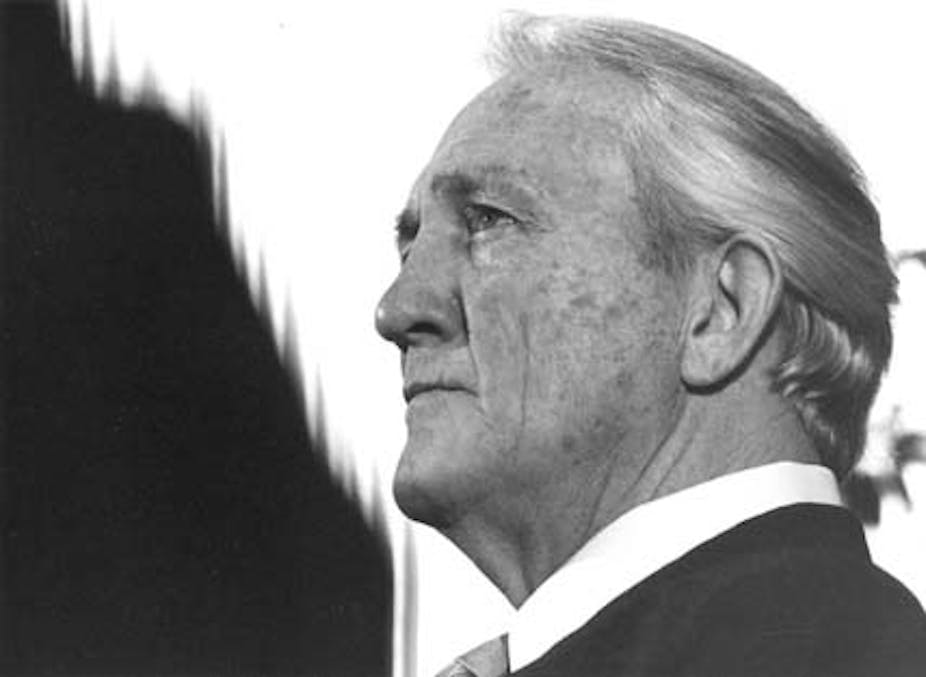

Tom Uren was a “Big Man” not only in stature but in his public life.

Uren, who has died at the age of 93, was born into a working-class household. Typical of the 1920s and ‘30s, he had a limited formal education and received his training in what he called the “university of adversity”.

Uren did not support or engage in personal diatribes or vendettas. Instead, he tried always to be true to what he saw as important social issues but in ways that were built on respect for others.

Uren first came to prominence as a peace campaigner. He had been a Japanese prisoner of war, having been captured early in the Second World War. His experience working on the Burma-Thailand railway and later outside Nagasaki, the site of the second atomic bomb dropped on Japan which he saw from the nearby prison camp, was significant in shaping his world view.

Uren was not a pacifist but stood against those who argued that resorting to force was a way to resolve differences between nations. He had experienced and witnessed the depths to which men could sink if they were denied the ordinary civilities of human relations, incarcerated and treated with little respect. He was one of the many who benefited from the example provided by Weary Dunlop, seeing him as someone who retained his integrity and decency in even the most appalling conditions.

Taking a stand on principle

Uren’s left-wing views brought him to the attention of the press and of some of the more extremist elements of the Menzies government. He was the subject of a claim that he and other ALP members of parliament were close to Soviet embassy officials. Newspaper reporting of the slander led to legal action against the Australian Consolidated Press and Fairfax, which Uren won.

The leadership Uren provided in the struggle over whether Australia should be involved in the Vietnam War was significant. In 1970 he took part in an anti-war demonstration, during which he felt that he had been assaulted by a constable. He took legal action against him, but the charge was dismissed.

Uren felt that the issue was politicised because of his stand against the war and refused to pay the costs awarded by the judge. Turning up to be jailed for non-payment of a fine for participating in an anti-war demonstration dramatised the way in which laws introduced to limit freedom of expression were being used to stifle dissent. It is a salutary reminder of the direction current initiatives could take us.

Uren’s fine was paid anonymously but clearly by someone aware of the damage that could be done to the government’s position if he was not released from jail.

Championing the fair go

Part of Uren’s approach to issues that he saw emerging in Australia was to try to understand the processes that produced the manifest inequalities to be found in the nation, in particular in those areas of Sydney in which he lived.

Uren lived in an outer-Sydney suburb near the home of Gough Whitlam. They were not close friends or factional allies but they shared the frustrations and indignities of living in areas that lacked the most basic of services.

Uren found compelling Whitlam’s analysis and articulation of the problems confronting urban Australia. He began to respond to his challenges by developing his own complementary position.

Whitlam’s setting out of the urban planning challenge in the Burley Griffin Memorial Lecture of 1968 energised Uren. Building on his experience of having to build his own house in suburban Sydney, as so many families in western Sydney had, he recognised the fundamental inequality of access to a wide variety of urban services.

Recognising the role of government

Much of the inequality grew out of the failure by the Commonwealth, especially during the Menzies years, to help the states develop housing and infrastructure services. This arose from the failure by the Menzies governments to recognise that their policies were the immediate cause of the lack of quality services.

Whitlam and Uren saw that the post-war re-conformation of the national taxation system left the Commonwealth in control of investment in the cities and, through its control over migration, gave it significant control over the demand for urban services. Both immediately recognised that the Commonwealth had a major role to play in improving the quality of life in and operation of Australian cities.

Both were also determined to develop a national role in improving the protection of the environment. Uren often referred to his concern for environmental issues; the National Estate provided opportunities to give effect to what he saw as the gentler side of his personality.

Although Uren had made a name for himself as a boxer of some ability, he reserved that aggressive side of his nature for the ring. He would often caution his departmental staff that he wanted “no hairy-chested behaviour” from them in negotiations with state officials or politicians.

Uren’s larger view of and respect for the abilities and sensitivities of his Commonwealth and state colleagues was the reason he enjoyed productive relations with state governments on a wide range of urban programs.

We could do today with Tom Uren’s skills, integrity and commitment.