Australia is famous for its diverse and unique marsupials, and infamous for its world-leading rate of mammal extinctions.

In our latest research, we have added new names to the list of Australian marsupials – and at the same time, new entries to the grim catalogue of species driven to extinction since European colonisation.

Our new study, published in Alcheringa, has identified three previously unknown species of small carnivores called mulgaras, which live in the dry country of Australia’s west and north.

The species were “hiding” in museums, among specimens collected since the 19th century, and none of them survive today.

A deeper look at mulgaras

Mulgaras (Dasycercus) are small, ferocious carnivorous marsupials that are so well adapted to their arid habitats that they do not need to drink water. They play important roles in maintaining the health of their environments by controlling populations of insects and small rodents, and turning over desert soils through foraging.

Until recently, it was thought there were only two species of mulgara, the brush-tailed mulgara (D. blythi) and the crest-tailed mulgara (D. cristicauda).

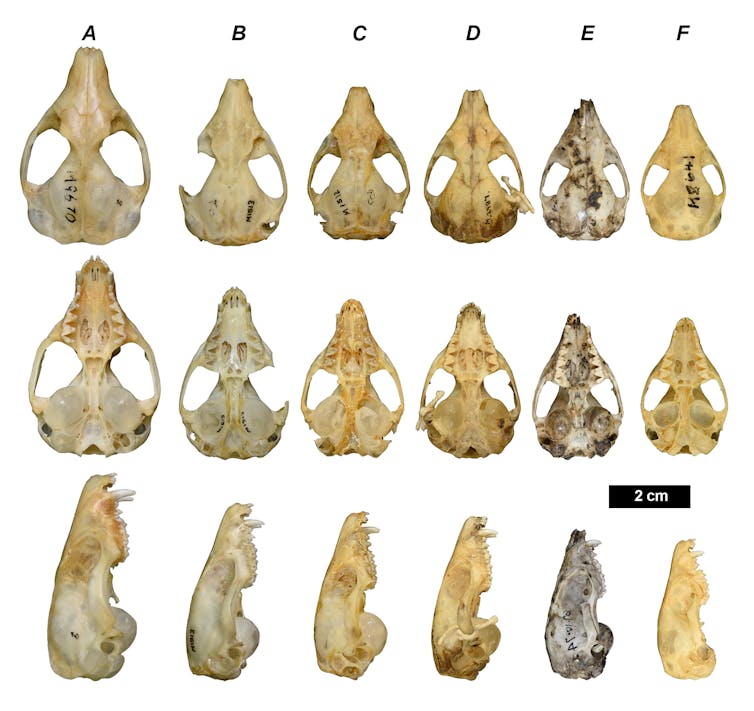

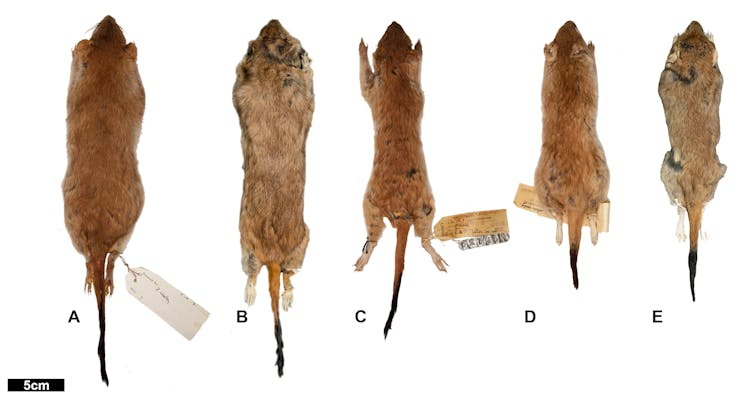

Earlier efforts to classify mulgaras focused on external differences, such as the hair on their tail or the number of nipples. Our new work looked deeper, through an analysis of skulls and teeth.

Mammals use their teeth for many things, most obviously as offensive or defensive weapons, for eating, and for manipulating the environment. If the shape of a species’ teeth changes in some way, this could indicate an adaptation to a change in diet or environment. With enough adaptions and changes, a new species emerges.

Read more: Explainer: what is biological classification?

In our investigation, we examined “subfossils” – skeletal remains that are not old enough to be true fossils – from sites around Australia where mulgaras are no longer found.

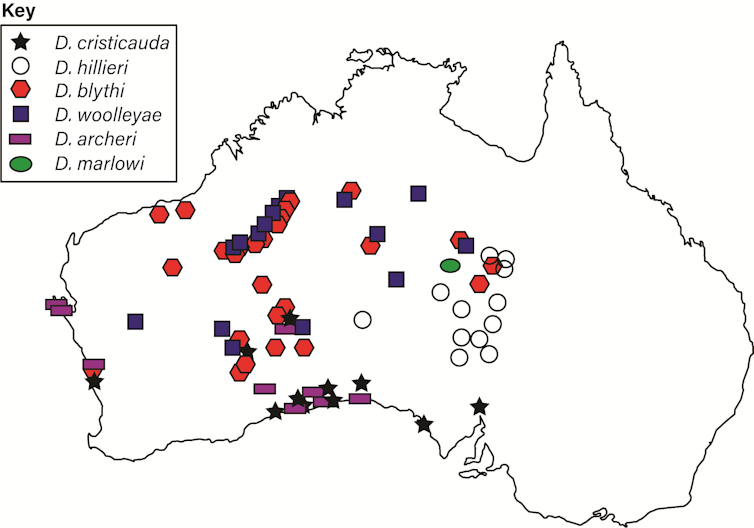

We trawled through animal trapping and subfossil collections made since the 19th century in museums across every mainland state and territory in Australia, and even the Natural History Museum of London. Subfossil specimens from the Nullarbor Plain, the Great Victoria Desert, and the northern Swan Coastal Plain were of particular interest as they had not been attributed to a particular species until now.

We also mounted an expedition to the caves of the Nullarbor Plain to collect additional mulgara skulls.

Not one, two or three species, but six

Once we had assembled our collection, we measured the skulls and teeth of the mulgaras to find differences in their overall shape and size. The particular diets and habitats of particular species are expected to leave distinct patterns in their skulls and teeth.

We found differences in the skulls and teeth of mulgaras that completely revised our understanding of their diversity and recent history. Our most remarkable discoveries were found in subfossil deposits that had previously not been classified.

Previously, researchers disagreed about whether there are one, two, or even three species of mulgara. We found a total of six species, living in different habitats across central and western Australia. Two of these were already accepted to exist, another had been proposed in the past but dismissed, and three were entirely new.

We also found that some of the external features previously proposed for identifying species of mulgara were actually shared by multiple species.

For instance, the brush-tailed mulgara (D. blythi) and the crest-tailed mulgara (D. cristicauda) were separated based on the shape of the hairs on the end of their tails. However, it now seems that four of the six mulgara species have crested tails, while the other two have brush tails.

Just as you cannot judge a book by its cover, you cannot judge the importance of a mulgara by its size, or its taxonomy by its tail!

Four modern extinctions

Our research is not all good news. Of the six mulgara species, we determined that four are already extinct, likely as a result of the introduction of foxes and cats to Australia.

The extinction of these mulgara species may represent the first extinction in modern Australia within the broader family of Dasyurid marsupials, which also includes quolls and Tasmanian devils.

These newly identified mulgara disappeared with even less recognition than the now infamous extinction of their marsupial relative the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger.

Read more: Extinct but not gone – the thylacine continues to fascinate us

These historical extinctions and lack of awareness exemplify the current ecological crisis facing Australian mammals.

Prior to our research, it was known that mulgaras are threatened and their population and distribution across Australia has decreased.

Our research shows these declines are far greater than we thought. It also shows the importance of using subfossil records to understand the relatively recent history of marsupials for conservation. To protect Australia’s ecosystems, we will need to invest in much broader taxonomic understanding.

Read more: The good, the bad and the ugly: research funding flows to big and beautiful mammals in Australia