Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, who died on December 2 at age 94 from complications relating to Covid-19, came from a family of political notables and himself held – from generation to generation – many positions in France’s senior civil service and in parliament.

In the summer of 1944, young Valéry, a preparatory class student at Louis-le-Grand, participated in the liberation of Paris and joined the French First Army. In the autumn of 1945, he resumed his studies, first at the Ecole Polytechnique and then at the Ecole Nationale d'Administration.

Upon graduating in 1951, he joined the Inspectorate General of Finances. After a brief stint in the ministerial cabinet (as deputy director to ministerial council president Edgar Faure), he ran in the legislative elections of 1956. He was elected, at the age of 30, as deputy for the Puy-de-Dôme, a region with strong family roots for the young politician. He sat among the elected members of the Centre National des Indépendants et Paysans (CNIP), a right-wing conservative and liberal party without a particularly defined ideology.

He backed Charles de Gaulle’s return to power in 1958 and became secretary of state for finance in his government, working under Antoine Pinay, minister of finance and economic affairs. He himself became minister of finance and economic affairs in 1962. Giscard d'Estaing then founded the Independent Republicans, a group that grew out of the conservative group CNIP but which, unlike a large part of its elected representatives and the entire traditional political class, continued to support de Gaulle. Giscard d'Estaing was in favour of electing the president of the Republic via direct universal suffrage, which brought a new dimension to the Fifth Republic.

The road to the presidential election

Having pursued a policy of budgetary rigour that displeased part of the voting public, Giscard d'Estaing failed to secure reappointment in his ministerial role at the beginning of 1966. This freed him to pursue a strategy of “yes, but” in response to the Gaullist majority. He wanted institutions to become more liberal, and promoted a more modern and European-focused economic policy.

Through this attitude of critical support, he wanted to gradually strengthen the position of the Independent Republicans in order to shift the right-wing majority towards the centre. In 1969, when de Gaulle organised a referendum on the reform of the regions and the senate, Giscard d'Estaing advocated abstention or a no vote, which contributed to de Gaulle’s resignation. He returned to the Ministry of the Economy under the presidency of Georges Pompidou (1969-1974) but continued to push for his party to be more open to centrists.

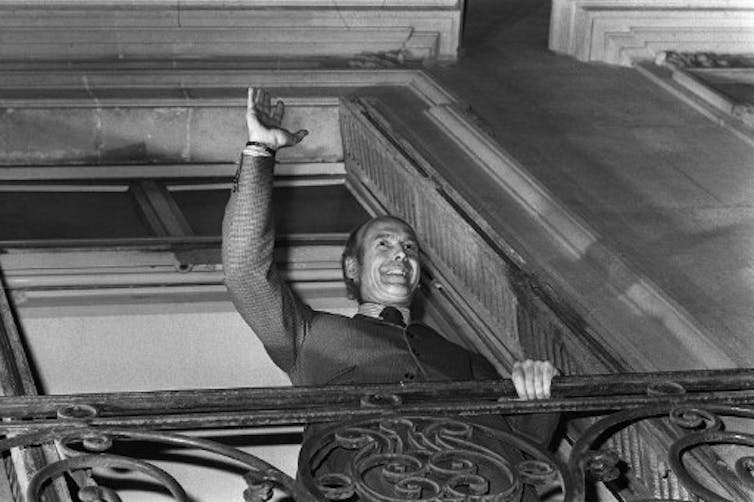

By the time of the 1974 presidential election, having strengthened his influence, he felt his time had come. He campaigned on the need for change, without the risks of the left’s agenda. He overshadowed Gaullist Jacques Chaban-Delmas in the first round and went on to win the second round in a very close race against François Mitterrand, becoming president at just 48 years of age.

The strategy first conceived of in 1962 to eat into the Gaullist majority and present a viable Independent Republican candidacy had finally paid off. Provisional support from Jacques Chirac and some of the Gaullists, who dropped their own candidate, helped make it a reality.

A seven-year term, reforms and an ‘advanced liberal society’

The beginning of Giscard d'Estaing’s seven-year term would be marked by numerous reforms. He wanted to symbolise change with a simpler and more relaxed style, which was reflected in the media coverage of meals with middle and working-class families.

For the first time, a Ministry of Women’s Affairs was established and several important societal reforms were initiated.

The age of majority, both electoral and civil, was lowered to 18, which is a way of recognising the importance of youth. Abortion was legalised, as was divorce by mutual consent. Contraceptives were to be reimbursed with social security. The city of Paris would have an elected mayor. The radio and television broadcasting monopoly was broken up into seven autonomous public companies. Giscard d'Estaing greatly increased – several times during his seven-year tenure – the minimum old-age pension. He stopped legal immigration but wanted to promote an integration policy led – for the first time – by a secretary of state for immigrant workers.

Giscard d'Estaing described his vision for an “advanced liberal society” in Démocratie Française (1976). He said the state must promote economic growth, serve the dynamism of economic actors and encourage major industrial investments in modernisation, such as the TGV or the nuclear industry.

According to him, the country was no longer divided between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat but increasingly dominated by the salaried middle classes. The government must respond to the aspirations of this large central group by developing individual liberties, promoting personal development and the quality of the living environment. It would be necessary to “govern from the centre”.

It was a decent enough goal, but from 1976 onwards, Giscard d'Estaing was faced with a deteriorating economic situation, high inflation and a spectacular rise in unemployment. The austerity plan put in place by Raymond Barre, prime minister and minister of economy and finance, introduced a temporary price freeze and a tax increase for the wealthiest. The president’s popularity suffered greatly from the economic turmoil.

At the same time, Giscard d'Estaing faced increasingly strong criticism from supporters of Chirac and from the left, whose union was faltering. However, he managed to retain a majority in the 1978 legislative elections and even strengthened the position of the centre and the liberal right, which worked together as the Union for French Democracy (UDF), a federation of parties that he launched on the eve of the elections.

European politics and the end of the presidential adventure

Internal debates were particularly intense when it came to Europe. Giscard d'Estaing had always been a strong supporter of the European project and, since his election, had acted to strengthen European governance by establishing the European Council, which brought together the heads of European governments, and by working towards a European monetary system.

He also supported the election of the European parliament by direct universal suffrage, which the Gaullists feared would lead to a supranational drift. His efforts were vindicated in a subsequent European election that delivered heavy losses for the Gaullists and opponents of European integration.

In addition to the economic difficulties that worsened at the end of his seven-year term (a second oil shock, steel crisis, ever-increasing unemployment, high inflation), there were also more personal challenges, mainly relating to the donation of diamonds by the Central African Emperor Bokassa, which later turned out to be of lesser value than first thought.

Hoping to secure a second term, he was once again pitted against François Mitterrand in the second round of a presidential election. This time he was defeated. He took losing to a hated leftist opposition badly and felt betrayed by certain Gaullist leaders who preferred to vote for the left-wing candidate. He ended up representing a brief intermission of centre-right liberalism after 23 years of the Gaullist Republic.

Rather than giving up politics, Giscard d'Estaing began to regain power from the local level. In 1982 he was elected general councillor of the Puy-de-Dôme in his fiefdom of Chamalières (where he had been mayor from 1967 to 1974), then in 1984 he again became deputy of this department, a mandate that he held until 2002 (interrupted by a stint as a member of the European Parliament between 1989 and 1994). He was also president of the Auvergne region from 1986 to 2004.

His return to politics also saw him produce a new essay: “Deux Français sur trois” (1984), which extended his 1976 manifesto. He described its purpose as “to conceive a national design reconciling generosity and efficiency and meeting the aspirations of two French people out of three. I want to serve the cause of a liberal and reconciled France”.

He gave up the idea of running again in the 1988 presidential election, judging his support to be insufficient, but he led several successful legislative and European election campaigns throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s. He considered running for president again in 1995 but gave up for the same reasons as in 1988. In 2000, while Chirac was in power, he led the charge in limiting presidential terms to five years.

European Referendum

In 2001, Giscard d'Estaing was chosen to lead a European commission charged with preparing a constitutional treaty for the union. He was at the centre of negotiations on the European constitution and then became actively involved in supporting the “yes” vote in the French referendum on the project. Although he was very much in favour of deepening European integration, he was reticent about the successive enlargements of the union, which, in his view, transformed its nature.

Defeated in the 2004 regional elections and no longer holding elective office, he would go on to sit on the Constitutional Council, of which he had been an ex-officio member since 1981 as former president of the Republic. This role obliged him to maintain a certain duty of reserve from which he emerged to support Nicolas Sarkozy in the 2007 presidential election rather than the centrist François Bayrou. He was elected to the Académie Française in 2004 and wrote several novels, which were not particularly well received by critics.

Valéry Giscard D'Estaing will remain the symbol of a political heir who knew how to shake up traditional France to kick start a liberal modernisation geared towards European integration.