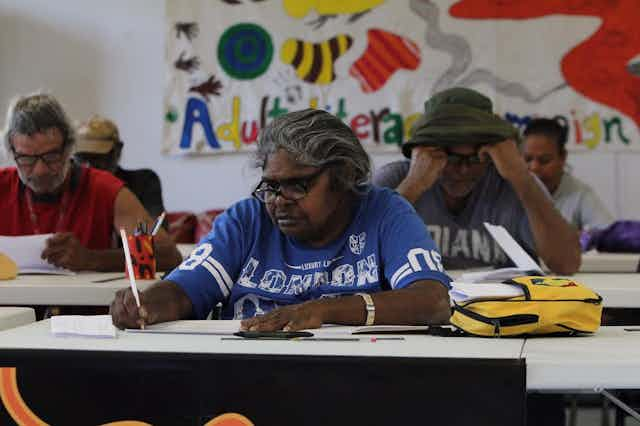

The Literacy for Life Foundation is exploring this idea through the Aboriginal Adult Literacy Campaigns the organisation has been running in western New South Wales since 2012, in partnership with the University of New England.

The Foundation uses a campaign model known as Yes, I Can!, originally developed in Cuba. It has been used in 30 countries in the global south, including Timor-Leste where it reached 200,000 people.

Each campaign is led by local Aboriginal leaders and their organisations, supported by a small team from the Literacy for Life Foundation. So far, it has run in five western NSW communities, with completion rates over 65%.

This is five times higher than Indigenous students’ completion rates for formal, accredited Foundations Skills courses run through the national vocational education and training (VET) system, which aim to get students to a similar level on the Australian Core Skills Framework.

Nationally, the completion rate for VET Certificate One courses is only 13%, and lower in rural and remote areas. These courses are mainly funded for registered job-seekers aged 15-65, missing a large number of adults who have very low literacy.

A key difference identified in a recent NCVER study is that Yes, I Can! is taught in community, by community members, with a non-formal community education approach.

Struggle to complete everyday tasks

While adults are the focus, boosting literacy levels across an entire community creates a flow-on effect into other areas, including health, employment, justice and school education.

In initial household surveys, over 50% of adults said they did not have the literacy they needed for everyday tasks such as filling in forms.

The consequences of this can be quite dire.

Law and justice officials and community leaders in these locations report that people with low literacy are less likely to go for their drivers licences, resulting in multiple instances of fines, arrest and incarceration for unlicensed driving.

People with very low literacy also struggle to understand and respond to the official communications from Centrelink and job network agencies, which determine their continued eligibility for income support.

The lack of control that people with low literacy have over their circumstances brings with it a range of health problems. At the same time, they are less likely to access primary health care services, and to follow the instructions they are given for managing medications and treatments.

Impact on children

When the adults in a community experience these problems, they have obvious consequences for their children, including on their ability to participate in school.

Most importantly, parents and other adult relations who struggle with literacy are unlikely to be able to support their children at school, in the way that parents with more literacy can.

This includes reading to children when they are very young; being able to understand and respond to notes that come home from school; taking part in parent-teacher meetings; and advocating for their children when they are having trouble at school.

It should therefore come as no surprise that children who are least likely to attend regularly and do well in school are those who grow up in households where few adults, if any, have had a good education.

When Literacy for Life Foundation ran an adult literacy campaign in the small New South Wales community of Enngonia, the local school principal was one of the biggest supporters. She said:

More parents are talking to me about school and asking for their kids to be given homework. Our pre-schoolers are using the library more, too. It’s been a great thing for the community: it’s given the adults who did miss out on their schooling a chance to catch up and have a way to relate to their children.

An ARC-funded longitudinal study of the impact of the campaigns is now underway and due for completion in 2019. This will provide more detailed evidence of the links between lifting adult literacy across a community and better school outcomes for children.

In the meantime, there is plenty of evidence already in the public domain that indicates Indigenous adult literacy levels are alarmingly low and require immediate attention.

Aboriginal community leaders began calling for action on adult literacy nearly 30 years ago, and these calls were supported in the recommendations of the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

If we are serious about getting more Indigenous kids reading and writing, we must tackle low adult literacy at the same time. If we don’t, the gap will only continue to widen.

• Read more articles in this series.