James Cook University drew a lot of attention in the higher education sector recently by publicly “opting out” of the Times Higher Education (THE) World University rankings. Their reason was simple enough – the rankings do not reflect a university’s true worth.

For much the same reasons, my university, the University of Southern Queensland (USQ), has never participated in the rankings. They have a clear bias against specialised, regional, English-speaking universities that cannot be ignored.

As the idea of what a university is changes, it could be that these rankings are holding education back - geared to a traditional model that asks only for conformity.

Diversify or perish

The university “brand” has been developed over some eight centuries. There have been many changes in that time, with much regional variation. For example, in the 19th century British universities were largely teaching institutions while German universities took leadership in research.

However, over the past sixty years, “brand university” has galvanised around a particular model characterised by a comprehensive coverage of disciplines, a heavy emphasis on research, prestigious flagship teaching programs in areas such as medicine, and highly selective entry requirements for students.

Today, the traditional university brand is so strong that when the word “university” is mentioned, the image that most people immediately think of is an elite, conservative, research-intensive higher education institution that is steeped in ancient academic tradition, aloof from its community.

A problem with this standardised notion of a university is that it runs counter to just about everything that is needed for the Australian university sector to prosper – both economically and in terms of its position in society.

The government has emphasised through the Bradley report that rather than having a sector consisting of 39 universities that are all the same, we should be striving for a diverse higher education sector. Universities need diversity just like business or industry does – to stimulate competition, to encourage innovation and to meet diverse needs.

But the power of brand university means there are consequences for institutions that choose to operate outside of this particular mould.

Damned if you do…

As a case in point, universities such as my own that pursue a mission that seeks to broaden educational participation by providing opportunities for non-traditional student groups are slammed from all quarters.

Rather than being praised for being able to bring often poorly prepared students up to graduation quality, or for building social capital in communities, these universities have to endure the stigma of poor performance ratings that are geared to the standard brand university model.

Most university ranking schemes place a heavy emphasis on accumulated research performance, which will naturally exalt research-intensive universities and gloss over the strong research performance in smaller universities.

However, even when measures of learning and teaching are considered, institutions departing from the brand university model still miss out.

Retention rates are a great example. The very act of enrolling from a diverse student constituency – including adults who are studying part-time with family and work responsibilities – while rigorously enforcing unforgiving graduation standards, means retention rates will be lower than traditional institutions.

Still, retention remains a proxy indicator for teaching quality and universities with lower retention rates are perceived accordingly.

We are still awaiting the development of a performance indicator that measures how much an institution’s learning and teaching program adds to a disadvantaged student’s performance.

Stagnant model

There is a view that has emerged from the rigidly hierarchical US higher education system that all universities are striving to become Ivy League institutions – that the ultimate aim is to live up to the “brand university” name.

The assumption then is that universities that are different from this model must be inferior institutions still on a developmental path. Nothing could be further from the truth.

My own university, for example, has a long and proud history of pursuing its own particular mission concerned with widening higher educational opportunity, producing career-ready graduates in the professions, working closely with business and industry and contributing to regional development. These are the things we are passionate about.

We have a job to do and a part to play – and we do what we do exceptionally well.

If the government is serious about supporting a diverse Australian higher education sector, it needs to do more to ensure that the individual strengths and contributions of universities of all types and persuasions are better understood, appreciated and acknowledged.

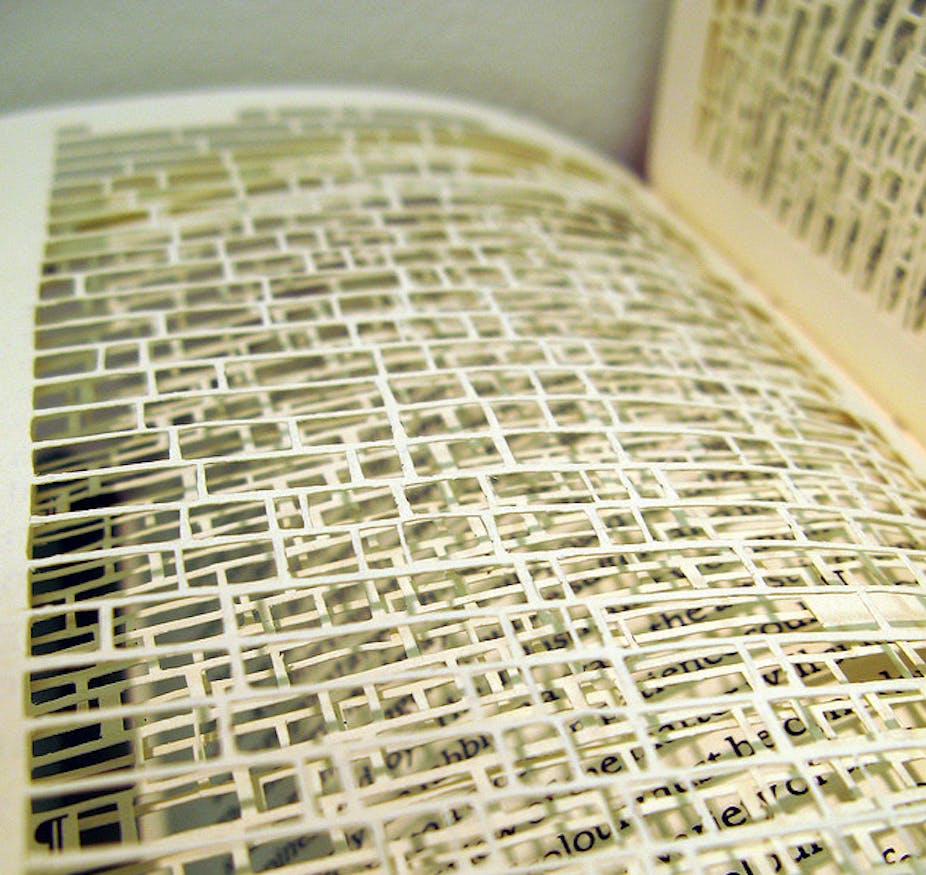

In Greek mythology, the bandit Procrustes would stretch and sever the limbs of his guests to fit the size of his bed. We, too, are continuing to stretch and shape our higher education to a particular standard to the detriment of students and society alike.