This article contains explicit language.

Week after week, Dr Who gets himself and his companion, and often entire species, out of very sticky situations. With his trusty TARDIS and sonic sunnies, the Doctor inevitably finds the key to resolving the latest cosmic crisis he has stumbled on.

It can be a tough gig. But even in his current regeneration as a grumpy Scot, played by the alter ego of the most sweary character in the BBC’s history, you won’t hear the Doctor tell a dalek to “fuck off”.

As much as Peter Capaldi’s Doctor Who has an echo of the other famous doctor he has played – the spin doctor, Malcolm Tucker, from the award-winning series The Thick of It – and as hairy as it is being the Doctor, profanity is out of bounds.

To fans of The Thick of It, Tucker’s heart and soul was his foul mouth. The scriptwriters admit to using a swearing consultant who describes Tucker’s language as “high-octane baroque swearing”. But it is not gratuitous: it is an aesthetic dramatisation of the endless campaigning that characterises modern politics.

But what do we know about swearing by ordinary people?

Who uses the F-word, and how?

The world’s authority on the F-word is Lancaster University’s Tony McEnery. He is a “corpus linguist”. He uses banks of real language on a large scale to answer all kinds of questions about what language is like and how it is used.

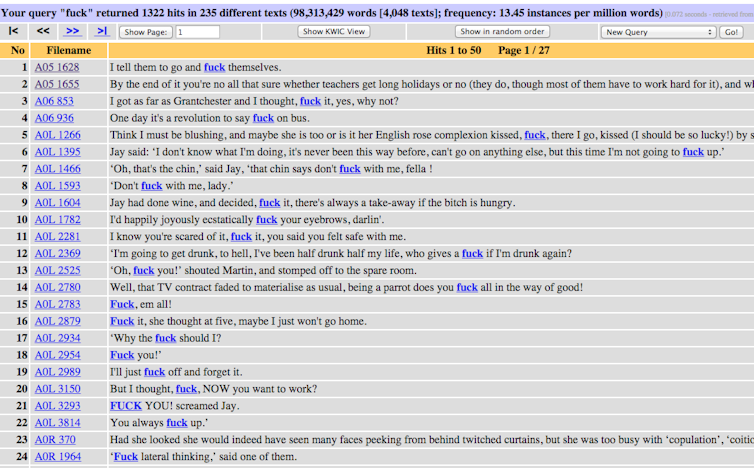

McEnery’s study of the F-word is based on the British National Corpus (BNC), a bank of 100 million words of British English collected in the latter part of the 20th century. Using the BNC, McEnery searched up the lexeme “fuck” and four associated forms (or “morphological variants”): “fucked”, “fucks”, “fucking” and “fucker(s)”.

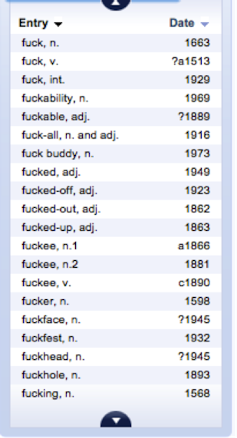

These forms, colourful as they are, by no means exhaust the extent of English speakers’ use of this word, as this list of related forms (below right) shows.

McEnery’s research shows the F-word to be more popular in men’s speech than in women’s, although when a broader range of swear words were investigated, there was no disparity between how often men and women swear. The F-word features more often in the talk of working-class people than of the middle or upper class, and is more common in the speech of the young than the old.

Overwhelming, the data showed that it was much more frequent in natural conversation than in forms of institutional talk, or in genres of writing.

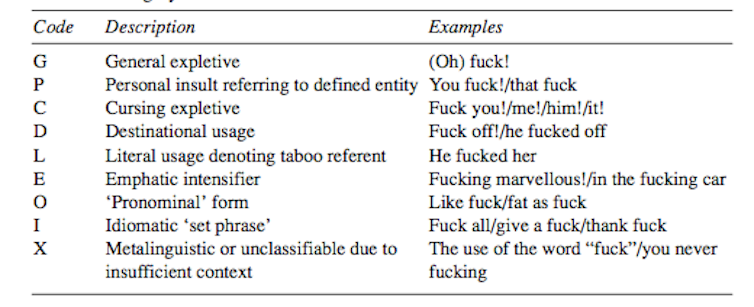

All swear words come from those aspects of human experience in which we invest our deepest emotions. McEnery’s research suggests the taboo meaning of “fuck” is not nearly as common as the use of the word as an “emphatic intensifier” – for example “fucking marvellous”, “in the fucking car” – or in the various idioms such as “fuck all” or “give a fuck”.

These usages, even when not strictly speaking tied up with the act of sex, draw their power from the taboo meaning.

Corpus resources in the UK and the US

The BNC is not the only corpus around, and is not the biggest. The Google Books corpus is more than 3600 times bigger. But it has no spoken language at all. The books selected all come from university libraries, largely in America. In corpus linguistics, size isn’t everything.

The linguists who put the BNC together knew a narrow set of parameters for data collection – no matter how big the samples – would not do the job they set out to do. They had had to collect a sizeable sample of spoken language, including samples of real human conversation, from the profane to the mundane.

They fashioned a sample of Brits from various regions, with due regard for age, gender and the class distinctions which the Brits so exquisitely observe. They gave their subjects a recording device to go forth and record themselves going about their lives. There is nothing comparable in modern corpus linguistics.

American linguists have some nice big corpora to play with. Brigham Young University’s Mark Davies has a freely accessible corpus suite, which includes a corpus of contemporary American English, of historical American English and of nearly 100 years of Time Magazine.

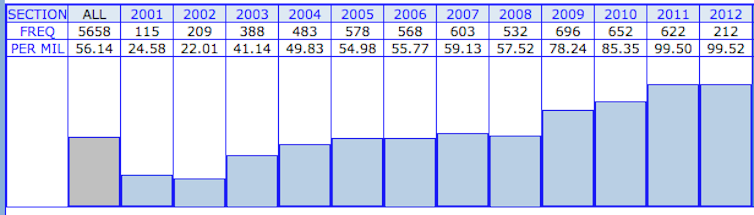

There is also a corpus of 12 years’ worth of American soap opera. It’s no good for studying the F-word, which in this 100 million words of soap opera dialogue does not turn up even once. “Bitch”, on the other hand, turns up at an overall frequency of 56 per million words. Its frequency is on the rise, at nearly 100 per million in the samples from 2011 and 2012.

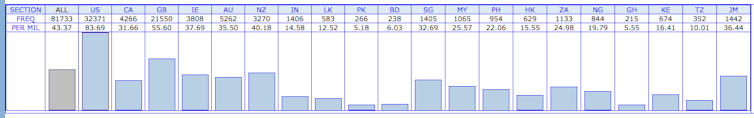

Davies’ website also hosts the GloWbe corpus, a random sample of web English from blogs, online newspapers/magazines and company websites, across 20 countries, collected in late 2012. My search of the word “fuck” (and its morphological variants) suggests Australians would not make the podium in a swearing Olympics. Gold would go to the US, silver to the UK. And bronze to the effing Kiwis.

Despite the significance and size of these corpus resources, the everyday speech of Americans is still largely dark matter.

Meanwhile, BNC researchers are currently updating their spoken data, paying ordinary Brits to record themselves in their natural linguistic habitats.

Australia lagging behind

Australia has nothing even within cooee of the BNC. There is an umbrella organisation, the Australian National Corpus, and plans for a publicly available corpus of Australian Indigenous languages. But Australian corpus linguistics lacks infrastructure.

While linguistic researchers continue to collect and analyse niche corpora, as do scholars increasingly in other fields of the social sciences, Australia has no standards for archiving, collating and sharing data – and no serious funding to develop its own version of the British National Corpus.

More’s the pity. American linguist B.L. Whorf described language as “an especially cohesive aggregate of cultural phenomena”. It defines our species.

Corpus linguistics data and techniques underpin empirical, evidence-based research in language studies. Without good data, how can we properly study and understand the currents of culture and meaning in and through which we live?