“Britain must prepare for war. America won’t save us this time,” declared the headline on a column in the Daily Telegraph on January 19. The Daily Mail, meanwhile, asserted on January 18 that Nato is “braced for all-out war with Russia in the next 20 years”. It cited a Nato official’s advice that civilians should “prepare for cataclysmic conflicts and the chilling prospect of being conscripted”.

The Sun has alerted its readers to the prospect of “wars in Russia, China, Iran and North Korea in five years”. In the Spectator, a recent column noted the defence secretary Grant Shapps’ assertion that the UK is “moving from a post-war to pre-war world” and suggested that “the west must stop playing Mr Nice Guy”.

Another column in the New Statesman similarly warned that a “worldwide, bipolar military conflict” will be “the organising principle of geopolitics for years to come”. It quoted Shapps as saying: “Old enemies are reanimated. New foes are taking shape. Battle lines are being redrawn.”

As fears of a new war emerge, I have delved into the newspaper print archives to explore how journalists reported the risk of conflict during the years before the world wars of the 20th century.

Press coverage in the years preceding the second world war served a generation of readers haunted by the appalling death toll of mechanised trench warfare between 1914 and 1918. Public concern was reinforced by fear of bombing, which newspapers and cinema newsreels depicted in searing images from the civil war in Spain between 1936 and 1939 and the Japanese bombing of China in 1931.

Despite the nature of Hitler’s regime in Germany, the Conservative prime minister of the time, Neville Chamberlain, was determined that British newspapers must promote appeasement. Press management became a political priority for Chamberlain.

He was helped to achieve it by two key lieutenants. Downing Street press secretary George Steward and Sir Joseph Ball, the chairman of the Conservative Research Department, worked closely with the prime minister to persuade British newspapers that appeasement was in the national interest. Chamberlain insisted that hostility to his approach would weaken Britain’s influence abroad.

Read more: How Neville Chamberlain's adviser took spinning for the PM to new and dangerous levels

Munich agreement

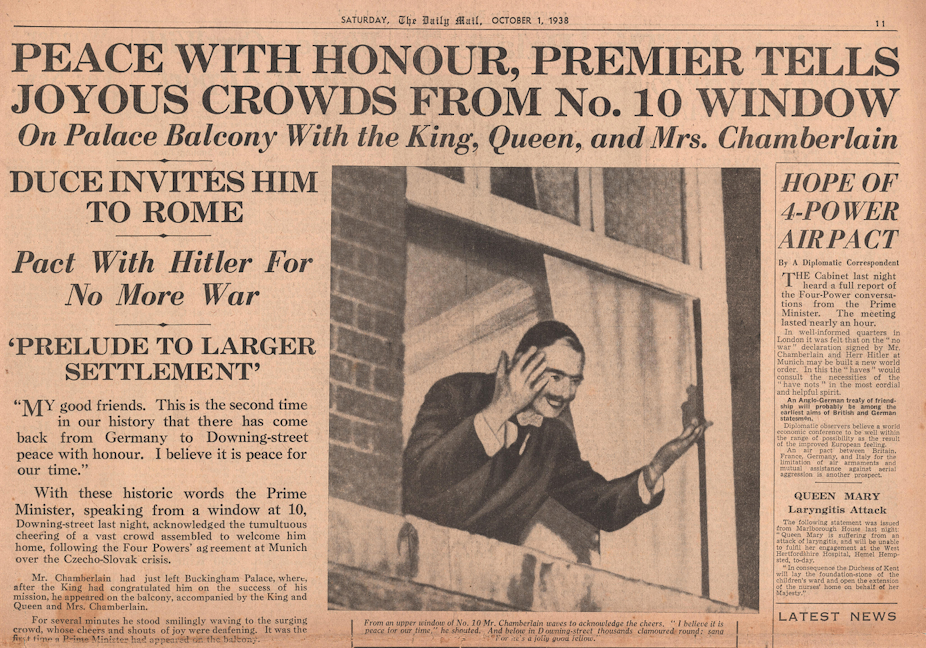

When Chamberlain negotiated the notorious Munich agreement with Hitler in September 1938, The Times did not oppose the transfer of the Sudetenland to Germany without Czech consent. Instead, Britain’s most prestigious establishment broadsheet declared that: “The volume of applause for Mr Chamberlain, which continues to grow throughout the globe, registers a popular judgement that neither politicians nor historians are likely to reverse.”

It predicted that Chamberlain’s diplomacy would end in “an era when the race for armaments will be seen for the madness that it is and will be abandoned because it has ceased even to be profitable”.

The mass market Conservative Daily Mail chastised Labour’s Clement Attlee for complaining about the “shameless betrayal” of the Czechs and accused Attlee of issuing “frothy diatribes”. It promoted Conservative optimism that the agreement would guarantee peace.

The liberal Manchester Guardian loathed Hitler and harboured grave doubts about appeasement, but it could see no practical alternative. In a leader column on October 3 1938, it cautioned:

Now that the first flush of emotion is over it is the duty of all of us to see where the ‘peace with honour’ has brought us. The Prime Minister claims that it has brought us ‘peace for our time’. It is an inspiring claim, and if it proves to be a just one, he will have earned a place in history.

The following day’s edition of the popular left wing Daily Mirror was similarly unconvinced. It feared the “further strengthening until it becomes invincible of the Nazi domination of Europe”. The Mirror believed peace could only be secured by military strength brought about by rapid rearmament, but it could identify no alternative to compromise and deterrence. It feared a “world so armed and so explosive that it will blow itself to bits”.

In a subsequent leader on October 7, 1938, The Guardian hoped new weapons and additional recruitment to the armed forces might reinforce British diplomatic influence. However, it warned that if British foreign policy did not change substantially, “ordinary men and women” would not be persuaded that “the diplomacy our armaments are to serve” would work.

Doomed to repeat mistakes?

Journalism’s failures between 1936 and 1939 were less appalling than the jingoistic press campaigns that preceded the first world war and continued throughout it.

Between 1914 and 1918, newspapers downplayed misery and extolled victory. Soldiers found their behaviour hard to forgive. Such reporting promoted the belief that newspapers could not be trusted to tell the truth. It won newspapers a reputation as the main backer, and perhaps even an instigator, of conflict.

Later, their failures during the era of appeasement meant that British newspapers were not entirely trusted by their readers when the second world war was declared in September 1939. They were widely read but little loved.

In highlighting the risks facing the world as Ukraine resists Russian aggression and fighting rages in Gaza, newspapers suggest that they have learned from conflicts of the past. They are neither encouraging war nor disguising the possibility that Nato may be called upon to defend borders and democracy.

Britain has better newspapers than it had in 1914 or 1939. Would their editorial strengths survive the outbreak of war? I fear that now – as it was in the past – truth may still be the first casualty.