There was a moment of silence in the courtyard of the College of Fine Arts when the winner of this year’s Blake Prize was announced last week. The A$25,000 prize is awarded annually for a work of religious or spiritual art. This year’s recipient, Indigenous artist Trevor Nickolls, died almost a year ago.

In considering this year’s winner, it’s worth remembering the Blake has been pushing the boundaries of the rule-makers and enforcers for 62 years.

William Blake took an idiosyncratic approach to religion – which is why, in the aftermath of the horrors of the second world war, the prize was established in his name.

Founded by a Jesuit priest and a Jewish businessman, the Blake Prize “challenges artists to explore the religious and spiritual in art”. It is open to all faiths, artistic styles, and media. By no means is it an “orthodox religion of the day” prize.

Indeed, when the prize deals with clerical figures, they are more likely to look like Rodney Pople’s Night Dance or Paul Ryan’s My Real Daddy is a Priest than to fall in step with more familiar depictions.

The Blake started at an interesting time in Australian cultural life.

In the early 1950s there was little public support for the visual arts other than prizes that were hidebound in orthodoxy. These were the years in which an academic portrait by Sir William Dargie was most likely to be awarded the annual Archibald Prize.

A prize for religious art in secular Australia was always going to be a bit of a stretch. From the very start, however, the Blake was different.

As the first work to win the prize, Justin O’Brien’s Virgin Enthroned, shows, artists felt free to explore different aspects of their faith (or lack of it). The Blake also encouraged that great eccentric artist of faith, Grace Cossington Smith, to paint some of her more visionary works.

The Blake has consistently been the only Australian art prize to look beyond subject matter to the underlying emotions guiding an artist.

Sometimes this has been controversial, as in 1961 when abstract impressionist painter Stanislaus Rapotec was awarded the prize for his response to the problem of evil with Meditating on Good Friday. Abstract art and metaphysics could be problems back in the 1960s.

Sometimes the subject matter of the Blake has been political - but it has always been personal and passionate. In 1995 the prize was awarded to George Gittoes’ painting, The Preacher, a response to a rare moment of grace in the midst of the massacres in Rwanda.

This year, painter and printmaker Franz Kempf tackled similar subject matter with his painting of a pile of abandoned, dessicated bodies, The Outrageous Has Become Commonplace.

Works dealing with social justice, or injustice, as it impacts on refugees, the dispossessed, the victims of clerical abuse – as well as a yearning for some sense of infinite beauty – all are found in this year’s exhibition.

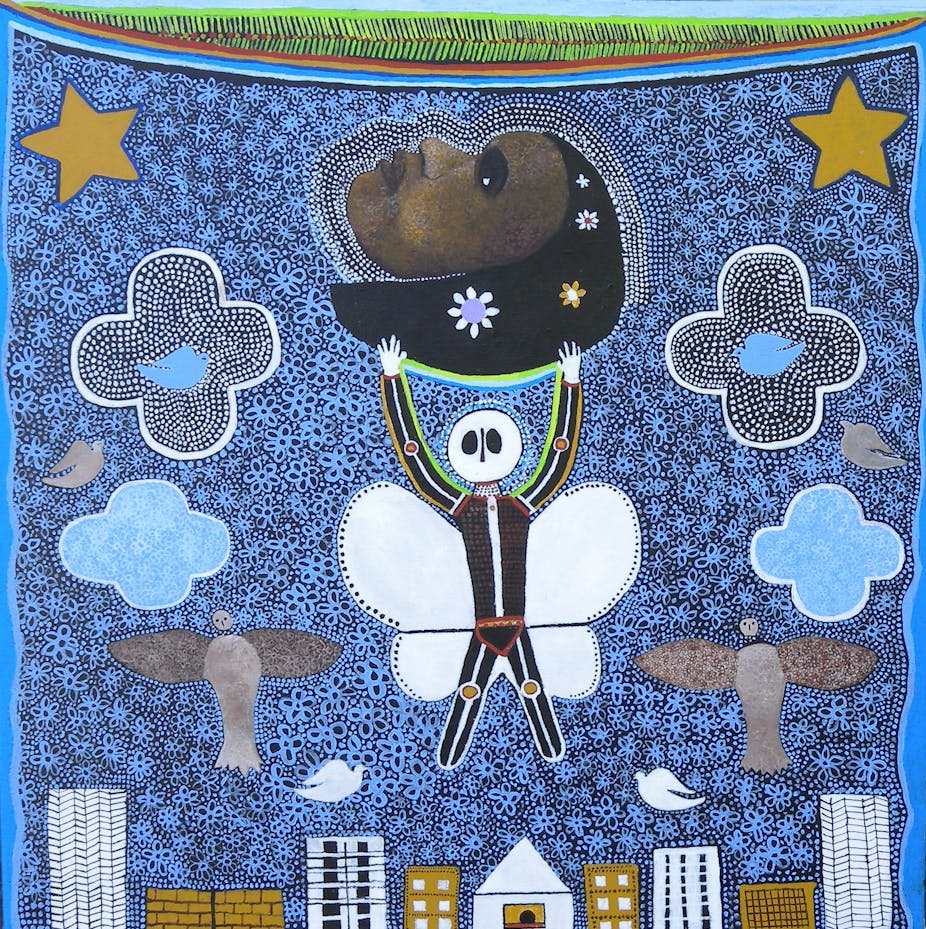

Trevor Nicolls’ Metamorphosis, is not the work that speaks the loudest, but its win is easily defensible in terms of the purpose of the Blake.

The subject is the transition between life and death, between being and unbeing. He is a butterfly; he is a spirit man. He leaves the world of pitched-roof houses and, accompanied by angelic flights of birds, goes home to a great nurturing mother.

Metamorphosis was painted by a man who knew he was dying and was entered in the competition by his estate after his death. In terms of both the subject matter and execution it is remarkably close to the visual work of William Blake himself.

Nickolls was the great pioneer of urban Aboriginal art.

Many of his paintings, especially the series Dreamtime to Machinetime, confront the viewer with the unpalatable truth of the consequences of the European invasion and how it continues to affect Aboriginal people.

With Rover Thomas, Nickolls was the first Aboriginal artist to represent his country at the Venice Biennale in 1990. Nickolls always understood how he had been able to make that massive leap from disadvantage to privilege.

The kind of art education he experienced in the 1970s gave him the intellectual and technical tools to say in paint what would have been almost impossible to write in words.

It enabled him to simultaneously communicate complex messages to both people who cannot read and write, and to cultural elites and policy makers. Because he understood the value of art education, Nickolls established a fund for an award so young Aboriginal artists can go to art school.

The Blake Prize money will go to help fund the Trevor Nickolls Art Award.