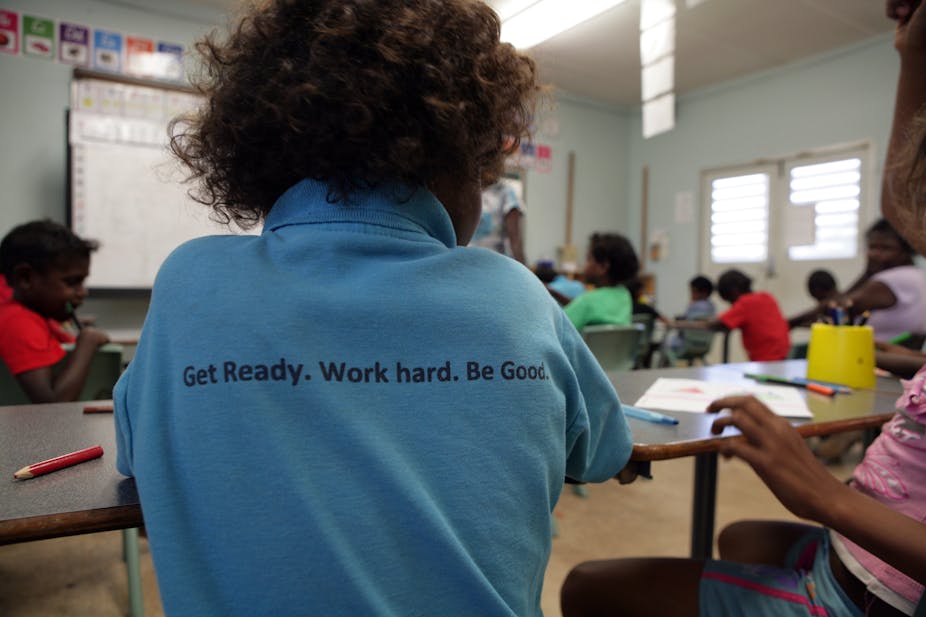

Aurukun School in Cape York, far north Queensland, closed in May this year after a series of violent episodes directed at teaching staff.

The school is one of the Cape York Academy schools operating under the stewardship of prominent Indigenous leader Noel Pearson.

Pearson was given state and federal funding to take over the running of the Cape York schools because they weren’t doing as well as Department of Education schools. Attendance was low, behaviour poor and academic results were well below par.

So why not try giving the schools more autonomy to operate a curriculum that responds to local circumstances, rather than a curriculum conceived and managed from a distant and out-of-touch Brisbane or Canberra?

So far so good.

Direct Instruction

The Academy schools then imported a curriculum from even more distant Eugene, Oregon in the US.

It is called Direct Instruction, or DI, and it costs Aurukun school close to A$2 million a year. That is a lot of Australian tax payer money going to the US developer, the National Institute for Direct Instruction (NIFDI).

As a consequence of this year’s turmoil, the Queensland Department of Education conducted a review of Aurukun school and made numerous recommendations, including the scaling back of DI in the school.

A close reading of the review reveals the many ways in which DI has been a failed experiment in Aurukun.

Learning English is not a learning disability

Direct Instruction is a teaching methodology developed for English speaking children with cognitive dysfunctions that inhibit their capacity to process language.

The children in Aurukun do not have learning disabilities, they are simply learning English as an additional language.

They speak Wik as their first language. Many also speak additional dialects or creoles in their daily lives. These children are linguistically proficient, and their language processing capabilities are superior to the majority monolingual English speaking population of Australia.

DI is, quite simply, the wrong intervention for the children of Aurukun.

What matters more - the teacher or the program?

A key rationale for implementing DI was to counter the high teacher attrition rates in remote indigenous communities like Aurukun. The program would be constant, even if the teachers weren’t.

DI is fully scripted, and teachers must not diverge from the script. Neither the lesson planning nor the assessment is conducted by the teachers. The program’s selling point is that it “teacher proofs” the curriculum.

Anybody can deliver the script on any given day because it is the program that does the teaching, not the teacher. The data from each week’s teaching is sent to Cairns where it is number crunched by National Institute for Direct Instruction (NIFDI) personnel and students are promoted or demoted based on that analysis.

Teachers are completely removed from the learning equation.

It is fortunate, then, that DI is designed to be impervious to high teacher turnover because teacher retention at Aurukun is about 64% compared to 90% in the rest of the state, and teacher morale has dropped from 94% to 40% over the past four years.

As long as it gets results

All the criticisms of DI would fade to grey if the results were good, but they are not.

The school’s national literacy and numeracy results (NAPLAN) remain well below the national benchmarks on every measure of reading, writing, spelling, grammar and numeracy.

Very modest in-school improvements have been recorded in some areas. However the sample size for those results renders them invalid. The school has one of the lowest NAPLAN participation rates in the state - only 14 of the 28 children in Year 3 sat the test in 2015. And the Department’s report implies that they might have been the “good” students.

For the past five years, every school day, from 8.30am to 2.30pm, has been entirely devoted to teaching literacy and numeracy through the DI program.

But the results indicate an extraordinarily poor return on money and time invested.

Engagement is key

DI program material is patriotically North American. It is far removed from the day to day lives of the children of Cape York, or any Australian child. As one teacher told the review:

“They learn about July 4 Thanksgiving and the stories they listen to are about American states. The kids know more about American states than Australian.”

No other curriculum work is done. There is no hands-on solving of mathematical problems, or reading of authentic literature. No exploration of Australian history, or science concepts, and certainly no 21st-century curriculum innovations like coding.

It’s an old, white, American curriculum. No wonder only 50% of the kids turn up for class, and are poorly behaved when they do.

Direct Instruction versus explicit instruction

Direct Instruction is not to be confused with the educational principle of explicit teaching. DI is the copyright name of a commercial program.

The children of Aurukun do need explicit teaching, as do most children.

They need to be shown how English works because it is not their first language, and because proficiency in English is crucial to success in Australian society.

They need to be taught by English language specialists who can develop a program that explicitly teaches how the English language works through engaging the children with their local environment, reading real books and nurturing their existing multilingual proficiency.

A lesson learned?

What has happened in Aurukun is a lesson.

This is what happens when you out-source education to commercial interests.

This is what happens when you think it is easier and cheaper to buy a program than invest in teacher professional development.

This is what happens when you take a remedy for a specific learning difficulty and apply it to children who don’t have that difficulty.

Let’s hope it’s a lesson well learned.