NATO foreign ministers have agreed to suspend all cooperation with Russia and bolster their defence posture in the Baltic states and Poland. This move reflects the continuing perception of a Russian threat to Ukraine, a point made abundantly clear in a statement by the German chancellor Angela Merkel – which is particularly significant given that Germany is usually seen as Russia’s closest ally in the West.

The NATO decision follows an inconclusive meeting in Paris on Sunday between US secretary of state, John Kerry, and his Russian counter-part, Sergei Lavrov about finding a diplomatic solution to the current crisis in Ukraine. No real breakthrough was achieved, but Moscow and Washington committed to keeping their talks going. Unlike Kiev, Kerry did not explicitly reject Russian proposals for the federalisation and neutrality of Ukraine.

Western unease, and the responses so far, reflect lingering concerns over Russia’s longer-term intentions. With few exceptions, most analysts expect similar land grabs, based on the assumption that Vladimir Putin and his inner circle are intent on restoring as much of the geographical zone of influence that the Soviet Union had as possible. Putin’s speech justifying the annexation of Crimea certainly lends credence to such assumptions – as does the track record of Russian policy from the 2008 war with Georgia and the subsequent recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, to the aggressive push for the creation of the Eurasian Union (so far including Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus), to the annexation of Crimea and the aggressive rhetoric about Russia’s rights to protect ethnic Russians and Russian-speakers outside the Russian Federation.

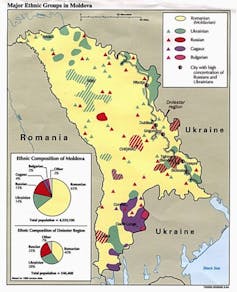

A lot of this debate and commentary has centred on Moldova and its break-away Transnistrian region as being high on Moscow’s list of most likely targets.

This makes sense in many ways. Russia has a military presence in Transnistria in the form of remnants of the 14th Army, supposedly guarding Soviet military equipment and munitions from the Soviet period left there at the time of the dissolution of the Soviet empire in 1991. Russian forces are also one component of a CIS peace-keeping force set up at the end of the brief violent conflict between Moldova and Transnistria more than two decades ago. Military exercises by these forces are obviously adding to existing tensions.

According to a 2004 census, there is also a sizeable ethnic Russian population in Transnsitria (approximately 30%, with similar numbers of ethnic Ukrainians and ethnic Moldovans). Around 90% speak Russian and many also hold Russian passports. In a referendum in 2006, some 97% of the Transnistrian population expressed a desire for independence. While these figures clearly suffered from Soviet-style inflation, there is little doubt that the majority of the people in Transnistria do not, at present, want to be part of a Moldovan state. More than 20 years of separation have clearly contributed to a pre-existing sense of a distinct regional identity.

Yet, during the past 20 years, a fairly stable status quo had been established between the authorities in Transnistria and the Moldovan government. A status quo, moreover, that saw many gradual and incremental improvements, facilitating relatively free movement of goods and people across the River Nistru and enabling Transnistrian companies to enjoy the same Autonomous Trade Preferences with the European Union as Moldovan ones for the past six years, provided they registered in the Moldovan capital, Chisinau.

European ties

Moldova has moved increasingly closer to the European Union, a process that was begun under the previous communist government and has been accelerated by the current Alliance for European Integration. With negotiations on an Association Agreement completed last year and now ready for signature in June, visa liberalisation approved, and a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement likely to come into force after a transitional period in January 2016, Moldova has embarked on a path similar to Ukraine. From the Kremlin’s perspective, assuming this is all about restoring a Soviet-like zone of influence, this must be worrying.

Moreover, there is also a renewed strategic value in having control over Transnistria (and by extension, Moldova), as this gives the Kremlin additional leverage over Ukraine. This, however, is counter-balanced by the fact that Russia has no direct access to Moldova and Transnistria, landlocked as they are and wedged between a deeply anti-Russian western Ukraine and Romania, a member of both the EU and NATO.

Moscow’s options

Moldova and Transnistria clearly are close to, if not at, the top of the Kremlin’s list. So what might Moscow do? One scenario is a military push through eastern and southern Ukraine, capturing the port of Odessa and moving into Moldova and Transnistria from the south. A version of this scenario might be simply to take Odessa. This would be a highly risky strategy for Moscow, triggering most certainly open war with Ukraine which would likely receive significant Western political, economic and military support (although without full Western military engagement). Russia’s military build-up on the eastern borders of Ukraine would indicate that Moscow wants this to be seen as a potential option for the future, even though the Kremlin has promptly denied any intention to invade Ukraine.

A second scenario could involve the continuation of a status quo of sorts, albeit one with a noticeable destabilisation of the political and security situation in both Moldova and Transnistria. This would be a relatively low-cost/high-benefit option for the Kremlin. It could also pave the way towards the first scenario, creating the very conditions under which Moscow could claim that it needs to act in order to protect ethnic Russians, Russian-speakers, and Russian passport holders.

The strategy, however, would not be risk-free either. While a large number of Moldovans favour closer ties with Russia, this does not equate with a desire to become a client state of Moscow, let alone a province of the Russian Federation. The calculation may be somewhat different for the residents of Transnistria, but the economic consequences of cutting all ties with Moldova and the EU would be devastating, given that a total of over 70% of all Transnistrian exports go west.

A third option for the Kremlin would be to work towards a settlement of the conflict, with the aim of keeping Moldova permanently outside the influence of the EU and NATO. This could be achieved by simultaneously keeping up the pressure on Moldova (under scenario 2) and encouraging a gradual rapprochement between Tiraspol and Chisinau that would create a fully federal Moldova (with the southern region of Gagauzia possibly being a third and the northern region of Bălţi/Belz being a fourth federal entity) in which federal subjects can exercise a veto over key foreign policy decisions –- such as EU or NATO membership, or even closer ties with either of these organisations.

It is in this context, that we need to see the new talks on Ukraine, especially given Russian proposals for the country’s neutrality and federalisation and Moscow’s insistence that the next round of the so-called 5+2 Talks on Transnsitria should go ahead as planned on 10 and 11 April.

The third scenario outlined above may, therefore, appear to be the most likely and palatable – and it is, given the other options considered. Yet, it would mean that Moldova would essentially lose the ability to make a free and sovereign choice over its future strategic political, military, and economic direction. If this is to be avoided, the West needs to send a much clearer message to Moscow and back it up with credible policy. The question, however, is whether policy makers from Berlin to Brussels, London and Washington think that Moldova is worth such a tougher line.