Only a quarter of the British public feel able to define what extremism is, according to a survey by the Commission for Countering Extremism. The findings, released in mid July, suggest that the Home Office needs to do more to get across its message on extremism and how it might be tackled.

More than 2,500 members of the public responded to a call for evidence from the commission as part of an effort to measure the public’s understanding of extremism and their experiences of it. Led by human rights activist Sara Khan, the commission was established in March 2018 to understand and help tackle extremism in England and Wales.

While those who put themselves forward to answer surveys are rarely considered to be a representative sample of the public at large, the data provide strong clues about the nation’s attitudes.

The government currently defines extremism as:

The vocal or active opposition to our fundamental values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and the mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. We also regard calls for the death of members of our armed forces as extremist.

But only a quarter of the respondents said they found this definition helpful, raising questions as to whether it remains fit for purpose.

Despite these uncertainties around what extremism means, around half of the respondents appear to know it when they see it, whether in their local area, further afield or online. And 52% said they had witnessed something they would regard as extremism.

The data also shed light on public sensitivity towards “Muslim or Islamist extremism”. Nearly 60% had witnessed it in some form, nearly twice as many as had experienced far-right extremism. This presents a challenge for the Home Office. How does it address public concerns around Islamist extremism without limiting the democratic rights and freedoms of a sizeable minority of the population?

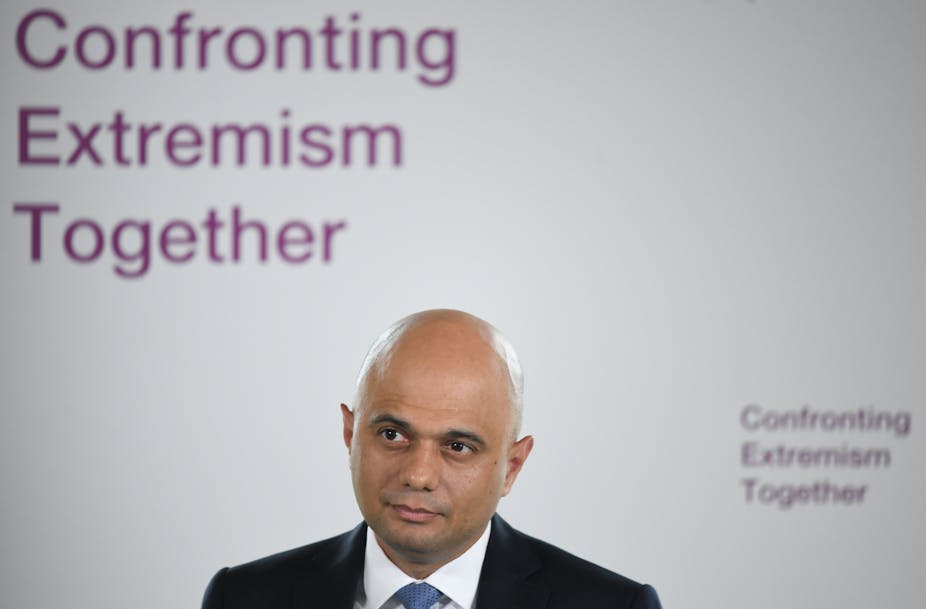

One answer might be to focus on victims and concrete examples of victimisation rather than on the more common abstract notions of a general threat to everyone. In late July, the then home secretary, Sajid Javid, said reports of extremism were rising in the UK, a threat “now worse than ever”.

But statements such as these leave important questions unanswered. Where is the threat of extremism rising? By how much? And for whom? Are there particular people and groups who are more vulnerable to beliefs and actions that seek to harm, coerce or exclude than others? And are there factors that increase vulnerability?

What it is and how to tackle it

While a third of respondents agreed that everyone is at risk from extremism, religious and ethnic communities were identified as the most vulnerable social groups. These are important insights that could provide the basis for an approach that puts victims at the centre of counter-extremism policy.

The survey also revealed that the public is ready to identify a wider range of extremism than some might have supposed. Nearly a third of respondents had witnessed “far-left extremism” and one in five had witnessed “anti-government or anarchist extremism”.

The data also shed light on the attitudes, activities and behaviours witnessed by those who responded. Respondents were asked: “What attitudes, activities or behaviours have you witnessed that you regard as extremism?” In terms of “Muslim or Islamist extremism”, criminal offending, terrorism links and segregation were the most frequently selected responses. In terms of “far-right extremism”, extremist events, criminal offending and propaganda were the most frequently selected.

These findings show that respondents linked criminality to extremism but also that they were sensitive to the differences between its two most frequently recognised forms – far-right and Islamist.

While 71% were unsure about whether more should be done to tackle extremism, 38% placed emphasis on faith groups and leaders having a role in improving counter-extremism. Only half as many respondents said social media and tech companies and national government should improve counter-extremism, 21% for each. These findings suggest a public appetite for a more focused and bottom-up approach to tackling religious extremism.

A conversation worth having

The appointment of Khan and the ongoing work of the commission have been criticised by people and groups who represent, or claim to represent, the interests of British Muslim communities, including the Conservative peer Sayeeda Warsi and the campaigning organisations MEND and Cage. Initial criticisms focused on Khan’s suitability as a leader given her previous government ties as a member of a Home Office extremism and radicalisation working group, and included allegations that the commission seeks to unfairly target British Muslim communities.

We should expect differences of opinion given that there an estimated 4m British Muslims. But more recent criticisms from Cage about the commission’s “abject failure” are unhelpful for two reasons. First, the commission is collecting valuable information on far-right groups that are seeking to stir up and legitimise anti-Muslim hatred. Second, its data could lead to far more meaningful debates around what the British public considers to be extreme.

As a plural and diverse nation, the UK may never agree on where the mainstream ends and extremism begins. But a better-informed public debate, the kind the commission is seeking to encourage, may help us forge a broader consensus.