Here are two opposing definitions of rape.

Rape: a violent, criminal act almost exclusively inflicted on women and girls by men. An ordeal of which the outcome is devastating, shaming, psychologically and socially destructive for victims and far too often deadly too. A despicable expression of male power. A dreadful word spoken with great bravery and much risk to one’s dignity and credibility.

Rape: something done by rapists. A ruinous accusation almost exclusively targeting men and boys. Sex gone just a little bit too far. An accusation resulting from miscommunication and mixed signalling between two responsible parties. A dreadful accusation that reduces men’s economic and social status to the level of criminal and/or social pariah regardless of culpability, and thus a despicable expression of female power. A mischievous and risqué word used in comedy routines to show some people that they probably should learn to relax more.

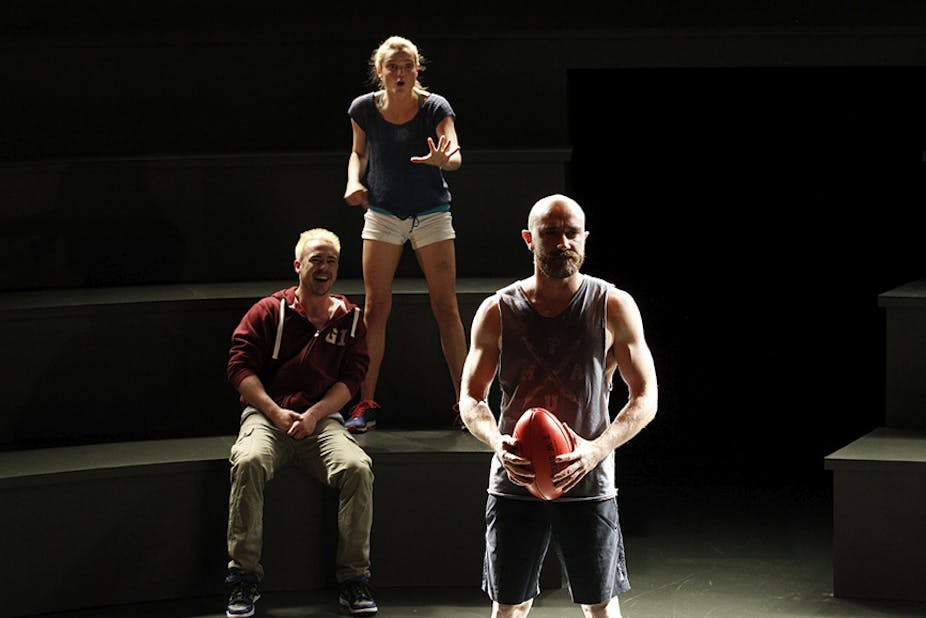

Last week a play called The Sublime opened at the Arts Centre in Melbourne, staged by the illustrious Melbourne Theatre Company (MTC). Written by Sydney playwright and actor Brendan Cowell, The Sublime has continued to draw criticism for its representation of rape in sport.

So much so that MTC felt the need to release a public relations statement clarifying the company’s position on the topic. But as theatre critic Byron Bache points out The Sublime has been criticised not because it condones sexual violence – but rather because of the wiggle room the playwright is trying to create around responsibility and victimhood in rape.

The playwright’s own words seem to support this argument. At the MTC season launch Cowell said The Sublime is:

about how a teenage girl with an iPhone can destroy not only a man’s life but entire power structures and industries who are the victims.

There are some pretty strong arguments as to why the words society uses to define the shared public good need to be clear, specific and unequivocal. Some words are specifically useful to our shared public good by being dreadful, ruinous or bordering on the unspeakable. “Rape” is one of those words. But the safer and more advanced a society perceives itself to be, the more resistant it becomes to the idea of dread, calamity or the unspeakable.

Take for instance Richard Dawkins’ recent attempt to grade different rape scenarios from bad to not quite so bad.

He, like Cowell, is – it appears – trying to purge rape of its irrational power. It seems an odd thing for a playwright to do, though hardly surprising of an arch-rationalist like Dawkins. Removing the magic of words has been one of the been a pet project of several Enlightenment thinkers – and those who still subscribe to its rationalist approach.

To Enlightenment thinkers words or language having inherent power was dangerously anti-modern. John Locke (1632-1704) believed that words were tied to mysticism, magic, and alchemy. Francis Bacon (1561-1626) argued that language should be reduced to a neutral scientific instrument; with the monarch as the arbiter of what was allowed or forbidden.

So distrustful of language were the Enlightenment thinkers that the founder of the Royal Society chose: Nullius in verba, “On no man’s word,” as its motto. But as Bauman and Briggs point out in Voices of Modernity: Language Ideologies and the Politics of Inequality, changing language on such a grand scale was a pipe dream.

That hasn’t stopped those uncomfortable or resentful of the power of dangerous words from attempting to renegotiate and diffuse their meaning.

Last week for instance, singer Ceelo Green tweeted some disturbing views on responsibility around rape and came out the worse for it.

Comedian Ricky Gervais opined on responsibility around stolen pictures of naked female celebrities and quickly found himself in a back-tracking spree.

In Australia, hip-hop artist Eso from Bliss n Eso is still waiting to find out whether Triple J will continue to play his music after his tweets around domestic violence.

Being as dreadful and important as it is, society can’t allow definitions around rape any kind of wiggle room. A very large, relatively independent section of Western society needs rape to mean something abhorrent, illegal and adamantly not the fault of its victim – either to confidently navigate their lived environment, or to have their loved ones be free to do so. A smaller, more niche group wishes rape to be more ambiguous.

Which brings us back to The Sublime.

While not condoning rape, Cowell has positioned himself in a very strange way. Playwrights — as opposed to rationalists and Enlightenment thinkers – depend upon the magical power of words for their works to affect audiences.

Playwrights don’t usually take the side of “entire power structures and industries,” either.

There are so many examples of playwrights speaking truth to power that it’s a stereotype, but here’s one that’s relevant. One of the first plays Greek tragedian Euripides (c.480-406BC) wrote was Medea and one of his last was The Bacchae.

Euripides was writing at the height of the Golden Era of Athens, and his work reflects his disapproval of his society’s arrogance and folly.

Medea deals with female rage and disempowerment and the terrible events that a man’s arrogance and opportunism brings about on his own family. Rather than blaming the victim, Euripides showed the conservative male audiences of Athens the consequences of their actions. The Bachae was written when Euripides was over 70 and a refugee from a besieged Athens.

The play deals with Euripides despair at the futility of Athenian society refusing to accept and acknowledge the darker, more irrational side of its own nature.

Two and a half thousand years later these are still important lessons.