May 8 2015 not only marks the end of an extraordinary general election and the beginning of the struggle for government. It is also the 70th anniversary of Victory in Europe Day (VE Day), and so is a day well used to times of change.

The occasion is being commemorated with three days of events across the UK. The plans include a parade, street parties, the lighting of beacons, a service of thanksgiving, and a “star-studded concert in central London”. The aim is to pay tribute to all those who contributed to the allied cause during World War II.

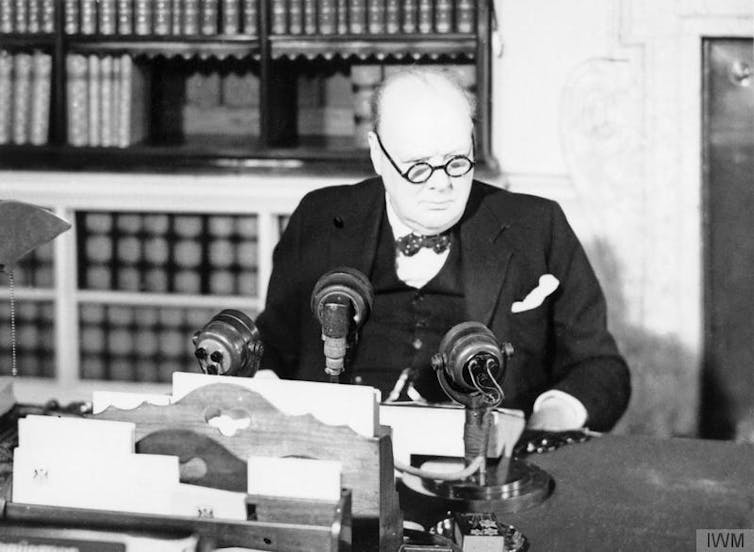

These events are designed to invoke the spirit of 1945. The street parties, bonfires and church services which marked the surrender of German forces have become a part of British national identity. The image of vast crowds gathered in central London to hear Winston Churchill announce victory is similarly ingrained. But those who experienced VE Day first hand are unlikely to recognise our contemporary re-imagining of them.

The idea of marking Germany’s surrender had been discussed by government since mid-April 1945. The celebrations held on May 8 were the result of careful deliberation between British, American and Russian authorities. But the events came after a week of frustrating rumour and were an anachronism to many who had lived through the war. VE Day failed to meet the expectations put upon it.

Delayed announcement

The surrender of German forces had long been expected. Newspaper headlines had forecast the end of the war for weeks. Reports of Adolf Hitler’s suicide had been released. But the lack of definite news caused frustration. According to reports from the time, “every anti-climax added a little to people’s slowly increasing apathy and frustration”. Some thought it was “a calculated policy to deflate people completely”.

The government’s decision not to announce the military surrender (which took place in the early morning of May 7 1945) hardly allayed popular scepticism. No official announcement was made until 20.30, by which time the news had been leaked to the press. The social research organisation Mass Observation reported that most of the people they interviewed felt that this had been badly mishandled.

There were spontaneous celebrations on May 7. The Daily Mirror reported that “London Had a Joy Night” as thousands of people amassed in the capital. In the words of its excited undercover reporter: “This is it – and we’re all going nuts!” But those who gathered outside Downing Street in the hope of seeing Churchill were left disappointed.

Although VE Day was designated a public holiday, very little else was officially organised. Tens of thousands again descended on central London, but there was no timetable so most simply drifted from place to place. The historian Correlli Barnett, who was in London on May 8, recently recalled people “aimlessly milling about in the streets like zombies”. The lack of catering facilities was a particular bugbear. And Mass Observation reported: “People seem unimpressed by official attempts to lend significance to the day.” The vast majority had simply stayed at home.

No sudden glory

The main reason why VE Day did not live up to the myth that now surrounds it was the nature of World War II. The day did not mark a sudden, glorious victory. Nor did it signify the end of fighting. The same Daily Mirror which reported “a glorious night” also reminded its readers of the war against Japan. There was “no peace, no holiday, no paper hats” for those in the Far East. This was a very different atmosphere to the end of World War I.

It’s clear that the festivities meant even less to those whose loved ones had been killed, or were being held in prisoner-of-war camps. More than 170,000 British troops had been taken prisoner in Europe alone. Thousands were still being held in the Far East. Many felt that the German surrender was not a time for abandoned rejoicing.

The future was equally daunting. The British public had been subjected to four-and-a-half years of devastating war. And it was not clear what peace would mean. There were questions about Europe. Britain’s relationships with the United States and Russia was already strained. And the news of Nazi atrocities was only just beginning to be released. One unnamed RAF Officer surely spoke for many when he feared that: “it’s going to be a phoney peace”. VE Day marked an end of certainty.

This was linked to other, more practical, reasons for the lack of enthusiasm. It was not just that plans for the day had been botched: Churchill’s coalition government was unable to offer a vision for the peace and bodies such as the wartime Ministry of Information – which might have been expected to organise the celebrations – were being wound down.

Mass Observation, which sought to give voice to the people, concluded that “VE behaviour” was “the product of many conflicting emotions”. Yes, people bought flags and held street parties. But they also felt scepticism, restlessness, guilt and fear. And we need to remember both when we commemorate the 70th anniversary of these events.