Review: Watt, Melbourne International Arts Festival.

It resembled a pot, it was almost a pot, but it was not a pot of which one could say, Pot, pot, and be comforted. It was in vain that it answered, with unexceptionable adequacy, all the purposes, and performed all the offices, of a pot, it was not a pot. And it was just this hairbreadth departure from the nature of a true pot that so excruciated Watt.

This passage from Watt, the novel Samuel Beckett wrote while hiding from the Gestapo during the second world war, describes the title character’s dawning certainty that a pot is not actually a pot. The instability goes beyond language to ontology, or the nature of being.

There is much to like in Barry McGovern’s adaptation of Watt, which presents selections from the text. McGovern is a seasoned performer who spoke Beckett’s repetitive prose beautifully. His quiet delivery brought out the novel’s deadpan qualities; the audience laughed often. And yet, I came away with the feeling that McGovern’s Watt was not quite a pot, which is to say, not quite Watt.

McGovern first adapted Watt for a production at Dublin’s Gate Theatre in 2010. In this Melbourne production, with his worn clothing, boots, braces, and pepper-coloured hat, he looked the part of a generic Beckett character.

This was not a bad thing per se, but it did contribute to my sense of seeing the ghost of a Beckett play. It is tempting to attribute this washed-out quality to the difficulty of adapting the novel to the stage. And yet, the problems instantiated by the novel’s narration are well suited to McGovern’s adaptation.

Beckett’s novel describes Watt’s journey to, within, and away from Mr Knott’s house, where Watt lives for some time as a servant. Upon leaving Mr Knott’s service, Watt travels to an institution, seemingly an asylum, where he tells his story to another inmate, Sam. But the story is told out of order, sometimes in unreadable language, and with fragmentary addenda appended by a fictional editor.

The narrator is not just unreliable, but impossible, or plural: though late in the novel the narrator identifies himself as Sam, who is reporting Watt’s story as Watt told it to him, neither Watt nor Sam were present at the beginning of the novel. These contradictions are not resolved; indeed, they constitute the novel.

McGovern sometimes was Watt while he narrated what happened to Watt. This was especially effective in two scenes. In the first, McGovern demonstrated the extraordinary way in which Watt walks:

Watt’s way of advancing due east, for example, was to turn his bust as far as possible towards the north and at the same time to fling out his right leg as far as possible towards the south, and then to turn his bust as far as possible towards the south and at the same time to fling out his left leg as far as possible towards the north.

McGovern spoke the lines while performing the motions, embodying Beckett’s comic repetition and the unexplained inefficiency with which Watt advances.

McGovern was likewise effective in a scene where Watt, resting in a ditch that anticipates the one in which Waiting for Godot’s Estragon sleeps, seems to hear “from afar, from without, yes, really it seemed from without, the voices, indifferent in quality, of a mixed choir.” A recorded choir sang the two verses Beckett supplies (though the music is not printed in all editions), including such lyrics as “Fifty two point two eight five seven one four” and “oh a bun a big fat bun.”

During the first choral verse I was unsure about the choice to include the recording, since it seemed to resolve definitely that the voices came “from without” — a point that Beckett leaves open. But as the second verse was sung, and as McGovern reacted with quiet but increasing perplexity to its nonsense, I changed my mind.

I was with Watt in that moment, but where was I? I could no longer say, in the world of the play, that the choir came from outside him; only that it seemed to, and that its lyrical improbability put pressure on this seeming. In moments such as these, McGovern enacted the instability of the novel’s form and perspective.

At other times McGovern spoke and performed as different figures from the story: as Arsene, the servant who leaves Mr Knott’s establishment as Watt arrives, or as a narrator (Sam in the novel, but nameless in the play) to whom Watt has told his story. Here too the shifts enacted the text’s instabilities in another medium. Who was speaking, and why were they telling us this story? We weren’t to know. In the audience’s laughter I felt an acceptance of skimming along the surface of things.

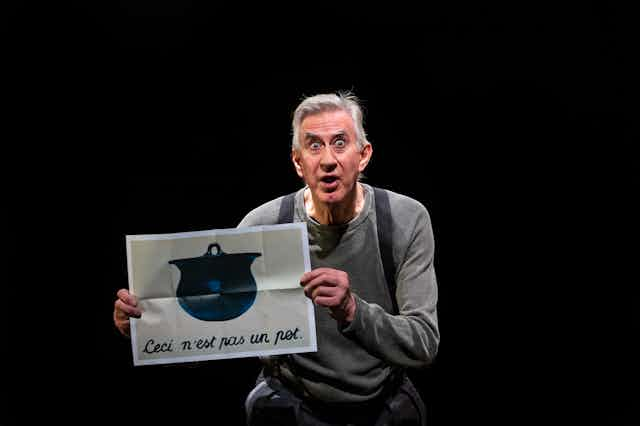

My dissatisfaction with McGovern’s Watt is not about what he included and excised, though one might object that he made it a bit too coherent. My frustration boils down to his treatment of the pot, one of the production’s few props. At the relevant moment, McGovern produced and unfolded a piece of paper with a picture of a pot on it. In so doing he made a point about representation: an image of a pot is not a pot. But I wanted him to make a point about existence — to produce a solid pot and make me question, or make me think he questioned, whether it was a pot.

Theatre is the perfect medium in which to make an audience see that a pot is not a pot. Stage pots may be real, may even be cooked in, but as props they are also fictional and fictionalizing. Making us feel this could have been a resonant counterpoint to the kinds of ghosting — Marvin Carlson’s term for theatrical elements that appear again and again — that attended McGovern, boots, braces, hat, and ditch.

Watt is being staged as part of the Melbourne International Arts Festival until October 13.