The rise of the vegetarian and, more recently, the vegan diet is generally perceived to be a new phenomenon. So, too, is their association with contemporary progressive ideas, politics and lifestyles. But plant-based diets have deep historical roots, and a longstanding connection with the political left.

From the time of the 1789 French revolution, when radical ideas were sweeping Europe, a political, ethical vegetarianism has grown alongside the British left. Advocated by major figures from the poet Percy Shelley to playwright George Bernard Shaw – as well as many more in pioneering leftist organisations and communities – contemporary writing demonstrates how a plant-based diet developed as an element of left-wing ideology, activism and identity.

Read more: Should veganism receive the same legal protection as a religion?

During the 1790s, several British radicals adopted vegetarianism as part of their broader attempts to overturn the existing orthodoxy. Influenced by philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s ideals regarding a “natural state” of freedom, peace and equality, people such as the Anglo-Jacobin revolutionary John Oswald, the radical scholar Joseph Ritson, and the publisher George Nicholson promoted the diet as a central element of their far-reaching arguments for justice and fellowship.

The diet had a significant presence in the Romantic period, especially within the circle of Percy and Mary Shelley. Percy Shelley wrote two essays advocating vegetarianism, one of which – A Vindication of Natural Diet (1813) – was appended to his influential revolutionary poem Queen Mab.

Queen Mab looked forward to a “paradise of peace”, a state of fellowship between all living beings, in which “man has lost / His terrible prerogative” to rob others of life. Depicting a simple, fulfilling existence led in harmony with nature, it illustrated a world “equal, unclassed, tribeless, and nationless”, devoid of needless conflict and division.

Ethics and ecology

Vegetarianism continued its association with the nascent left throughout the early to mid-19th century and became a common feature of socialism by the century’s close. Although largely grounded in ethics, arguments were also developed about its health and ecological benefits. These stressed the environmental burdens of meat production, and sought to counter a growing industrial-capitalist society of damaging over-consumption.

Read more: Going veggie would cut global food emissions by two thirds and save millions of lives – new study

Veganism was often acknowledged as the ideal, including by the fin-de-siècle socialist, humanitarian campaigner and pioneering animal rights advocate Henry Salt. Influenced by the ideas of Shelley, as well as the anarcho-communism of Peter Kropotkin and the evolutionary theories of Alfred Russell Wallace – both of whom stressed the importance of cooperation, as opposed to competition, in nature – Salt outlined a vegetarian-leftist outlook typical of the period.

Arguing that all forms of oppression were interconnected, he advocated “not this or that humane reform, but all of them” simultaneously, for it was not a single specific symptom, but the root “disease” – society’s underlying ethic – that required treatment.

Salt identified this as one of selfish exploitation, and so advocated a consistent principle of humaneness to oppose it, campaigning for the causes of socialism, women’s liberation, pacifism, vegetarianism and animal rights. All were, he asserted, “inseparably connected” and none could “be fully realised alone”. He thus promoted the extension of “compassion, love and justice” to “every living creature”, as part of a comprehensive ethical creed. He wrote:

I wholly disbelieve in the present established religion; but I have a very firm religious faith of my own – a Creed of Kinship, I call it – a belief that in years yet to come there will be a recognition of the brotherhood between man and man … when there will be no such barbarity as warfare, or the robbery of the poor by the rich, or the ill-usage of the lower animals by mankind.

He was not alone in outlining such a vegetarian–leftist vision. Edward Carpenter, the influential LGBT pioneer, shared a similar outlook, and many other significant figures likewise incorporated the diet into their broader politics.

Violence begets violence

Throughout this history, vegetarianism has been most associated with more holistic forms of leftist thought – those which look beyond economics to focus on the personal, moral and spiritual aspects of socialism. These “alternative” strands were particularly popular in the 19th century. Typically labelled “libertarian” or “ethical”, they emphasised the interconnection of individual and societal change, anti-authoritarianism and ideas of all-embracing liberation.

Many adopted the vegetarian diet because they recognised that violence towards other animals, and meat eating in particular, was part and parcel of the violent, exploitative society surrounding them. A society, as described by Salt, characterised by predatory consumption and wherein individuals, particularly the elite, became “almost literally cannibals … devouring the flesh and blood of the non-human animals so closely akin to us, and indirectly cannibals, as living by the sweat and toil of the classes who do the hard work of the world.”

In the view of Salt and others, meat eating habituated predatory behaviours and attitudes, eroded humanity’s benevolent instincts, and undermined the very basis of an ideal peaceful, cooperative society. To oppose meat eating was thus to challenge existing society, and to attempt to change its underlying ethic of exploitation and predation to one of compassion and cooperation.

What was needed was the widespread awakening of a new mindset: a “compassionate consciousness” which combined an instinctive sense of compassion and fellowship with a freethinking rationalist outlook. Through the cultivation of this active ethic of fellowship and love – both the means and ends of social advance – a new sense of universal kinship would naturally develop. To be vegetarian was to attempt to embody and progress a particular vision of the future by enacting it in everyday life.

A new way of being

Epitomising universal peace and fellowship, vegetarianism represented a new way of being. For this reason, its practice by key figures in the history of non-violence, from Percy Shelley to Leo Tolstoy and Mahatma Gandhi, comes as little surprise.

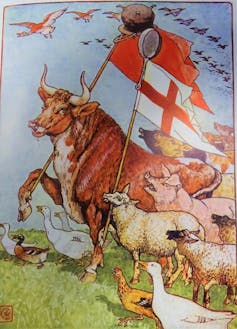

Equally, meat eating came to embody a counter-form of this ideology, with meat consumption frequently associated with masculine, militaristic and nationalist politics – as exemplified by the 19th-century symbolism surrounding John Bull, the patriotic beef-eating English everyman.

In this light, the diet’s particular adoption by numerous pioneer feminists and suffragettes, especially those who also identified as socialists, such as Charlotte Despard and Isabella Ford and, in the US, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, served not only as a rejection of the exploitative violence of an unjust social order, but of patriarchy itself.

Through the 20th century, vegetarianism’s association with the left continued, with numerous prominent Labour MPs, including Fenner Brockway and Tony Benn, practising the diet. And today, to knowingly mention Jeremy Corbyn’s vegetarianism is almost a cliche.

But now it is gaining ground among younger generations, too. Against the backdrop of the climate crisis, and with a growing appetite for a new politics of tolerance, compassion and cooperation, which seeks to demolish blinding barriers and divisions, vegetarianism and veganism appear increasingly relevant.