CHANGING FAMILIES: In this ten-part series, we examine some major changes in family and relationships, and how that might in turn reshape law, policy and our idea of ourselves.

We live in the golden age of housework, where robot vacuums can spend hours pirouetting around the living room. The problem is these labour-saving devices often amplify standards of cleanliness. Any time saved is spent on other household chores. And it’s no surprise who bears the brunt of this: women.

Take, for example, the transition from the hearth to the stove. This transformed cooking from one-pot meals to an elaborate endeavour of courses, all made possible by multiple-burner cooking and the stacking of a stove on top of an oven. Voilà, more work for mother.

The same goes for the washing machine, dishwasher, and the expansion of home sizes – more work for mother.

As a result, women are increasingly time pressed, stressed and depressed.

How much do men and women do?

Women today spend as much time doing housework as in the 1990s. Men have increased their housework contributions – a nod towards greater gender equality. Yet women still spend twice as much time on housework as men.

Full-time working Australian women spend, on average, 25 hours doing housework per week, including shopping for groceries and cooking. This is in addition to the average 36.4 hours full-time working women spend in employment.

Full-time working men spend an average of 15 hours doing housework per week, in addition to their 40 hours in paid labour.

When weighed together, full-time working women spend 6.4 hours more per week working inside and outside the home than full-time working men. Averaged across the year, this means a 332 additional hours (or two weeks of 24-hour days) of work.

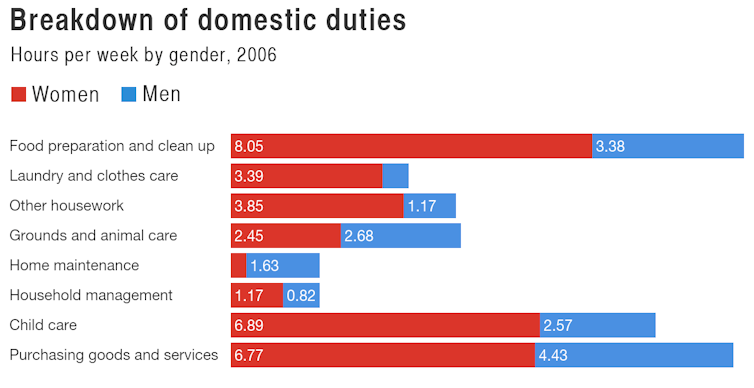

Women shoulder the time-intensive and routine tasks such as cooking, laundry and dishes. They’re also more likely to do the least enjoyable tasks like scrubbing the toilets versus washing the car. By contrast, men are more likely to do the episodic chores such as mowing the lawn or changing the light bulbs.

Data from the United States show a large and lasting gender gap. Women do more housework than men even when they are more educated, work full-time and are more egalitarian. In fact, some studies show women spend more time in housework even when their husbands earn less money or stay at home.

One argument for this counter-intuitive finding is that high-earning women do more housework as a way to neutralise the threat of their success on their husbands’ masculinity.

The jury is out on whether this claim is reliable but housework studies consistently confirm the symbolic gendered value of housework as a way to demonstrate femininity and masculinity in domestic partnerships. In fact, people’s sex lives are even tied to who does the dishes, with equal sharing couples having less sex.

Even Swedish women spend more time in housework than Swedish men, indicating that our Nordic sisters, supported by a system of equality, cannot get a fair shake on housework.

Emerging research is investigating housework allocations among same-sex partners for whom gender could be reduced or amplified. The results show same-sex partners are more likely to share housework than opposite-sex partners.

This suggests the cultural scripts associated with heterosexuality, marriage and family severely disadvantage women by holding them accountable for a larger share of the domestic labour.

It’s about more than just a clean home

Although performed in the domestic sphere, housework has important public consequences.

Women consistently spend more time in housework and, as a result, less time in employment. Recent estimates show Australian women account for two-thirds of the domestic load, while Australian men account for two-thirds of the paid work.

Women’s reduced attachment to the labour market means Australian families have less pooled family income, and women are more vulnerable to poverty if partnerships dissolve.

Income is consistently tied to power within relationships. So lower-earning women are less able to get their husbands to equally share in the domestic work. When women do earn more, their greater income is more likely to be directed to outsourcing housework than is men’s.

Moving towards domestic equality

One response to housework inequality could be to monetise domestic work and pay someone to complete it. This approach is currently being applied in Sweden where the government subsidises families for their outsourced domestic work. Through tax breaks, Swedish families are encouraged to hire maid services to help with the domestic load.

The Swedish government is betting the policy benefits will be two-fold. First, by encouraging women to more actively engage in the labour market. Second, to reduce the hiring of domestic labour off the black market, raising the wages, status and protection for women working in these domestic jobs.

With 38% of Australians intending to outsource some domestic labour in 2016, the demand for these types of services is large and growing, indicating a need to help families subsidise these demands and support the workers providing services.

State governments could play a role in implementing these services through tax incentives or direct services. This, in turn, could help protect the workers in these positions who are often disproportionately poor and of immigrant status.

A second response could be to stop penalising women for dirty homes. This requires a cultural shift in expectations of “good” womanhood to reduce the cultural pressure of domestic perfection.

Finally, bringing men into the cleaning process is essential. This means expecting men to be equal housework sharers and not helpers. It also means not penalising men for “not doing it right” when cleaning. Cleaning the house is a skill men can learn one toilet bowl at a time. And this is the key to reducing gender inequality in housework.

Read the other instalments in the Changing Families series here.