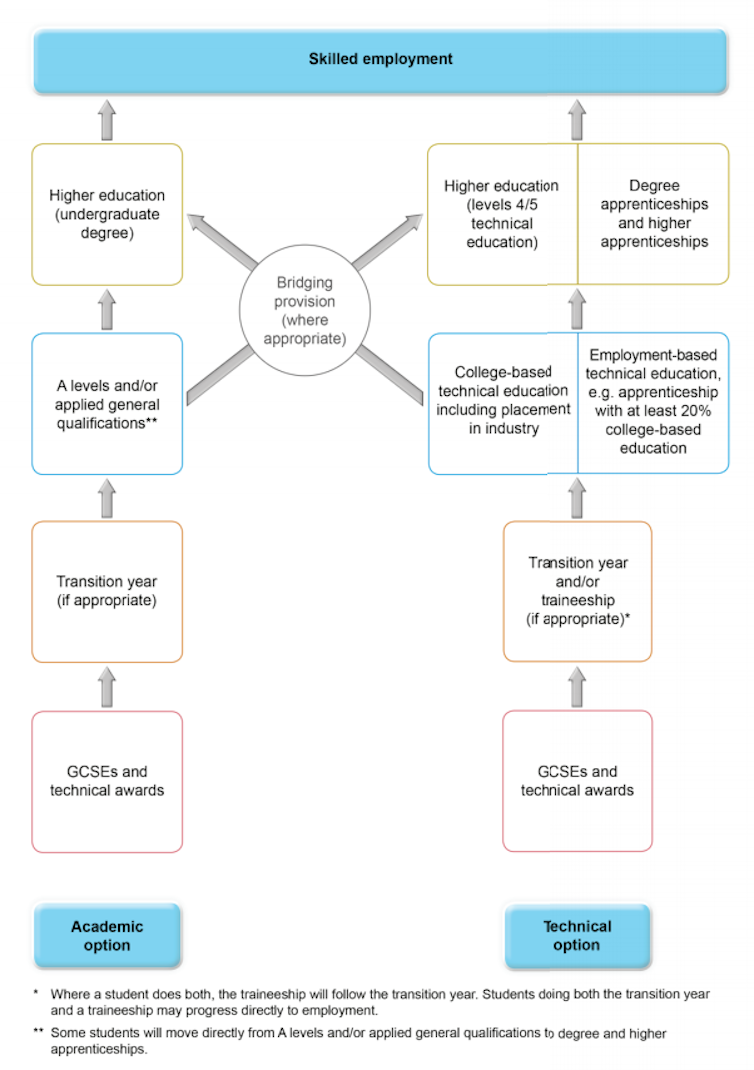

The UK has set out a plan to reform English vocational education. It’s post-16 skills plan will establish two educational tracks for students over 16 years old by building a technical education route to go alongside the well-established academic track.

The aim is to strengthen vocational education – now called “technical education” – which a series of reports found to be an incoherent mishmash of vocational, general and academic studies with weak educational and employment outcomes.

Two options within technical education

The technical route will have two options: college-based technical education, which will include industry placements, and employment-based technical education, such as apprenticeships, which include at least 20% college-based education.

College-based technical education will extend to diploma level and employment-based technical education will extend to baccalaureate level, incorporating the 1,000 degree apprenticeships which have been established since 2013.

This would reverse the blurring of academic, general and vocational education, which has been a major trend over the last few decades in England, as it has been in Australia, the US and elsewhere.

Fifteen education routes

The government will establish 15 technical education routes, which group occupations with shared requirements.

The routes were derived from an analysis of current labour market information and projections of future skills needs, which were reviewed with employers, academics and occupational bodies.

The technical education routes are based on related occupations rather than sectors. For example, the digital route includes many occupations such as web designer and network administrator, most of whom are employed outside the IT sector.

These technical education routes will help streamline the education system, providing clearer options for students in Years 11, 12 and 13.

Reject the market in qualifications

In England, vocational qualifications are designed and awarded by 158 different awarding organisations. Many of these are private for-profit companies, which seek to increase their business by multiplying qualifications.

In 2015, there were over 21,000 vocational qualifications. Prospective plumbers, for example, have to choose from 33 qualifications offered at three different levels by five different awarding organisations.

The government expressed concerns about the qualifications market:

Instead of competition between different awarding organisations leading to better quality and innovation in the design of qualifications, it can lead to a race to the bottom in which awarding organisations compete to offer qualifications which are easier to pass and therefore of lower value.

Reject competency-based training

In a move that should provoke deep reflection by Australian policymakers, the UK government’s panel rejected the competency-based training of Australian vocational education qualifications:

We considered whether the current National Occupational Standards (NOS) could form the basis of technical education. However, NOS have been derived through a functional analysis of job roles and this has often led to an atomistic view of education and a rather tick-box approach to assessment. As such we do not consider them to be fit-for-purpose for use in the design of the technical education routes.

Public funds should not be allocated to for-profit providers

The panel estimated that at least 30% of government funding for English vocational education is allocated to private providers.

But there was a strong view that public funds should not be allocated in this way:

Given what appears to be the highly unusual nature of this arrangement compared to other countries and the high costs associated with offering world-class technical education, we see a strong case for public funding for education and training to be restricted to institutions where surpluses are reinvested into the country’s education infrastructure.

It was suggested that publicly subsidised technical education should be delivered under not-for-profit arrangements and that new government funding should be “prioritised towards colleges and training providers who intend to reinvest all surpluses into education infrastructure”.

Implications for Australia

This has direct implications for Australia, where private providers now offer 46% of government-funded vocational education. This is an extraordinary increase on the 29% share they had in 2011.

Australia might also consider the UK’s apprenticeship levy, which will be introduced from April 2017.

The levy will require employers with a payroll of over £3 million (A$5.2 million) to spend 0.5% of that on approved apprenticeships.

This will be similar to – but more rigorous than – the training guarantee Australia introduced in 1990 as part of the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS).

While training levies work well in 62 developed countries such as Austria, Denmark and France, Australia withdrew its training guarantee in 1994 because it was unpopular among employers and was weak.

But the collapse in apprenticeship numbers and the 31% cut in government funding per vocational education student since 2005 may prompt the government to consider following England in introducing an apprenticeship levy.