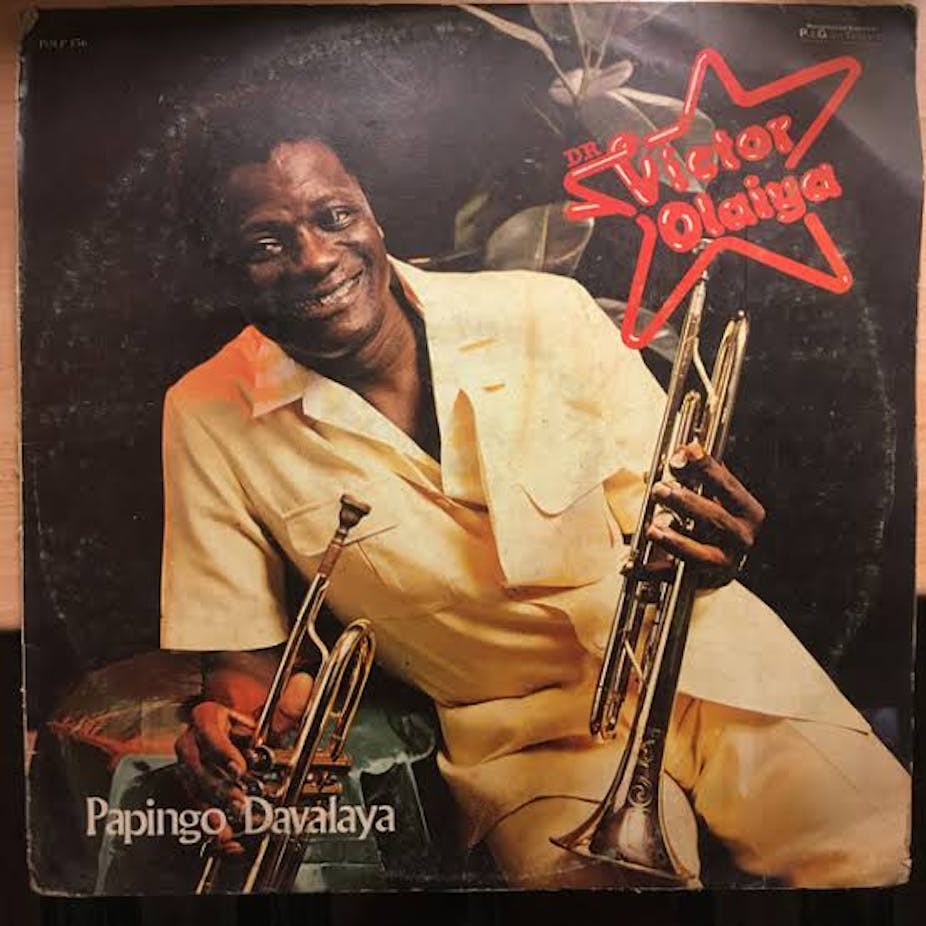

With Victor Olaiya’s death, an important chapter in the history of Nigeria’s popular music was closed. After 60 brilliant years as a bandleader, composer, and performer of highlife music, Olaiya passed away on 12 February 2020.

Olaiya helped to popularise highlife music globally. Together with musicians like E.T Mensah of Ghana and Nigeria’s Rex Lawson and Bobby Benson, he consolidated highlife music as a pan-regional genre with particularly strong roots in Ghana and Nigeria. Long after highlife had receded into relative obscurity, he refused to let go. Instead he created a niche space for it by presiding over weekly performances at his Stadium Hotel in Surulere, Lagos. His efforts made the space a vibrant spot for nostalgic performances that recall the social life of the country’s colonial era and the decade after.

Olaiya helped to professionalise musical practice in Nigeria. He was instrumental in the founding of the National Union of Musicians (NUM), the first government-recognised association of professional musicians in the country. He was a towering inspiration to many musicians, including Bala Miller, Victor Uwaifo, Rex Lawson and Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, all of whom played in his band before forming their ensembles.

Early years

Olaiya was born in 1929 in Calabar, Cross River State to Yoruba parents from Ìjès̩à-Is̩u, Èkìtì State. In 1947, he left for Lagos to begin a music career that would see him play with highlife masters like Samuel Akpabot and Bobby Benson. In 1956, He formed his group, Victor Olaiya and His Cool Cats Band. It was renamed All Stars Band in 1963.

Moving to Lagos helped him begin the process of gaining a deeper insight into his Yoruba roots. As he explained to me over multiple conversations, his music existed as an integral part of the larger cultural movement that anticipated and complemented the struggle for Nigeria’s political independence.

Not surprisingly, he and his art would become an important index of the euphoria and sense of optimism that marked the birth of an independent Nigeria. He performed at Nigeria’s independence celebration state banquet in October 1960. He also performed to Nigerian soldiers serving in the peace mission to resolve the Congo Crisis.

Olaiya’s unique performance of highlife is based on an intercultural profile. His music blends European tonal practices, Afro-Caribbean percussion and Nigerian melodies into a refreshing final product. Striking elements of his performance include his husky vocals, impressive trumpeting skills, and a warm persona. He sang in multiple Nigerian languages including Yoruba, Igbo, Efik, and Pidgin. His fanbase cuts across boundaries. Also significant is the multidimensional quality of his music: lyrical witticism (for example, in the song ‘Opataricious’), romantic ballad (Fàmí Mó᷂ra), which sometimes veers whimsically into indelicate text (Mo Fé᷂ Muyàn); folklore and riddles (Òrúkú Tindí Tindí), exhortation (Labalábá), and sheer captivating musical candor (O᷂mo᷂ Pupa).

Read more: Victor Olaiya: Nigeria's master trumpeter, gifted composer and genius showman

Social commentary

The weaving of social commentary with light-hearted entertainment is a recurring element of Olaiya’s music. This is exemplified in his immensely popular song, “Ìlú Le” (Times are hard; LP Polydor [Lagos] POLP 096, 1983). As shown in the title, the focus of the song is the harsh condition of life in Nigeria. Olaiya pays some attention to the vulnerable conditions of women in times of economic crisis.

The song employs relatively sparse instrumentation comprising of guitars and horns, and a light percussion made active through the clave pattern. The music has a laid-back tempo and employs multiple stanzas separated by modest instrumental improvisation. The song lasts for just over five minutes, following a typical Western pop form. It is remarkably different from the extended form of Juju and Afrobeat.

Olaiya’s handling of the topic of economic austerity is casual and non-committal. He proposes neither a solution nor asks difficult questions. Like many of his songs, this one is not formulated as a social critique. It is a simple reportage of the facts of social life. The sense of rhetoric aloofness that is conveyed in the song speaks to the distinctive differences between Olaiya’s music (indeed highlife music in general) and the more visible neo-traditional musical forms of the post-colonial era. His music does not aspire to the celebratory instincts of Yoruba Juju music. Neither does it lay a claim to the militant politics of Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat.

The differences marking these three musical idioms are ultimately reflective of the constantly changing political dynamics in Nigeria and how social conditions help to frame musical arguments. Olaiya’s music mediated the transition from colonial domination to national independence in mild terms. His approach is on par with the moderate politics of the Nigerian elite of the colonial era – the group that led the movement to independence.

And following the oil boom transformation of that elite into a wealthy, corrupt and conservative political class in the late-1970s, Juju musicians rose to cater to the interest of that new cohort. They rendered praise songs that massaged the ego of politicians, and smiled to the bank for it. Fela’s Afrobeat was forged as a radical counter-hegemonic musical project to fight corrupt and inept leaders.

Declining years

As the euphoria of national independence waned, the relevance of highlife music experienced a steady decline. By the early 1980s, it had become restricted to elderly social spaces. In western Nigeria Olaiya’s Stadium Hotel, like many such spots around the country, kept some of the flames alive. On select nights, they brought together committed highlife patrons who longed for oldies nostalgia.

Many highlife audiences that I interviewed when I visited the hotel in 2006 and 2016 explained that the nightclub helped them to reconnect with the melodic charm and ambience of highlife. Qualities they found wanting in many contemporary genres, especially rap music. It would seem that rap, in its exploration of new sonic territories, presents a radical aesthetic quality that challenges the conservative taste of the more traditional listeners.

Olaiya will be missed for his affable personality and resplendent performance style. The white handkerchief-waving trumpeter is no more, and his Stadium Hotel will now be very different from what it used to be.