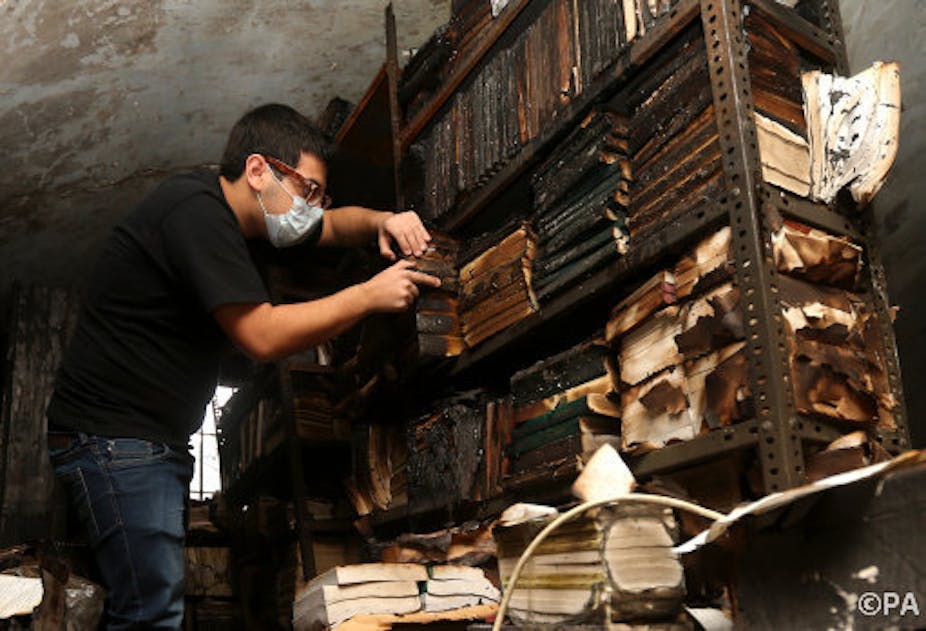

On January 4, Tripoli’s historic Al Sa’eh Library, one of Lebanon’s largest, burnt down. Two-thirds of its 80,000 books and manuscripts were lost in a fire that consumed the building.

This is no anomaly. Cultural destruction is of course a predictable by-product of political, religious, and ethnic conflict. And as the body count rises in the Middle East, so too does the loss of libraries, mosques, historic buildings, and archaeological sites.

Across the border in Syria, civil unrest has led to more than 100,000 deaths. The war has led to appalling levels of damage to historic buildings and sites, allowing people to loot archeological digs, and profit from the sale of antiquities. Two seventh century buildings, the Omari Mosque in Daraa and the Khalid Bin al Walid Mosque in Homs, were bombed and shelled extensively.

In Lebanon, it is believed the arson of the library was a product of religious extremism. Accusations against its owner, a Greek Orthodox priest, were apparently made in the mosques on the day of the attack. He was said to have a pamphlet insulting Islam and the prophet Muhammad. These accusations may have led to the violence.

Civil war and regime change often place libraries in the crossfire. In 2011, pitched battles between protesters and government troops in Cairo led to the loss by fire of one of the great libraries of Egypt, the Institut d'Egytpe, a research centre founded by Napoleon in 1789.

The building sheltered 192,000 rare books, manuscripts, journals, and illustrated documents. The most notable treasure was the handwritten 24-volume Description de l’Egypte, which was begun in 1798. Scholars laboured for twenty years on comprehensive descriptions of Egypt’s monuments and civilisation.

On December 18, 2011, there was a confrontation at the building and it caught alight. The government claimed that protestors had thrown Molotov cocktails into the library; while the protesters blamed the army. The end result was a fire which burned for twelve hours and reduced rare books to charcoal. A national treasure house was destroyed.

It was the new Library of Alexandria, inaugurated in 2002, that had the forethought to suggest digitalising the Description de l'Egypte and other important books in the Cairo library. Part of the library’s mandare is to show leadership in preservation in the Middle East.

The old Alexandrian Library was an attempt to gather all knowledge but it ultimately became an iconic symbol of the destruction of knowledge. There is a mythology that the 3rd century library was destroyed in one huge fire, but it was actually destroyed over centuries.

There was a fire set off during Julius Caesar’s siege of the city, and then at least two major cases of destruction as a function of religious extremism. Christians attacked the library as a centre of pagan learning in the 4th century, and Muslims initiated catastrophic attacks during the conquest of Egypt in 642. Libraries during war are red flags to extremists.

Is this 2000 year old pattern of loss something that will continue into the future? After all, we live in a digital age, and the process of preserving rare documents and books has begun. The lost Description de l’Egypte, for example, had been digitalised and put online. In this case, the content was not lost. But many libraries shelter unique manuscripts, documents, and maps that have never been microfilmed or digitalised.

The loss runs deeper than this. Most importantly, libraries are the repositories of the memory of a people and culture. They provide evidence of continuity, roots, and participation in the pursuit and preservation of knowledge. Libraries hold the ideas of a people, historical testimony: that which cumulatively supports identity and allows communities to conceive of themselves as a nation or a people.

Destroying a library is both expedient and symbolic. It gets rid of a rival group’s beliefs and claims to entitlement while at the same time inflicting grievous wounds on their psyche. Whoever set the library in Tripoli alight was set on the negation of a complex history, a culture, the plurality of belief systems. As an example of extremist-based destruction, the incident was not unusual.

We need to digitalise as many materials as we can so that no knowledge is irretrievably lost. But it’s not just about the content. Even assuming that the image of every text lost in Tripoli, Syria and Egypt had already been captured through technological means, we are still looking at a grievous blow to the respective societies and their collective consciousness.