In Another Heart and Other Pulses, Michael Foot reflected on Labour’s traumatic 1983 election defeat. He struggled to relate the devastating result with his experience of the campaign. Enthusiastic crowds greeted the Labour leader wherever he went, creating a chasm between his expectations and the outcome.

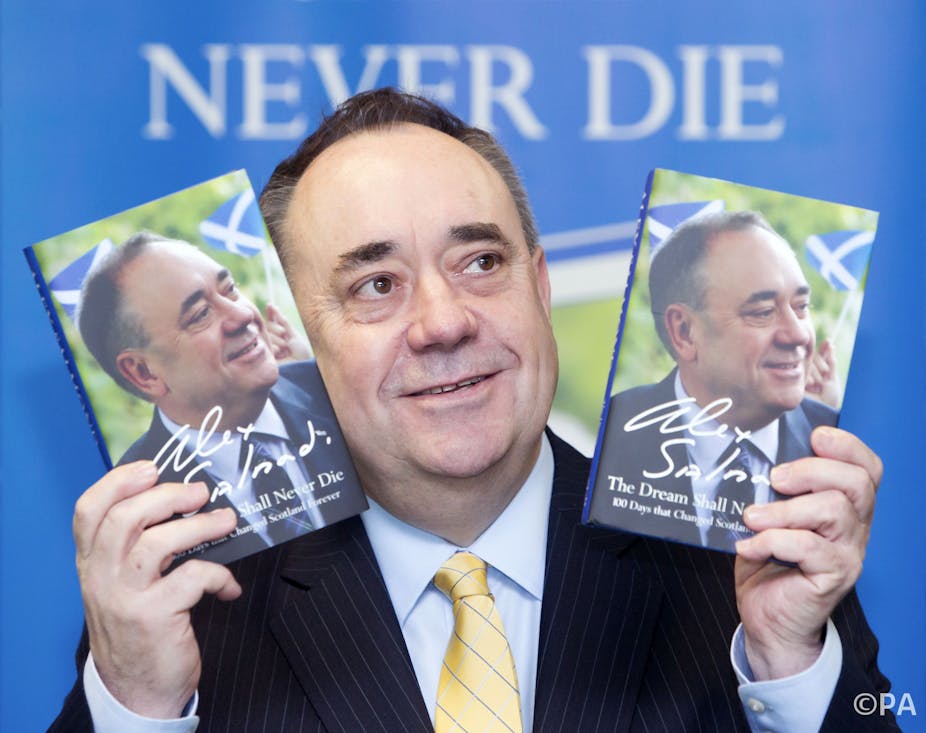

There is an element of this in The Dream Shall Never Die, Alex Salmond’s diary of the Scottish independence referendum – but only an element. Salmond experienced the enthusiastic crowds but his optimism was often forced and tactical –nobody wins who does not publicly believe they can win.

The key to understanding Alex Salmond’s attitude to the referendum is encapsulated in an entry on the day of the vote. It quotes James Graham, first marquis of Montrose, as one of his father’s favourite poems:

He either fears his fate too much,

Or his deserts are small,

That puts it not unto the touch

To win or lose it all.

Salmond has quoted those words at various key moments in his political career, and their significance tends to be overlooked. Often portrayed as a gambler, this is a man who has the courage of his convictions but has never doubted the scale of the challenge.

The Salmond enigma

The book gives insight into a politician who remains an enigma to many commentators, but only a little. The central role played by special advisers Kevin Pringle and Geoff Aberdein has been well known to close followers of Scottish politics, but the nature of these relationships becomes clearer from these diaries.

They also reveal the importance of his north-east base, which comes up time and again. It is a reminder that much Scottish political commentary is remarkably parochial. London-centricity has its Scottish equivalent in a central-belt-centricity that results in extraordinary blind spots among the commentariat.

Nobody with the slightest knowledge of the man would have taken seriously the notion that he might have stood against Danny Alexander in the forthcoming general election, for example. That is obvious from these diaries. Without understanding the politics of north-east Scotland, you won’t understand Salmond.

On the referendum, he makes clear that the UK government’s insistence that it was not planning for a Yes victory was not entirely true. He makes reference to an agreed position between the two governments on a text that was to be released in the event of a Yes vote.

The notion that the UK government would agree to this but not prepare for other eventualities is simply incredible – especially as there must have been a fear that the SNP would leak the agreement. It is ironic that it should be Salmond who reveals that Whitehall civil servants were engaged in the proper business of government and not just playing politics.

Colleagues and opponents

Some of the most interesting parts of the diaries relate to events before the referendum. Salmond reveals that Nicola Sturgeon requested 24 hours to consider his proposal that she stand aside to allow him to stand for party leader in 2004.

She thought he was annoyed that she had not immediately agreed but he insists that he admired her request. This is the closest thing to a split in the most formidable political partnership Scotland has witnessed in recent times.

On the subject of his opponents, the diaries reveal far more subtlety than might be expected here – even though Salmond has been fairly open in the past about his respect, even admiration, for many of them.

This book makes clear his contempt for the prime minister, but not for Alistair Darling, for instance. He clearly admires a man who reluctantly stepped up to the plate when an easy and lucrative life on the lecture circuit beckoned. What emerges is a politician who admires the characteristics that most define himself.

This admiration for those willing to put themselves on the front line might also provide an insight into a hallmark of Salmond’s premiership: loyalty to colleagues. Very few ministers were removed during his reign, while he brought some into his inner circle with whom he had had serious differences in the past – education secretary Mike Russell for example.

The boundaries of the possible

Generosity aside, there are some old scores to be settled. Salmond gives his version of the story of how BP intervened in the release of Lockerbie bomber Abdelbaset Ali Al-Megrahi, the Scottish government’s most controversial decision during Salmond’s period as first minister.

Salmond confirms the indications in the UK cabinet office review in 2011 that BP’s intervention to protect oil contracts led to the UK government being unwilling to exclude Megrahi from the prisoner transfer agreement between the two countries. “BP lobbied and the UK government jumped,” writes Salmond.

Much of the book focuses on everyday government business, which may surprise those who think Salmond spends all his waking hours plotting a route to independence. He uses public office very effectively as a pulpit when formal powers are lacking, such as his intervention in the shambolic mess that came close to closing Grangemouth oil refinery in central Scotland.

In general, this book has been written with a view to the future rather than the past. It may have taken most by surprise when Salmond resigned as SNP leader and first minister – but everyone should have realised he would have a plan B.

As Salmond looks increasingly likely to be among a large contingent of new Scottish nationalist MPs to Westminster in May, the reception that this book has received in some quarters makes plain that opponents still fear him. We will still have to wait until his political career is over before we get a fuller account of the events surrounding the referendum – but these diaries are more interesting and revealing than most expected or will admit.