Editor’s note: The following is a roundup of archival stories, and is an updated version of an article previously published Jan. 24, 2017.

Ajit Pai, President Trump’s chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, is a longtime foe of net neutrality. He has proposed completely repealing the Obama administration’s 2015 Open Internet Order, a decision the commission will likely vote to confirm on Dec. 14.

But what is net neutrality, this policy Pai has spent years criticizing? Here are some highlights of The Conversation’s coverage of the controversy around the concept of keeping the internet open:

1. Public interest versus private profit

The basic conflict is a result of the history of the internet, and the telecommunications industry more generally, writes internet law scholar Allen Hammond at Santa Clara University:

Like the telephone, broadcast and cable predecessors from which they evolved, the wire and mobile broadband networks that carry internet traffic travel over public property. The spectrum and land over which these broadband networks travel are known as rights of way. Congress allowed each network technology to be privately owned. However, the explicit arrangement has been that private owner access to the publicly owned spectrum and rights of way necessary to exploit the technology is exchanged for public access and speech rights.

The government is trying to balance competing interests in how the benefits of those network services. Should people have unfiltered access to any and all data services, or should some internet providers be allowed to charge a premium to let companies reach audiences more widely and more quickly?

2. Media is the basis of democracy

Pai’s move against net neutrality, media scholar Christopher Ali at the University of Virginia writes, is just part of a larger effort at the FCC to accelerate the deregulation trend of the past 30 years. The stakes are high:

Media is more than just our window on the world. It’s how we talk to each other, how we engage with our society and our government. Without a media environment that serves the public’s need to be informed, connected and involved, our democracy and our society will suffer….

If only a few wealthy companies control how Americans communicate with each other, it will be harder for people to talk among ourselves about the kind of society we want to build.

3. Pushing back against corporate control

Competition is already fairly limited, it turns out. Across America, most people have very little – if any – choice in who their internet provider is. Communication studies professor Amanda Lotz at the University of Michigan explains the concerns raised by a monopoly marketplace and the potential effects of turning back the current policy of net neutrality:

The rules were created out of concern internet service providers would reserve high-speed internet lanes for content providers who could pay for it, while relegating to slower speeds those that didn’t – or couldn’t, such as libraries, local governments and universities. Net neutrality is also important for innovation, because it protects small and start-up companies’ access to the massive online marketplace of internet users.

In this view, the internet is a public utility that should be preserved and protected for all to access freely.

4. Getting around the rules

Even with net neutrality rules in place, companies were pushing the boundaries of what is legal. In recent years, many mobile internet providers have been simultaneously imposing and creating exemptions from limits on how much data their customers can use in a given month. Called “zero rating policies,” these exemptions omit from the monthly cap certain types of data, or certain companies’ data. For example, T-Mobile customers can listen endlessly to Spotify internet radio regardless of how much high-speed data they use for other purposes. Information systems scholars Liangfei Qiu, Soohyun Cho and Subhajyoti Bandyopadhyay at the University of Florida examined the effects of those policies on the marketplace:

At first glance, zero rating plans would seem to be good for consumers because they allow users to consume traffic for free. But our research suggests the variety of content may be reduced, which in the long run harms consumers.

Their findings suggest that keeping the internet open would be best for the public.

5. Regulation isn’t always a good solution

However, regulating with that sort of goal could be risky because of the fast-changing nature of the internet, writes technology policy scholar Scott Wallsten at Georgetown:

Today’s business models may not be viable in the future. Net neutrality rules run counter to that reality by freezing in place a particular industry structure, making it difficult for firms to respond to underlying changes in technology and consumer demand over time.

6. A vestige of the 20th century

Whether net neutrality rises or falls, however, the debate will continue. The rules and frameworks the government uses to try to regulate the internet are long out of date, and were written to address a very different time, when landline telephone service was not yet ubiquitous. Boston University communication and law professor T. Barton Carter explained what the real solution is:

The laws governing the internet were written in the early 20th century, decades before the companies that dominate the internet like Google and YouTube even existed. The only solution is a complete rewrite of the 80-year-old Communications Act – unfortunately a fool’s errand in today’s Washington.

7. Can net neutrality even happen?

And maintaining net neutrality itself could be a major challenge, if not a fool’s errand, thanks to important technical details that could make the ideal impossible, writes University of Michigan computer scientist Harsha Madhyastha:

If one user is streaming video and another is backing up data to the cloud, should both of them have their data slowed down? Or would users’ collective experience be best if those watching videos were given priority? That would mean slightly slowing down the data backup, freeing up bandwidth to minimize video delays and keep the picture quality high.

8. Check for yourself

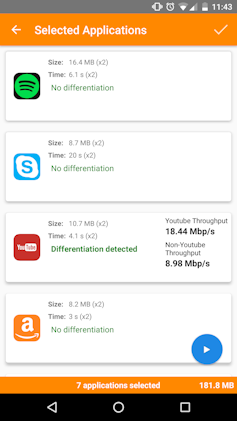

Northeastern University computer scientist David Choffnes describes how his team built an app that can measure exactly how internet service providers handle different types of traffic:

The methods we used and the tools we developed investigate how internet service providers manage your traffic and demonstrate how open the internet really is – or isn’t – as a result of evolving internet service plans, as well as political and regulatory changes. Regular people can explore their own services with our mobile app for Android, which is out now; an iOS version is coming soon.

Letting people see whether, and how, their data service handles internet traffic may be the best way to show people the importance of an open internet.

9. Very large stakes

If net neutrality is repealed, it could spell disaster for America’s position as an international leader in online innovation, writes global business scholar Bhaskar Chakravorti at Tufts:

Based on our findings, I believe that rolling back net neutrality rules will jeopardize the digital startup ecosystem that has created value for customers, wealth for investors and globally recognized leadership for American technology companies and entrepreneurs. The digital economy in the U.S. is already on the verge of stalling; failing to protect an open internet would further erode the United States’ digital competitiveness, making a troubling situation even worse.

10. Setting clearer guidelines

If Pai’s proposal goes through, it will signal that future changes in partisan control in Washington, D.C., could also lead to major shifts in internet regulation. A key part of this potential problem is lack of clarity in the laws, meaning regulators and courts have to sort through major policy questions that would better be dealt with in Congress, writes Timothy Brennan, a former chief economist at the FCC who is now a public policy scholar at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. He explains three steps Congress could take to simplify the debate – without even having to agree on the policy itself:

If Congress could enact legislation that removed the distinction between “telecommunication” and “information” services, reinforced the importance of the public interest in communications and restored antitrust enforcement power for regulators, the FCC would be better able to develop net neutrality regulations – whatever they may turn out to be – with solid substantive and legal foundations.

That could go a long way to furthering both public debate and public policy.