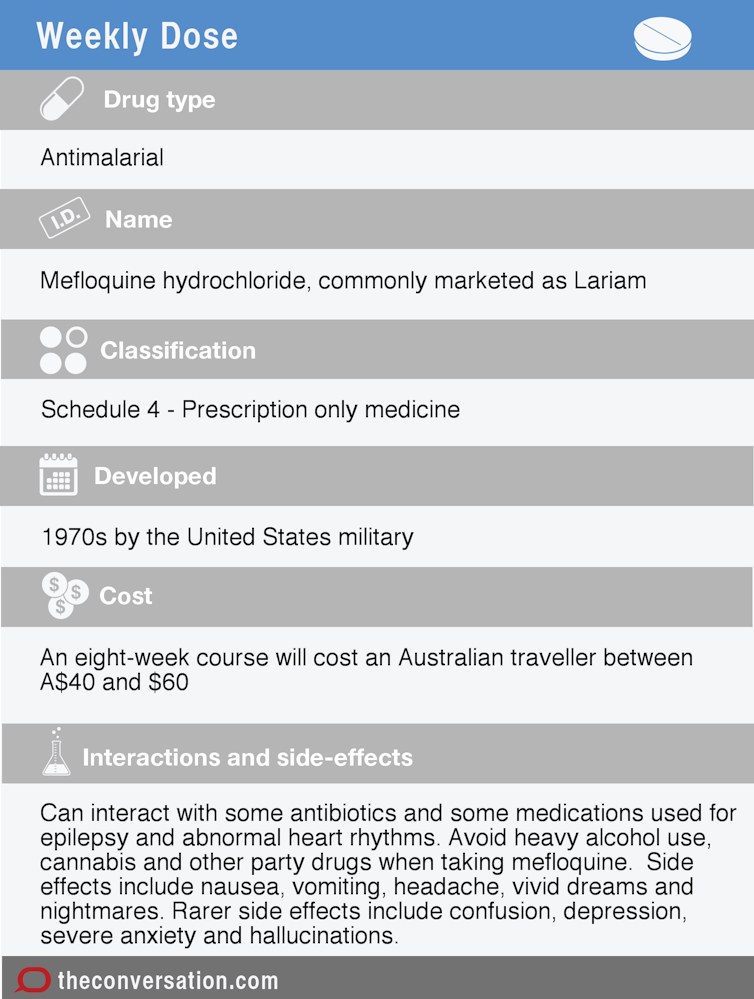

Mefloquine, mainly sold as Lariam, is used to treat or prevent malaria – a parasitic illness transmitted by mosquitoes in tropical regions. Despite significant reductions, malaria causes more than 200 million cases of illness and more than 400,000 deaths worldwide every year.

History

Mefloquine was one of around 250,000 chemical compounds tested for malaria-killing activity in the 1960s by the United States military, with a strategic imperative: protecting troops from malaria in the tropics.

These types of drugs had a military advantage. The use of preventive medicines by Allied forces in the Pacific during the second world war was considered a decisive factor in their victory over Japan.

The drugs that preceded mefloquine were prone to unpleasant side effects and malaria parasites in Southeast Asia had developed resistance to them by the 1960s. Alternatives were urgently needed to protect troops fighting wars in Indo-China.

Mefloquine’s discovery and development by the US army in the 1970s coincided nicely with its involvement in Vietnam.

After the Vietnam War, development was transferred to the pharmaceutical industry. Following animal tests and clinical trials in humans to help define dosing, mefloquine was registered by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 1989.

How it works

Mefloquine is a synthetic compound but its chemical structure is based on one of the first malaria drugs, quinine, that comes from the bark of South America’s Cinchona tree.

It’s not certain, but mefloquine likely kills malaria parasites by targeting specific metabolic processes that exist only in the parasite and not in humans.

For preventative use, drug levels maintained in the bloodstream over time are sufficient to kill the small numbers of parasites in very early stages of infection, before they have the chance to multiply and make a person ill.

To treat an already infected person, higher doses are used to kill larger parasite numbers.

How it’s used now

Mefloquine comes in tablet form. It is one of three drugs available (the other two being doxycycline and Malarone) for malaria prevention in travellers and those with occupations that put them at risk of malaria, such as military personnel.

The Australian military now describes mefloquine as a “third-line” drug for malaria prevention, meaning it should only be used by those unable to take doxycycline or Malarone.

For prevention, mefloquine is taken once a week (unlike other drugs that require daily dosing). It’s recommended mefloquine be started two weeks before travel and continued for a further four weeks on return.

For someone already ill, it is given once a day for three days, preferably in combination with a new malaria drug (the artemisinin derivative, artesunate) that has been highly effective in driving down global illness. The combination is less susceptible to parasite resistance.

Who uses mefloquine

Globally, an estimated 35 million people have been treated with mefloquine in some form. Now they mostly get the mefloquine and artesunate combination in malaria-endemic countries, especially in Southeast Asia and South America.

In Australia, doctors issue around 17,000 scripts per year for mefloquine, although use has recently been limited by concerns of side effects and availability of alternative drugs.

Side effects

Known side effects range from mild and common symptoms to rare cases of severe and even life-threatening events.

Milder symptoms include nausea, vomiting, headache, cough, vivid dreams and nightmares, feelings of restlessness and dizziness.

Well-known serious side effects are those described as neuropsychiatric. They can include confusion, depression and severe anxiety and psychotic symptoms, including hallucinations and bizarre behaviour. People at highest risk of these include those with pre-existing mental illness, epilepsy and some types of heart disease.

Symptoms that result in hospitalisation are thought to occur in about one in 10,000 people treated with mefloquine. In very rare cases, they have resulted in suicide or symptoms that persisted for many years.

The decision on whether or not to take mefloquine for malaria prevention must consider side effect risks as well as the benefits of avoiding serious illness. This should include a careful assessment of how much a given person’s travel plans put them at risk of acquiring malaria and the risks of side-effects from alternative drugs.

Additional considerations may include cost and convenience (some prefer mefloquine’s weekly dosing).

How much it costs

An Australian travelling to a malaria endemic area for two weeks would need an eight-week course of malaria prevention (including two weeks pre- and four weeks post-travel) at a cost of A$40-A$60.

Drug interactions

Interactions may occur with some antibiotics and with drugs used to treat epilepsy or abnormal heart rhythms that could respectively increase risk of seizures and palpitations.

Heavy alcohol use, cannabis and other “party drugs” with mefloquine greatly increase the risk of neurological and psychiatric side effects.

Controversies

In February 2016, it was reported that mefloquine was the only malarial treatment offered to asylum seekers on Australia’s Manus Island offshore detention facility. This was considered controversial as asylum seekers escaping often traumatic situations are a vulnerable group that may fit into the category of those with pre-existing mental illness.

The Australian Defence Force (ADF) is also embroiled in a high-profile controversy related to a mefloquine clinical trial conducted in personnel deployed in East Timor in 2001-2002. Some ex-personnel have claimed up to 30% of those who took mefloquine now suffer disabling physical and psychological symptoms including dizziness, vertigo, anxiety, panic attacks and depression.

Although these have been linked with mefloquine, evidence suggests it is uncommon for them to be this severe, and rarer still to persist for more than a few weeks after the drug is taken.

An investigation is also underway to determine whether the ADF employed adequate diligence and oversight in its prescribing practice over this time.

The guiding principle when prescribing mefloquine must be that patients are in a position to make a fully informed, autonomous decision about taking this drug, based on accurate information about its risks and benefits.