The Hazelwood coal mine and power plant has employed generations of families in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley since the end of the second world war. With the mine to close at the end of March 2017, hundreds of local residents face unemployment. When the mining stops, the pit at Hazelwood will eventually become a “pit lake” as it fills with groundwater.

Several options are on the table for the Hazelwood lake, and questions have been raised about the cost of rehabilitating the mine.

There are thousands of pit lakes on every inhabited continent, but few have been designed for people to use for recreation. Although Australians are increasingly embracing these lakes for swimming and boating, most pit lakes are unsafe and are on private property.

Germany’s brown coal mines

Depending often on the local geology, pit lakes can have poor water quality and unstable banks, which pose risks to nearby communities and the environment. However, pit lakes can also be sources of income through recreation or industry, particularly for local communities after the mining stops.

The challenge for the residents of the Latrobe Valley (and other mining regions) is to decide how new pit lakes can benefit the local economy. The challenge for scientists is how to rehabilitate these lakes for community benefit.

The coal mines of former East Germany have developed into pit lakes and can provide a vision of what Australian pit lakes might become.

Lignite (brown coal) mines were closed in East Germany after reunification in 1990, causing regional economic collapse and emigration. In an attempt to boost the local economy, the German government tasked a state-owned company with rapidly rehabilitating the landscape and filling the pits with river and groundwater for recreational use.

In 2009 the annual economic benefit of the lake district was between €10.4 million and €16.2 million. Current lake activities include swimming, boating and scuba diving. Businesses use the steep slopes of slowly filling pit lakes as vineyards, while spa hotels with lakeside boulevards cater to upmarket clientele.

Germany’s experience shows that pit lakes can lead to public benefit. However, many of these lakes require expensive ongoing active treatment, such as liming and pumping water through treatment facilities.

Due (in part) to the remoteness and low population density of Australia, this level of active treatment is unlikely to be economically feasible.

Natural rehabilitation

But active ongoing treatment isn’t the only option for improving pit lakes. Pit lakes have the capacity to change over time and become similar to natural lakes.

Pit lakes can naturally improve over decades (as seen in the coal-strip lakes of the US Midwest), if they are exposed to “passive” treatments that increase the amount of nutrients, beneficial microbes, seeds and insect larvae.

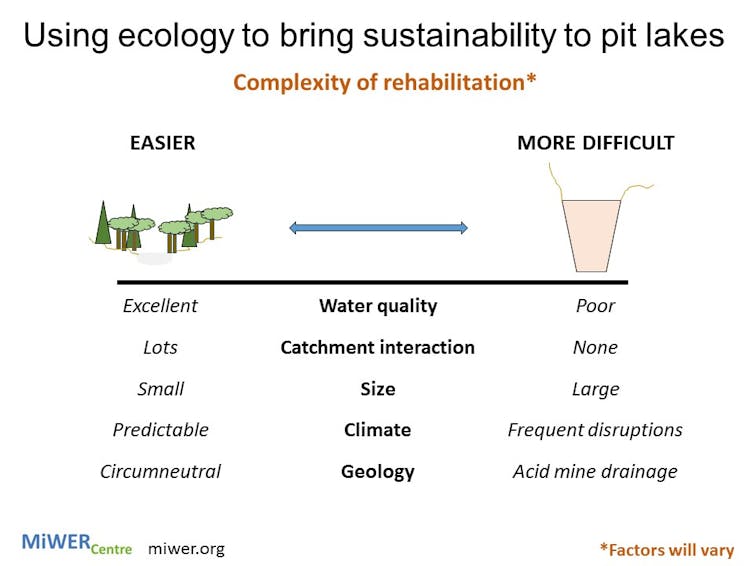

Every pit lake has a unique suite of biological and physical characteristics that make it easier or more difficult to rehabilitate. The US coal-strip pit lakes would be considered “easy” to rehabilitate because they were shallow, had large catchments and significant amounts of organic matter. However, the lakes still took decades to recover.

It’s hard to say exactly how Hazelwood will stack up on this scale without seeing modelling, but we can assume that its large size will create difficulties, as will any potential water quality issues. On the other hand, because the pit is still dry there’s an opportunity for pre-filling treatments that improve biodiversity and water quality.

For example, using heavy earthmoving equipment to “sculpt” the edge of the pit creates more natural habitats that encourage aquatic life to take hold. Careful introduction of appropriate wetland plants can enhance the system. Working with hydrologists and engineers, drainage lines connecting the pit lake to the wider catchment can provide the lake with sources of terrestrial nutrients to kickstart ecosystem development.

Passive processes tend to be slow. The challenge for scientists is to speed them up. However, many of the ecological processes that underpin pit lake development (as described above) are well-studied in artificial and natural lakes.

Turning an abandoned pit lake into a resort is not a far-fetched idea. As Germany’s mine pit projects show, communities can embrace a changing economy, and the science indicates that passive treatment systems can improve pit lakes.

The legacy of past mines and our demand for resources will ensure that more pit lakes will be produced. Ultimately, we will have to decide how we want to co-exist with these new lakes.