The brain is key to our existence, but there’s a long way to go before neuroscience can truly capture its staggering capacity. For now, though, our Brain Control series explores what we do know about the brain’s command of six central functions: language, mood, memory, vision, personality and motor skills – and what happens when things go wrong.

When you read something, you first need to detect the words and then to interpret them by determining context and meaning. This complex process involves many brain regions.

Detecting text usually involves the optic nerve and other nerve bundles delivering signals from the eyes to the visual cortex at the back of the brain. If you are reading in Braille, you use the sensory cortex towards the top of the brain. If you listen to someone else reading, then you use the auditory cortex not far from your ears.

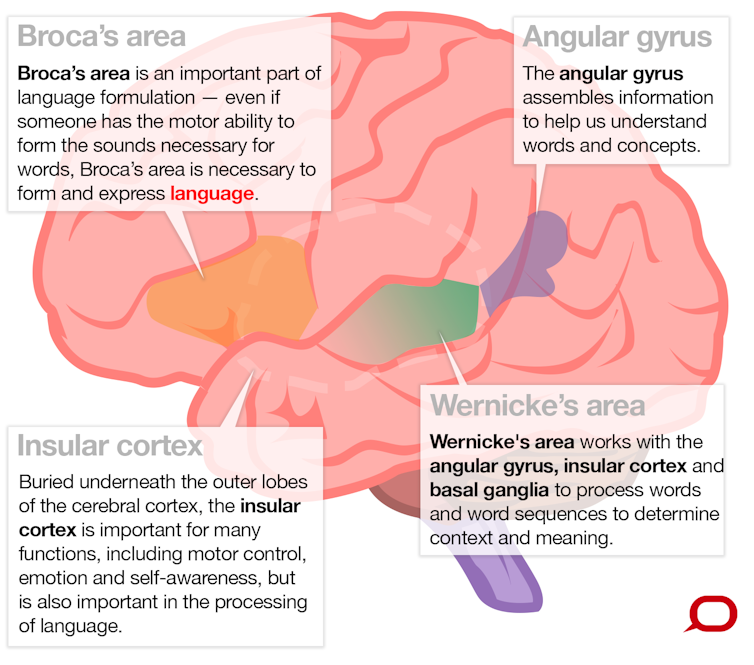

A system of regions towards the back and middle of your brain help you interpret the text. These include the angular gyrus in the parietal lobe, Wernicke’s area (comprising mainly the top rear portion of the temporal lobe), insular cortex, basal ganglia and cerebellum.

These regions work together as a network to process words and word sequences to determine context and meaning. This enables our receptive language abilities, which means the ability to understand language. Complementary to this is expressive language, which is the ability to produce language.

To speak sensibly, you must think of words to convey an idea or message, formulate them into a sentence according to grammatical rules and then use your lungs, vocal cords and mouth to create sounds. Regions in your frontal, temporal and parietal lobes formulate what you want to say and the motor cortex, in your frontal lobe, enables you to speak the words.

Most of this language-related brain activity is likely occurring in the left side of your brain. But some people use an even mix of both sides and, rarely, some have right dominance for language. There is an evolutionary view that specialisation of certain functions to one side or the other may be an advantage, as many animals, especially vertebrates, exhibit brain function with prominence on one side.

Why the left side is favoured for language isn’t known. But we do know that injury or conditions such as epilepsy, if it affects the left side of the brain early in a child’s development, can increase the chances language will develop on the right side. The chance of the person being left-handed is also increased. This makes sense, because the left side of the body is controlled by the motor cortex on the right side of the brain.

Selective problems

In 1861, French neurologist Pierre Paul Broca described a patient unable to speak who had no motor impairments to account for the inability. A postmortem examination showed a lesion in a large area towards the lower middle of his left frontal lobe particularly important in language formulation. This is now known as Broca’s area.

The clinical symptom of being unable to speak despite having the motor skills is known as expressive aphasia, or Broca’s aphasia.

In 1867, Carl Wernicke observed an opposite phenomenon. A patient was able to speak but not understand language. This is known as receptive aphasia, or Wernicke’s aphasia. The damaged region, as you might correctly guess, is the Wernicke’s area mentioned above.

Scientists have also observed injured patients with other selective problems, such as an inability to understand most words except nouns; or words with unusual spelling, such as those with silent consonants, like reign.

These difficulties are thought to arise from damage to selective areas or connections between regions in the brain’s language network. However, precise localisation can often be difficult given the complexity of individuals’ symptoms and the uncontrolled nature of their brain injury.

We also know the brain’s language regions work together as a co-ordinated network, with some parts involved in multiple functions and a level of redundancy in some processing pathways. So it’s not simply a matter of one brain region doing one thing in isolation.

How do we know all this?

Before advanced medical imaging, most of our knowledge came from observing unfortunate patients with injuries to particular brain parts. One could relate the approximate region of damage to their specific symptoms. Broca’s and Wernicke’s observations are well-known examples.

Other knowledge was inferred from brain-stimulation studies. Weak electrical stimulation of the brain while a patient is awake is sometimes performed in patients undergoing surgery to remove a lesion such as a tumour. The stimulation causes that part of the brain to stop working for a few seconds, which can enable the surgeon to identify areas of critically important function to avoid damaging during surgery.

In the mid-20th century, this helped neurosurgeons discover more about the localisation of language function in the brain. It was clearly demonstrated that while most people have language originating on the left side of their brain, some could have language originating on the right.

Towards the later part of the 20th century, if a surgeon needed to find out which side of your brain was responsible for language – so he didn’t do any damage – he would put to sleep one side of your brain with an anaesthetic. The doctor would then ask you a series of questions, determining your language side from your ability or inability to answer them. This invasive test (which is less often used today due to the availability of functional brain imaging) is known as the Wada test, named after Juhn Wada, who first described it just after the second world war.

Brain imaging

Today, we can get a much better view of brain function by using imaging techniques, especially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a safe procedure that uses magnetic fields to take pictures of your brain.

Using MRI to measure brain function is called functional MRI (fMRI), which detects signals from magnetic properties of blood in vessels supplying oxygen to brain cells. The fMRI signal changes depending on whether the blood is carrying oxygen, which means it slightly reduces the magnetic field, or has delivered up its oxygen, which slightly increases the magnetic field.

A few seconds after brain neurons become active in a brain region, there is an increase in freshly oxygenated blood flow to that brain part, much more than required to satisfy the oxygen demand of the neurons. This is what we see when we say a brain region is activated during certain functions.

Brain-imaging methods have revealed that much more of our brain is involved in language processing than previously thought. We now know that numerous regions in every major lobe (frontal, parietal, occipital and temporal lobes; and the cerebellum, an area at the bottom of the brain) are involved in our ability to produce and comprehend language.

Functional MRI is also becoming a useful clinical tool. In some centres it has replaced the Wada test to determine where language is in the brain.

Scientists are also using fMRI to build up a finer picture of how the brain processes language by designing experiments that compare which areas are active during various tasks. For instance, researchers have observed differences in brain language regions of dyslexic children compared to those without dyslexia.

Researchers compared fMRI images of groups of children with and without dyslexia while they performed language-related tasks. They found that dyslexic children had, on average, less activity in Broca’s area mainly on the left during this task. They also had less activity in or near Wernicke’s area on the left and right, and a portion of the front of the temporal lobe on the right.

Could this type of brain imaging provide a diagnostic signature of dyslexia? This is a work-in-progress, but we hope further study will one day lead to a robust, objective and early brain-imaging test for dyslexia and other disorders.

Want to know how the brain controls your mood? Read today’s accompanying piece here.