This is the second in a new weekly series called “Under the influence”, in which we ask experts to share what they believe are the most influential works of art in their field. Here, Zen Marie introduces two of jazz trumpeter Miles Davis’ albums, “Bitches Brew” (1970) and “Live-Evil” (1971).

Miles Davis’ “electric period” was book-ended by his records “In a Silent Way” (1969) and “Agharta” (1976). Dubbed “Electric Miles”, it was unpredictable, challenging, groundbreaking – funk’s James Brown meeting art music’s Karlheinz Stockhausen, with psychedelic rocker Jimi Hendrix gatecrashing.

Like the respectable free jazz, his music was experimental and out there during this phase, but unlike the former, it was “electric, beat-heavy, and marketed to kids”, as music doyen Robert Christgau put it. And it was not loved by all, especially jazz critics – “thus obviously worthy of suspicion if not contempt”. Another reason these jazz ideologues dismissed “70s Miles is that the bands aren’t stellar”, according to Christgau.

I beg to differ.

“Bitches Brew” and “Live-Evil”, released in sequential years and part of the “Electric Miles” period, saw Davis gather a truly legendary cast of musicians to produce two of the most challenging collections of music – ever. In fact, what they offer goes beyond music – the albums are challenges that go beyond the ordinary and are an invitation to enter the sublime.

First, it’s worth mentioning the musicians, some of whom are featured across both albums: Airto Moreira; Billy Cobham; Bennie Maupin; Chick Corea; Dave Holland; Don Alias; Gary Bartz; Harvey Brooks; Herbie Hancock; Hermeto Pascoal ; Jack DeJohnette; Joe Zawinul; John McLaughlin ; Jumma Santos; Keith Jarrett; Larry Young; Lenny White; Michael Henderson; Ron Carter; Steve Grossman; and Wayne Shorter.

For those not into jazz, this is like the Real Madrid (or Barcelona) of line-ups. For those not into football, its like a G8 summit. For those not into politics, its like the Triwizard Cup. For those not into “Harry Potter” … well, I think you get the picture.

The talent, mastery and prowess of the personnel on these albums can’t be emphasised enough and it is a credit to Davis that he managed to pull such heavyweights together.

Why is/was it influential?

The stature and pedigree of the musicians is not why I chose these works for “Under the influence”. When I first heard the music on these albums, I had no idea who they were nor the significance of the gathering. For me the two albums were strange and alien oddities that made absolutely no sense.

They did not sound the way I thought music should, the tracks were too long, the melodies syncopated, discordant, ghostly, disconcerting and at times psychotic. As far from smooth jazz as you can get, the form of this offering was something more like a pack of wild animals hooting, barking, howling and screeching: baying for carnal, bloodthirsty desires to be satiated. This was not a classic Miles Davis Quintet type of gig … the music was complex, nuanced, elaborate and ambitious.

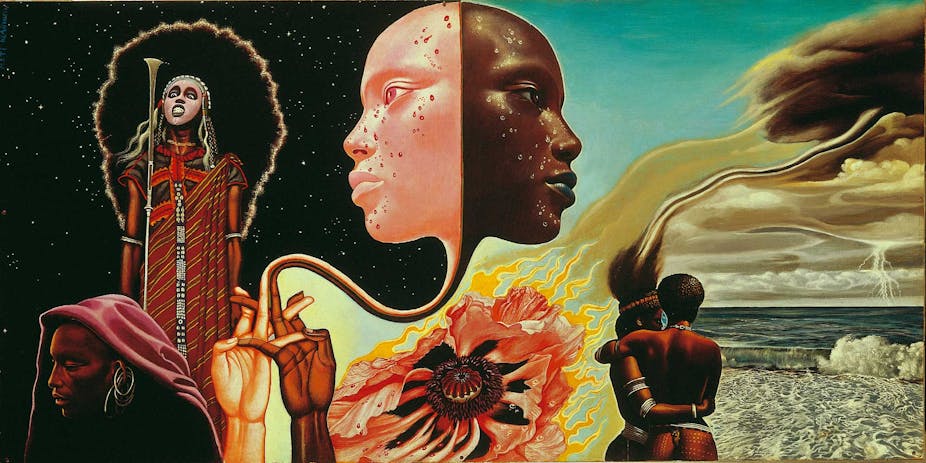

Then there was the album art, which was like something out of a fever-inspired hallucination or the guilt-ridden wet dream of a lonely German man (the artist Mati Klarwein was, of course, born in Germany). The whole package was important to me as it produced a challenge to think beyond aesthetics and form as I knew it and in a way much more complex than the commercial, pop diet that I was accustomed to.

My relationship with the records

A small disclaimer is in order: I was six years old when I first heard these albums. Besides hearing them being played, I often took liberties with my parent’s record collection and these were albums that I searched out as they fascinated me – because they confused me. Part of their collection included Alice Coltrane’s “Journey in Satchidananda” (1971), an album off which I used a track for a primary school science project (it was something about the solar system – I think I got a B+).

My experience with music at this stage was otherwise restricted to Michael Jackson. It was 1986 and I had a (pirated) copy of “Thriller” on tape, a leather jacket, a hat and one white glove. So, yes, I thought myself an expert on all things Jackson.

The comparison between Jackson and Davis is an unfair one. It’s like comparing a languid beach with the open ocean. One is warm and relaxing, luxurious and lazy with moments of excitement, energy and even eroticism. The other is spectacular, challenging, awe inspiring but unapproachable, inhospitable, terrifying and potentially destructive.

My terror as a six-year-old, in the face of Davis or Selim Sivad (as he incarnates back to front in “Live-Evil”) and his gang of conspirators was intense and insatiable …

I needed more … and over the years I sought out these two albums time and time again, re-listening to them as I grew up. I even went through a phase in my first year of university where I would buy a copy of “Bitches Brew” whenever I found one in a record shop – and for some reason in the late 90s I often found one. At one point I had four copies. All were lost over the years through break-ins or moments when I gave a copy away after a conversation that began, “You’ve never heard ‘Bitches Brew’!?”

Why is it still relevant today?

“Bitches Brew” and “Live-Evil” are more than albums. They are works: products of a combination of genius, depravity and bravery. While they are important to jazz and for music in general, for me the importance goes further than this musicological significance. “Live-Evil” and “Bitches Brew” are about meaning, interpretation and narrative – and the rupture of all of these categories.

They are a challenge to perception and a critical examination of the soul. They ask existential, metaphysical and dangerous questions. They dare you to go beyond the prepackaged/drive-through mode of consumption. They are a call to arms for the imagination and the spirit.

Birds of a feather

If you wanted to compare them to something, then “Bitches Brew” and “Live-Evil” would be the bastard children conceived in an orgy between Picasso’s “Guernica”, James Joyce’s “Ulysses” and Hunter S Thompson’s “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas”, while Aldous Huxley watched on and took notes. But that’s if you really had to compare them to something.

For me, the grooved wax discs and gatefold artwork that are “Bitches Brew” and “Live-Evil” are incomparable, as they are deeply rooted in the recesses of my subconscious. As such they are tightly bound to most things I do. I still routinely go back to them, and always find new marvels and wonders in the profane back-to-front mastery of Selim Sivad Evil.