Philadelphia’s hip Northern Liberties community is an old working-class neighborhood that has become a model of trendy urban-chic redevelopment. Crowded with renovated row houses, bistros and boutique shops, the area is knit together by a pedestrian mall and a 2-acre community garden, park and playground space called Liberty Lands.

First-time visitors are unlikely to realize they’re standing atop a reclaimed Superfund site once occupied by Burk Brothers Tannery, a large plant that employed hundreds of workers between 1855 and 1962. And even longtime residents may not know that the 1.5 square miles of densely settled land around the park contains the highest density of former manufacturing sites in Philadelphia.

Over the past 60 years, more than 220 factories operated in this same small area. Nearly all did business before the mid-1980s, when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency started requiring businesses to report releases of toxic materials

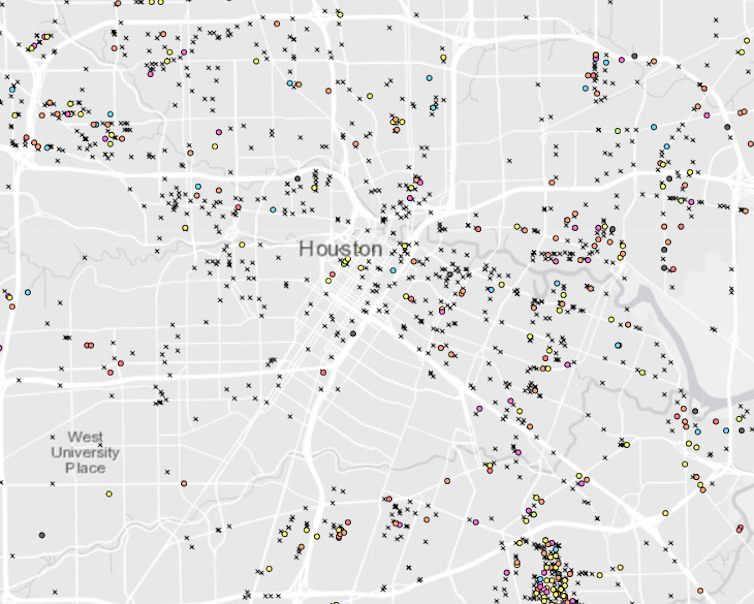

In our book, “Sites Unseen,” we set out to discover how many such former sites exist and why, over time, they simultaneously seem to proliferate and disappear from view. The data we collected from state manufacturing directories dating back to the 1950s don’t tell us whether specific addresses we found are presently contaminated. But they do provide richly textured maps of where and for how long hazardous industrial activities operated in four very different cities – New Orleans, Minneapolis, Portland and Philadelphia. Our findings strongly suggest that these and many other American cities now face a legacy hazardous waste problem they don’t even know they have.

Hazardous waste legacies

According to data recently released by the EPA, in 2017 industrial facilities (excluding mining operations) released 1.1 billion pounds of hazardous waste at the point of production or “on site.” That number is an understatement, because government records rely on voluntary reporting and exclude smaller manufacturing facilities that also pollute. And there is virtually no public documentation of similar releases before the 1980s.

To investigate the scope and scale of this problem, we identified relic and active sites from state manufacturing directories, which can be found in public libraries nationwide. These guides are largely untapped sources of information about where manufacturing activities occurred, for how long, and what each facility produced. In each city we analyzed, we were surprised to learn that government databases ostensibly designed to identify hazardous sites actually captured less than 10 percent of historically existing manufacturing sites.

Through follow-up surveys, we learned that 95 percent of relic manufacturing sites are used today for activities other than hazardous industry. We found coffee shops, apartments, restaurants, parks, child care centers and much more at these locations. These patterns corroborate processes which we now suspect drive both the spread of contaminated urban lands and the concealment of their past uses.

Erasing sites’ history

Like other businesses, most hazardous industrial facilities operate for a time, then go out of business or move their operations elsewhere. This constant turnover is an ongoing, fundamental feature of urban economic development. And because urban land is limited and valuable, those lots typically are redeveloped for non-industrial uses when they become available.

Our data show that hazardous industrial sites turn over every eight years, on average. This means that an individual lot can be redeveloped multiple times, sometimes over the span of just a few decades. For example, one Portland, Oregon address that we investigated housed a neon sign and sheet metal fabricator during the 1950s, then the office of a dry bulk trucking company, and is now a doggy day care center.

These interlocking processes of land use and reuse have far-reaching environmental impacts that social scientists are only beginning to recognize. Lot by lot, small but ongoing changes in urban land uses spread toxins across urban areas. At the same time, pressures for redevelopment often cover up the evidence.

In these ways, large, long-lived industrial sites, like the former Burk Brothers Tannery in Philadelphia, represent the tip of the iceberg of urban industrial activities and resulting contamination. Government agencies typically identify and clean up these large, visible sites that are known or widely suspected to be contaminated. And often they offer developers incentives to build on them, including liability waivers.

All the while, thousands of smaller, less prominent but potentially polluted sites go unnoticed, contributing to a much more systemic environmental risk.

Look back to move forward

Based on the research we did for our book, we believe the problem of relic industrial waste is far greater and more vexing than many scholars, regulators and developers appreciate. And this complexity has important implications for environmental justice and the question of who lives, works and plays in neighborhoods burdened by relic industrial contaminants. Communities can’t set priorities for cleaning up contaminated land until they identify relevant sites.

Environmental justice studies that use more limited government data on hazardous sites provide consistent evidence that polluting industries and environmental hazards are more frequently imposed on poor and minority communities. But our findings suggest that, over time, risks also accumulate over broader areas – including white working-class neighborhoods of yesteryear, lower-income and minority neighborhoods that superseded them, gentrifying areas such as Philadelphia’s Northern Liberties that are now selectively following, and whatever comes after that.

It is a basic social fact of urban life that industrial hazards accumulate and spread relentlessly. The sooner this problem is recognized, the sooner Americans can reclaim their cities and the environmental regulatory systems that are designed to ensure our collective well-being.

One way forward is for regulatory agencies to undertake historical investigations of relic industrial sites, using the same publicly available sources that we have used. Concerned citizens and neighborhood groups can do so as well, and the DIY User’s Guide at the end of our book describes how to do it.