The death of Warren Mitchell earlier this month received less publicity than might have been expected, given that for several decades he played one of the most famous fictional characters in British popular cultural history. But the man behind the monstrously iconic Alf Garnett died during the weekend of the appalling terror attacks in Paris – and his passing thus quite properly occupied a lower rung on news agendas.

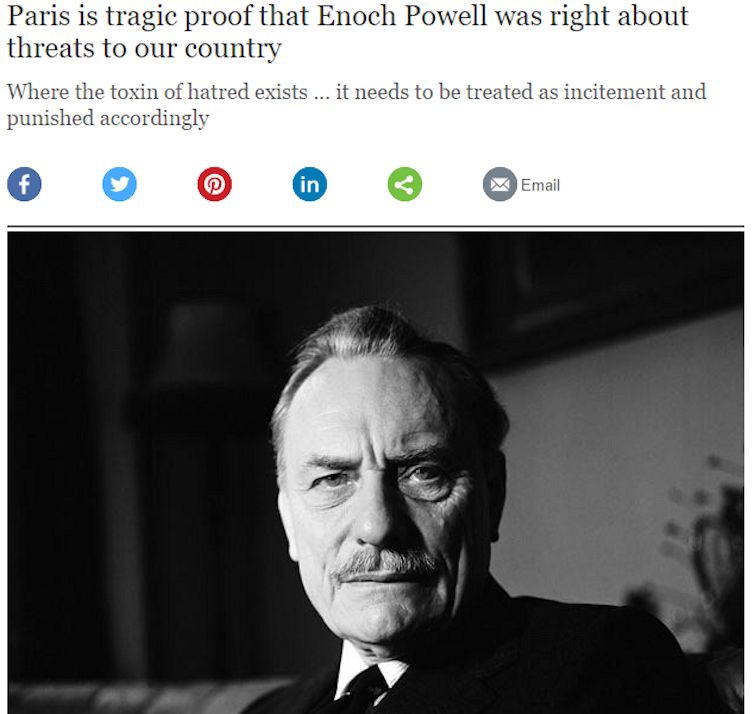

Perversely, however, the shade of the awful Alf has not been entirely absent in recent days, as media wrangling about the Paris events – and related atrocities from Beirut to Bamako – took strange turns in some quarters. One can almost set one’s alarm clock, whenever terrorism, immigration and integration are discussed in Britain, to ring when the first “Enoch Powell was right” piece appears – and the Telegraph ran an article last week by Simon Heffer, friend and biographer of Enoch Powell, advancing that claim.

Linking the real Enoch with the fictional Alf is not to propose a new connection. Although Garnett’s first TV appearances predated Powell’s inflammatory speech about immigration by some years, the longevity of the various Garnett franchises ensured that Powell’s name featured regularly in them, invoked in Alf’s tirades as a great man, ignored prophet and revered figurehead.

Powell was in turn lambasted by his critics as a Garnett-like figure, although (according to Heffer’s biography) he claimed not to know who the sitcom character actually was. And let us not forget, the first mass public support for Powell’s anti-immigrant views came from a protest march of East End dockers, who shared their geographical location and their line of work with Alf.

‘Scouse git’ and other slurs

The first series of Till Death Us Do Part, the BBC sitcom centred on the Garnett family, began in June 1966. Success and controversy were jointly immediate, the latter thanks to the prevalence of what was “bad language” for the time.

Television comedies at that time were not accustomed to throwing around words like “bloody” and “git” with such frequency, or indeed uttered with such envelope-pushing relish by the talented cast, chief among whom was Warren Mitchell, who lent to the domineering, loud-mouthed Alf an unvarnished authenticity rarely seen before on British TV.

The series author, Johnny Speight, drew on his own East End roots to deliver scripts which crackled with the flesh-and-blood vigour of working-class domestic tensions. Alf’s main antagonist in the show was his Liverpudlian son-in-law Mike (played by Tony Booth, Cherie’s father) the “randy Scouse git” – an insult that quickly achieved catchphrase status – who had married his daughter Rita (played by Una Stubbs). Matriarch of the show was Else, Alf’s wife, who said little as the two men repeatedly locked horns, but knew just how to puncture her husband’s inflated ego with perfectly-timed, withering put-downs.

Bigotry exposed

Speight always claimed, when those dismayed by the show’s seemingly indulgent highlighting of Alf’s reactionary views protested, that his aim was to expose the man as a foolish bigot. That aim is detectable even if you watch the series today, with Mike and Rita putting their Labour-voting views across to counter Alf’s Tory tirades, but unfortunately the textual power-dynamics are never equal, as Booth and Stubbs are no match for Mitchell in full rhetorical flow.

Mitchell, incidentally an Oxford and RADA-educated working-class Jew, acts them off the screen. So even though episode after episode crafts its narrative to show Alf as a bully, a windbag and a coward, the abiding memory of the series – both on its original screenings and in popular memory subsequently – hands him all the trump cards. Only Else’s undermining had any real impact, thanks to Dandy Nichols’ exquisite portrayal of the downtrodden but never defeated spouse.

Alf’s magnetism takes on its most disturbing dimension when he starts to expostulate on racial matters. Clashes in the early episodes centre on party political arguments, but as it moved into further series, with Alf’s rants clearly established as the main attraction, the net and the targets widened.

Alf had the full array of right-wing prejudices – pro-monarchy, anti-feminist, horrified by the Common Market, locked into a particularly Churchillian nostalgia for World War II – but nothing guaranteed outrage as assuredly as his racism.

If I feel brave enough to show any clips of the show to media history students today, they find it hard to believe that racist terms were aired so frequently. Alf’s racism was not confined to insults alone, it was rooted in a deep, visceral fear of contamination – he voiced concerns that letters posted by black or brown hands could infect other envelopes in pillar boxes and flinched with outrage on seeing a black man waiting in line with him at a blood donation centre.

Catalogue of hatreds

He was a one-man catalogue of hatreds, a repository of intolerable intolerance, yet he became televisually iconic, a hero to millions. The BBC celebrated Till Death as a programme which epitomised its 1960s drive towards cutting-edge culture (former director-general Sir Hugh Greene listed it among the series which “raised the BBC’s reputation to new heights”).

Pulling in the opposite direction, Mary Whitehouse, that exemplar of the twin-set Taliban who saw the BBC as undermining Christian family values, held the series up as a benchmark in degradation and filth – Johnny Speight, with wicked wit, made Whitehouse’s book Alf’s choice of reading for the outside lavatory. Series featuring Garnett ran, intermittently, all the way until Johnny Speight’s death in 1998.

The British appetite for Alf runs deep, it would seem. Warren Mitchell’s death brought the keyboard warriors out in force on to YouTube, appending to the clips and episodes featuring Garnett a predictable range of valedictory laments about how they embody a good old days now forbidden by (cue that laziest of phrases) political correctness.

Not far beneath the surface of those comments, and sometimes not beneath them is the anxious racism Garnett was designed to ridicule; it is an unsettling tribute to the compelling appallingness of Warren Mitchell’s star turn as the East End Enoch that the design still falters for many who watch, leaving Alf as their champion, a motor-mouthpiece who shouts prejudice loud and proud.