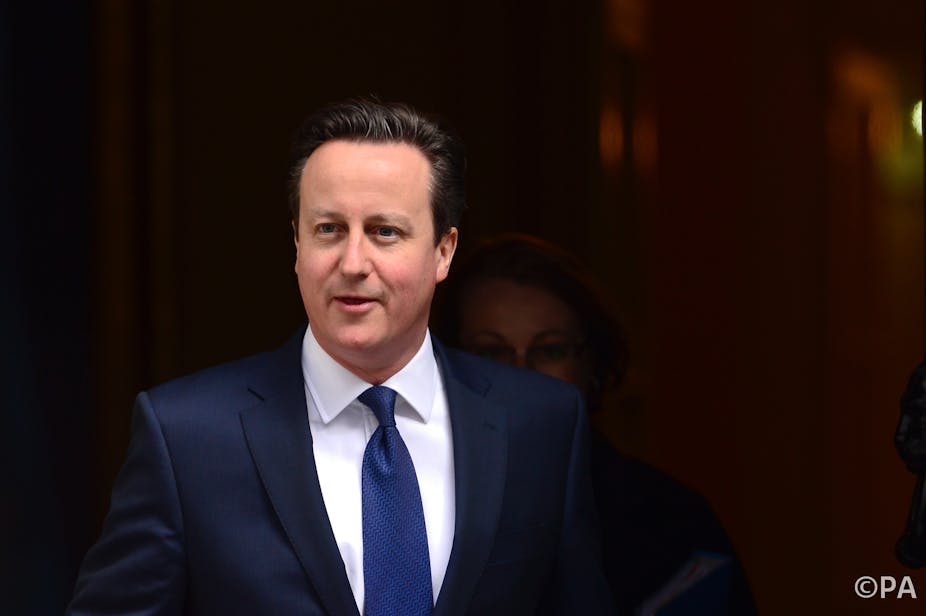

David Cameron has announced, at the end of his first term as prime minister, that he would not serve a third term. In a BBC interview, he said that “terms are like Shredded Wheat: two are wonderful but three might just be too many”.

This slightly bizarre revelation has proved a political gift to the opposition. There are several unusual things about it. It is rather presumptuous to pre-announce a retirement before actually being re-elected – a point the opposition parties were quick to jump on.

In any case it has diverted attention, in the midst of an election campaign, firmly onto process politics and away from policy.

So why did he do it? There are three plausible explanations.

It was an accident

Perhaps Cameron was quite simply speculating on his status and position, as prime ministers are wont to do. He was asked a question and he answered honestly, without obfuscating or thinking of the implication of his words – unusual for a senior politician.

Cameron isn’t always careful with his speculations, as his bread-maker gaffe or now numerous Twitter stumbles have proven. His supposed indiscretion about the Queen “purring” down the phone to him after the Scottish Independence referendum, may not have been such a mistake.

That said, in public relations terms, the fact that the interview occurred in the well-appointed kitchen of his home in the Cotswolds adds an unwelcome layer of poshness to this possible gaffe.

He was making space

Perhaps it was deliberate and he was trying to “do a Blair by attempting to carve out space to do things he wants to do before he goes. By pre-announcing his retirement (if re-elected) he can focus on some key policy achievements, and shelve leadership speculation until later.

Tony Blair did this before the 2005 election, recalling in his memoirs that he did so "against much advice … as many people thought it was fatal ever to say when you may stand down.”

He claims to have been under a great deal of pressure to announce an exit plan, as Gordon Brown was “still in a highly dangerous mood”, and justified it by saying that not providing a date “was the view Thatcher took, and a fat lot of good it did her”. He claims to have concluded by 2004 that “past a certain point, you are damned either way”.

Yet Cameron does not appear to be at any Blair-esque “certain point” – unless he’s under some pressure or threat we don’t know about. But he did also mention his commitment to future education reforms, and clearly asserted he was only “half done”. Perhaps he was asking for time, or playing for it.

He was signalling his intent

It may be Cameron is trying to display a confidence to his supporters and challengers. There have been ominous rumours about Cameron’s post-election safety, and in that light, his comment may be the political equivalent of an economic signalling effect, directed at those who will hear that he thinks he can win and is looking to his future.

In that regard, perhaps this is just a messy and watered-down equivalent of Thatcher’s famous pledge in 1987 to “go on and on”.

But whatever the reasons for this slip, deliberate or otherwise, Cameron has set in motion speculation and chatter that will distract and potentially undermine the Tory campaign. He has effectively fired the starting gun for the party leadership, going as far as naming three potential successors: Boris Johnson, George Osborne, and Theresa May.

There is a serious risk that in the unlikely event that he leads the party to win a majority at the election, he will become a lame duck leader – and the danger is even more acute if he ends up leading a minority government. In any case, his wish to serve the full term is rather fanciful, since any new leader would surely need time to bed in before fighting the 2020 election.

Cameron’s leadership capital consists in maintaining a level of control over his own destiny. Politicians themselves are acutely aware of their finite “stock” of authority, and of the ticking clock. Having plenty of leadership credit means a leader can get things done by “spending” or “leveraging it” – think Tony Blair in 1997 or Barack Obama in 2009, who both temporarily had the kind of authority that comes from dizzying levels of support, popularity and momentum.

By surrendering his sole hold on the leadership, even in the far future, Cameron’s capital is now going to be badly depleted – perhaps fatally judging by the frantic damage limitation exercise currently underway.

His new “shredded wheat” analogy has definitely added something to the folk lexicon of British leaders. You could respond by pointing out, of course, that it depends on how hungry you are and the size of the bowl.