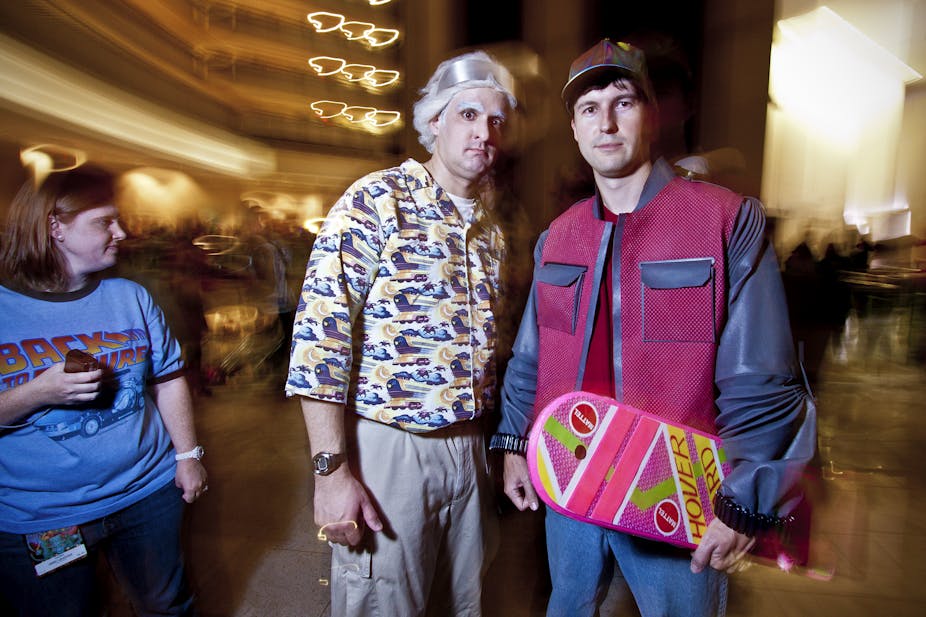

History is generally made of things that happen. This truth often prejudices us to ignore the importance of the things that don’t. In this spirit, I would like to bring attention to the significance of something that won’t be happening before the close of this year: we will not be getting hoverboards.

Many of us of course realise this is a reference to Back to the Future II (1989) which imagined that, by 2015, young people would be gliding across urban streets, sidewalks and parks (but not ponds) on boards floating six or so inches above the earth.

This is a seemingly banal technological disappointment but for those who lusted after such a toy in childhood after seeing BTTF II, it holds greater meaning than at first blush.

As children, although we still felt the disappointment at each bump in the sidewalk that came from skating on boards bound by gravity and supported by wheels; we thought that one day, by the then unbelievably old age of between 30 and 40, we would be able to coast across the world without the lubrication of snow or the evenness of smooth concrete.

Is this simply a small instance of experiencing the bruising realisation that much of the future never arrived? In a recent Baffler essay about technological advancement in the second half of the 20th century, the anthropologist David Graeber argued that such technological breakthroughs have failed to match expectations generated at the middle of the century.

Moreover, the majority of advancements have come only in the form of data processing and transmission and not the transformation of actual matter and physical processes. So now we are left with only the hollow enjoyment of the artifice of special effects about a future in which we very obviously do not live.

In the context of more serious aspirations about the future in films of the preceding decades, such as enlightenment and discovery through the peripatetic experience of space travel as presented in both the West’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Solaris (1972), the Soviet’s response to it, the absence of hoverboards may seem like not that big a deal.

But it’s worth noting that instead of hoverboarding by 2015, the exact opposite has happened – we now see Marty McFly’s 1980s-style skateboard everywhere in the hands of youth.

These retro skateboards with large neon wheels, tapered triangular heads and rear foot-guards are a regression in many ways. They bear no marks of the developments of skate technology or aesthetics that took place in the 1990s and 2000s.

How or why did such a thing happen? It seems part of a stylistic return to cultural forms of the 1980s but a return that can only understand that period cynically.

The present always had some combination of the past in it so the return of the 80s should not be a big surprise. Is this simply one generation playing with the cultural forms of the epoch just before their birth?

Much of the 1990s looked like the 1960s, with unkempt granola hair in a style that we call grunge. The 2000s had similar aesthetic qualities to the 1970s, seen in the hip-hugging jeans, large lapels and men’s poor choices in facial hair. Perhaps it’s just the 1980s turn to be recycled as a cultural assemblage.

I don’t think the story is that straightforward. The way in which we insist on reviving it tells us a great deal about our frustrations at the chafed borders of our imagination and reality.

The evidence for this is found throughout the numerous remakes of 80s’ movies and television that are popular today. Before the recent proliferation of such films, there were two antecedents for such a genre. That 70s Show (1998-2006) ostensibly parodied the culture of a particular decade. But this pretext quickly wore out and it became an inane teen sit-com and soap opera.

Ten years ago, a complete prototype for the film version of this drama set its gaze on Starsky and Hutch (1974-79), a TV crime drama. In the 2004 film by the same name, Owen Wilson and Ben Stiller play caricatures of the detective tandem with the backdrop of a time and place only used to heighten the absurdity of the narrative.

In the recent genre of remakes, or what would be better described as parodies, turning drama into comedy, the most commercially successful iteration was another crime drama series, 21 Jump Street (1987-91). Today, the idea that two young cops would infiltrate a high school to prevent crimes can no longer be taken seriously although the rise in school shootings overlaps with the increase in narcotics in schools of the 80s.

In its 2012 reboot, the cops, their detective skills and the motivation to seriously protect young people become little more than objects of derision.

Even films not based on the 1980s, have parodied themes about the decade. In Crazy, Stupid, Love (2011), after he bares his emotional emptiness through deconstructing his own pick-up moves, Ryan Gosling’s character admits to Emma Stone’s that he does “the lift” from Dirty Dancing (1987) as the final act of his disingenuous seductions.

The “lift” scene in Crazy, Stupid, Love is self-consciously contrived and effective only through the characters performing an empty ritualised “lift” in which they are protected by the shield of parody so that they can feel comfortable enough for actual authentic romantic connection.

Although the scene mimics the music, movement and sexiness of Johnny and Baby in Dirty Dancing, the hesitance and cynicism are the exact opposite of the vital energy that gave the original its spontaneous joy.

The most extreme parody of our revision of the 80s was the creation of an alter ego for one of the decade’s quintessential heroes. Angus MacGyver (Richard Dean Anderson) personified a technological and moral capacity of the late Cold War period (also the basis of Airwolf, 1984-86, and Knight Rider, 1982-1986). It is a position we are no longer confident enough in to reproduce other than through farce.

As the titular character in the series, MacGyver combined ordinary objects to create and do extraordinary things – a set of skills governed by an innocently unambiguous moral centre. In 2007, Will Forte’s first sketch of MacGruber ran on Saturday Night Live, and for several years we watched as MacGruber’s flaws, vanity, homophobia, racism, insecurity, and more, humorously prevented him from disarming explosive devices.

In the 2010 film of the same name, MacGruber is completely ineffectual. The guiding morality directing his behaviour is now based on petty insecurities, in his best moments, and cowardice in the rest. His most technically effective device involves placing a celery stick in his buttocks and prancing around naked to distract guards at an arms deal:

There are a few exceptions to viewing the 80s solely within the guise of parody. The 2010 remake of the A-Team is perhaps the mildest version of farce in the renaissance of this period. The original series (1983-1987) contained the same formula as MacGyver but the technical and social skills needed to bring about righteous action were formed by an aggregate of several individuals.

In the film, the characters with the most technical skills, Murdock and Baracus, are more often employed in comic relief than given actual potency in the mission’s objectives.

The only attempt to remake an 80s series without farce was a total failure. The new Knight Rider (2008) ran for one season while the original ran for four, and was in syndication for decades.

Currently, the only serious drama set in the 1980s is The Americans (2013-Present). The straightforwardness of the title hints only vaguely at the crux of the show, that the protagonists are two KGB spies operating in Northern Virginia. The inversion of the decade’s ethos is rather breathtaking.

Could we imagine a greater refutation of our values than the production of an American TV series from the perspective of an al-Qaida cell set in the 2000s? Such examples demonstrate the variety of our inability to take the 80s at face value.

And yet, in the era of 80s parodies, we seem to be at the height of imagining drama without farce in other 20th century decades. The 1960s provides a backdrop for reflecting on contemporary and dated issues in Mad Men (2007-Present). Other popular period pieces such as Downton Abbey and The Wonder Years (1988-93) (2010-Present) have taken chunks of the 20th century seriously as resources for expressing and understanding the human experience and its variations.

So why revive the ethos of the 80s only to terminate it through farce?

The answer, I think, lies in the demographics of the disappointed and desperately anxious. The groups who watch, create and drive this genre are largely between the ages of 20 and 40, which is a rather broad range of generations and communal experiences to be lassoed together.

The older members of this group can be easily understood as a brood seeking nostalgia laced with disappointment. Living in an unexciting future that feels pretty much like the past with the singular addition of being perpetually let down by the lack of hoverboards and technological efficacy has turned them against the heroes of their formative years.

Those too young to have directly experienced the 80s, but able to reproduce them ironically, are stepchildren of the same skewed technological development but their avenue to farce is slightly detoured.

The novelty of their formative years was a technological medium that allowed them to explore the intricacies of comments, likes/dislikes or what could be called the discernment of and by others (Facebook) and things (Pinterest).

Exploration of cyberspace has not yet yielded the refreshing humanism that Space Odyssey and Solaris connected to voyages of actual discovery in outer space. Instead, social media has realised a generation of what philosopher Marshall Mcluhan called “mass man” who experiences life as something “related to all other men simultaneously”.

Such a condition gives rise to an atmosphere of anxiety and a humanity only willing to self-consciously and tepidly relate to anything. Instead of a clash of generations, we witness two successive ones synthesise their start-of-the-century ennui in their parody of 80s’ culture.

The most famous quote about farce and history, often used by culture theorists who are themselves leading intellectual farces, comes to us from Marx:

history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce.

The insincere recycling of 80s cultural forms may better be described as a history that repeats itself when it has nowhere else to go.