This is the first in a new series called “Under the Influence”, in which we ask experts to share what they believe are the most influential works of art in their field. Here, Afrofuturist Michael Shakib Bhatch introduces Ray Lema’s “Nangadeef”, a record that was released in 1989 on Mango Records.

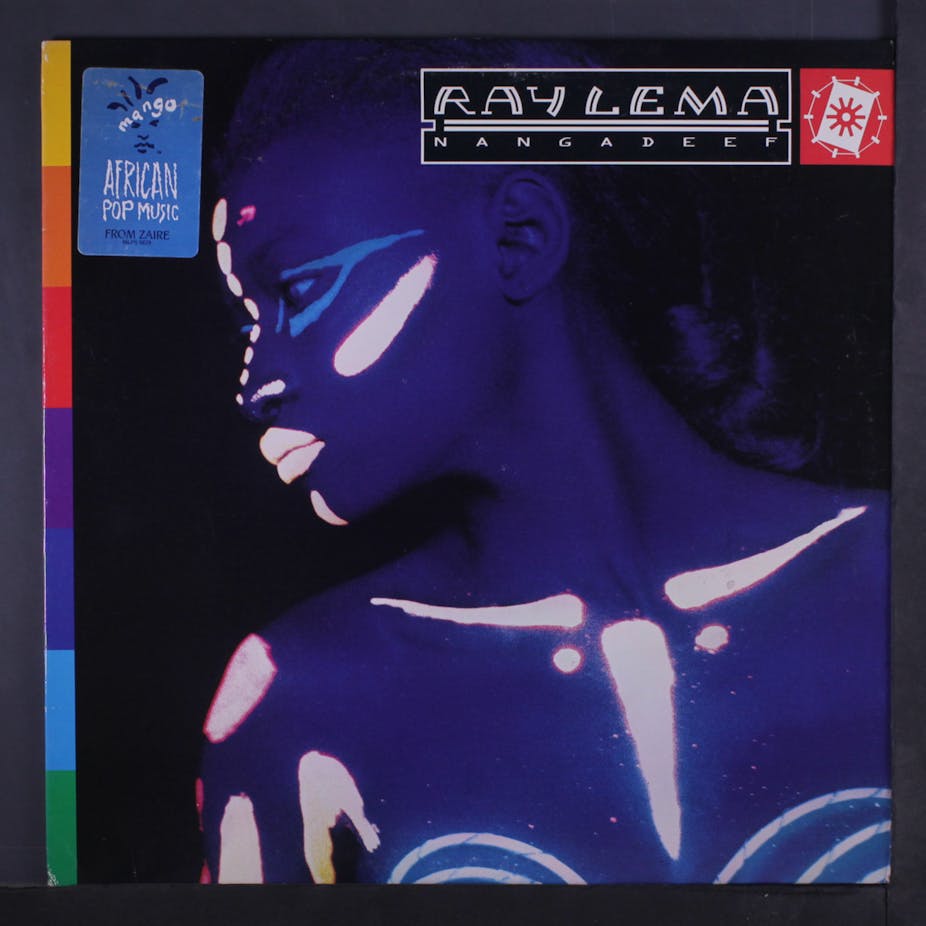

“Nangadeef” is a nine-track album by progressive Congolese cultural icon, ethnomusicologist and virtuoso musician Ray Lema. It features classic Afrofuturistic artwork on the cover, designed by London-based photographer Richard Haughton.

The album was released four years prior to the coining of the term “Afrofuturism” by cultural critic Mark Dery. This is significant to note, as academic investigation and discussion around this term only gained momentum in the late 1990s. The conversation around this album is precisely centred on the fact that the clearly Afrofuturistic musical work “Nangadeef” is generally overlooked in the academic discussions about Afrofuturism in Africa and in the diaspora.

The album features an impressive lineup of African, American and British musicians. They worked incredibly well together to mould Lema’s vision for the record. The Mahotella Queens, Jesse Johnson, Courtney Pine and session musicians from across the continent create an amazing fusion of traditional African music and futuristic sounds.

The album’s soundscapes can be described as traditional African music fused with contemporary Western sounds. This fusion is set to a strong overarching backdrop of electronica, which gives it a distinct Afrofuturistic character. Whether intentional or not Lema has created a masterpiece that will, for years, be dissected by anyone interested in Afrofuturism and its almost independent development on the continent.

Why it is and was influential

The album offers the listener an opportunity to explore African musical fusion that is “future concious”. It does so by giving an aural insight into both electronic music and traditional African sounds simultaneously and with equal vigour. The album explores Afrofuturistic soundscapes within an African music context almost independently from the Afrofuturistic soundscapes explored by black artists in the diaspora.

It offers another dimension to how we view the development of Afrofuturism in Africa, and in other parts of the world. It also gives us insight into how African musicians were thinking about the future sound of African music in the late 1980s.

Musically, it offers us foresight into how musical styles on the continent might fuse, alter and develop as music technology and the African context changes.

Why it’s still relevant

Afrofuturism has been dissected and made sense of by scholars across the globe for the past 18 to 20 years. Currently there is a rather pressing need to understand how it developed on the African continent. Also, if its development in Africa is different to its development elsewhere. Increasingly we need to understand it within our own context. We therefore need to explore the works of our own artists to do so.

Up until recently discussions about Afrofuturism have almost always been centred on prominent Afrofuturists in the diaspora. Examples are Sun Ra, Octavia Butler, Funkadelic and Lee “Scratch” Perry.

There has been a general neglect of Afrofuturists on the African continent who have been instrumental contributors to the ever-evolving story of this phenomenon. Here artists like Francis Bebey, Ray Lema, Alec Khaoli and William Onyeabor spring to mind. “Nangadeef” is relevant today because it is a largely unexplored repository of Afrofuturistic data.

Also, pan-African collaboration and cultural fusion in Africa is extremely necessary for various socio-historic reasons. Africans have, for a long time, been subject to internal divisions imposed upon us by our colonial masters. These divisions have prevented us from understanding each other’s cultures, traditions and overwhelming similarities. These divisions have also fragmented and isolated the elements that constitute our collectively rich musical identity and heritage.

An album like “Nangadeef” allows us to imagine our musical identity outside of our historic and present divisions. If anything, the album is futuristic in its ability to make the listener forget that Africa is indeed a troubled continent with a history of colonially imposed divisions that make the pan-African cultural ideal seem far fetched. It tells us that we have great music on the continent that is yet to be explored, fused, experimented with and listened to.

“Nangadeef” is still relevant today as the sounds on the record can be heard on later and contemporary recordings, both inside and outside of the continent. Think Mbongwana Star and Rocket Juice and the Moon. Outside of being a possible relic of cultural history, the album still has musical appeal.

Sonically, it remains largely unexplored, despite its genius. It is easy to see how the album may have been misunderstood and even overlooked on release in 1989. Today it yields insight and intrigue for the cultural scholar, the discerning listener and the dancefloor “shazammer” alike. I would go as far as saying that the album needs to be sampled by African electronic, neo-soul and hip-hop artists who are looking for Afrofuturistic sounds from the continent.

My relationship with the album

I bought the record about a year ago from a prolific African music collector and ex-record label, A&R Jumbo van Reenen. The first thing about the record that grabbed my attention was the cover. It seemed so tribal and futuristic, which is right up my alley. I then gave the album a listen only to discover that the music mirrored my perception of the cover art. Since then the album has been a favourite in my household.

“Nangadeef” intrigued me because I’m fascinated with Afrofuturism and how it manifests in music, and also because of its pan-African feel. I love how the record educated me and entertained me 27 years after it had been released. It feels so new to me, both sonically and conceptually. It also got me thinking about how the traditional and progressive can coexist in the present time, and do so quite well.

Birds of a feather

The album is by no means the only one that does what it does. However, it is a brilliant example of how African artists were pushing boundaries and being progressive. To further expand our understanding of the Afrofuturistic pan-African ideas and sounds featured on “Nangadeef” I would recommend the following albums:

- Ray Lema – “Medecine” (1985)

- The Chris Hinze Combination – “Saliah” (1984)

- The Art of Noise – “Below The Waste” (1989)

- Mandingo featuring Foday Musa Suso – “Watto Sitta” (1984)

- “Om” Alec Khaoli – “Say You Love Me” (EP) (1985)