Before a crucial week of interest rate decisions for central banks, and on the eve of the emergency takeover of banking giant Credit Suisse, the Bank of England and five other major central banks announced a coordinated effort to boost the flow of US dollars through the global financial system.

Their aim was to keep credit flowing to businesses and households during recent banking sector turmoil. This had to coincide with ongoing attempts to control inflation amid market chaos.

The measure implemented by the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, the Swiss National Bank and the US Federal Reserve extended existing arrangements called “liquidity swaps” by increasing the frequency with which these central banks can exchange US dollars, from weekly to daily, at least until the end of April 2023.

Liquidity swap agreements are an important channel through which US dollars are made readily available to all major countries. The change in frequency from weekly to daily is designed to shore up stability. But uncertainty remains about whether the financial system has recovered from recent turmoil, and such tools still carry risks.

What are liquidity swaps?

Liquidity swap agreements are commonly used to enable central banks to exchange currencies using an agreement based on collateralised loans. They allow a central bank (the recipient) to obtain foreign currency from another (the source) and distribute it to commercial banks in their own country.

Agreements are often reciprocal, in that there is a two-way liquidity line and either bank can take up the recipient or source role. Central banks have a multitude of these agreements in place at any one time with other key central banks.

The reason for the recent increase in the availability of US dollars through these agreements is that the dollar is the dominant global currency. It plays a large role in trade and comprises significant chunks of investors’ portfolio holdings.

Of course, commercial banks have assets and liabilities denominated in many different currencies. But it’s not unheard of for non-US banks to have large – sometimes even roughly the same – amounts of US dollar-denominated assets as US banks.

So, these liquidity lines provide a way for commercial banks to get a currency they need but that their central bank may not have in abundance. Without this tool, non-US banks would have to acquire US dollars through their own markets or by lending in non-US markets in exchange for US dollars.

But any stress in the market, such we have seen recently with Credit Suisse, can lead to increased demand for cash as investors try to safeguard their assets. Because of the dominance of the US dollar in the global financial system, this can cause a shortage of dollars available to non-US banks. These banks then have to turn to their own central banks for US dollars – and this is where swap lines come in.

Lender of last resort

In a world of interconnected markets, negative financial events can spread quickly. Coordinated movements by central banks remind everyone that they can and will act as a lender of last resort.

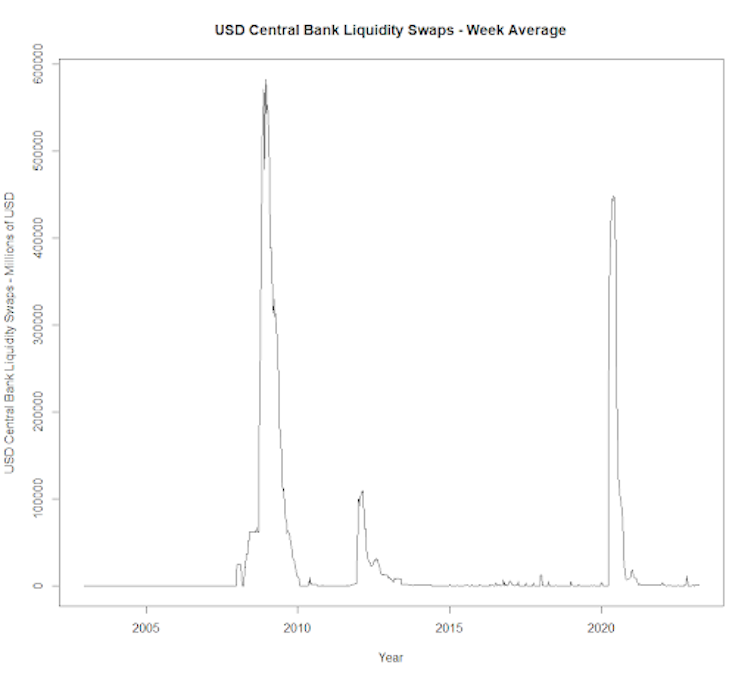

The chart below shows the weekly average amount of US dollars transacted through these liquidity lines. These trades tend to increase during adverse times, such as between 2008 and 2010 due to the global financial crisis, and in 2020 at the beginning of the COVID pandemic.

Use of USD central bank liquidity swaps:

So, when central banks boost accessibility to dollars through these liquidity lines – as they are now – it suggests they are concerned about whether weekly access to US dollars is enough. In other words, when they have growing concerns about financial stability, they want to remind markets that they will act as a lender of last resort.

For the recipient central banks, the active lines can help prevent costly bank failures and can dampen domestic concerns about bank runs. For the source (typically the Federal Reserve), the liquidity lines maintain demand for US-denominated assets and prevent spikes in interest rates, which in turn supports US interests.

But this gives rise to another problem: moral hazard. The increasing frequency of liquidity lines can act like a subsidy for US dollar-based activities. Excessive amounts of this behaviour can in turn cause more instability even as central banks are trying to calm markets with these tools.

Financial (in)stability

And moral hazard is not the only kind of risk these tools carry – liquidity lines can act as a useful medicine, but they do have side effects. There are two key components to a liquidity line that determines the potential risk to, and broader effect on, the financial system.

The first comes from the way they are agreed between central banks, and the second comes from how the recipient central bank passes the US dollars from the swap on to commercial banks in its own country. A recipient central bank is solely responsible for paying the source central bank for the US dollars, so the source central bank does not know the identity of the beneficiary banks in the commercial markets.

This creates supervisory and regulatory problems because the source is not able to regulate the foreign commercial banks that access these swaps via recipient banks. All central banks have their own incentives and rules around how and why they operate. So, this exposes a central bank to any risks arising from the decisions made by banks in other jurisdictions, some of which will operate based on different incentives and oversight.

This is why central banks need to use such tools with caution, particularly when they are trying to encourage stability. Liquidity lines can actually cause fires started in one country to spread through others, which could destabilise the global financial markets.