The summer of 1985 is oppressive around the medieval Italian town of Gubbio. Thick heat is held captive in the wooded ravines and the windless slopes that climb and crawl across Umbria and on to the foothills of the Apennines. A short winding drive into the hills behind the town is the Libera Università di Alcatraz, a secluded retreat that is in the process of establishing itself as a gathering place for artists, writers and thinkers – a place where they can escape to nature and create.

In the Italian fashion, not everything is up and operating. Buildings stand half-finished. The swimming pool has been drained so a mural of a dragon can be painted on the bottom. But somehow the place works. Guests commune with their muses during the day, then congregate for meals on the terrace in the still, warm evenings to enjoy rustic fare prepared from local ingredients, washed down with red wine and tales from the assembled creatives.

The enterprise is run by Jacopo Fo, 30 years old and turning his hand to every aspect of the business, including the swimming-pool dragon. Until the artwork is finished, the pool can’t be filled to give the guests some respite from the relentless summer heat.

Amid the dust haze and the fireflies that swarm the air, an unlikely gathering is taking place. Jacopo’s parents are in town: Dario Fo and Franca Rame. They are setting up camp at Jacopo’s enclave to rehearse a new play.

Fo and Rame are Italian cultural royalty. It is still 12 years until actor and playwright Fo will be recognised with the Nobel Prize for Literature, but he is already well-established as a national treasure. His groundbreaking work in commedia dell’arte flipped the nature of theatre. His plays present characters as grotesques who directly address the audience. Their anarchic asides are an assault on classical theatre’s embrace of the heroic lead.

Fo’s new play – Elizabeth: Almost by Chance a Woman – will be performed by a drama company from Finland. It is due to premiere at the prestigious Tampere Theatre Festival in a matter of weeks.

The play is incomplete.

Fo speaks no Finnish.

The Finns speak no Italian.

An interpreter is hired to make sense of Fo’s instructions for the actors and the many rewrites that are taking place on a daily basis. Her name is Aira Pohjanvaara-Buffa. And since she is going to be camped out in the Umbrian woods for a month or so, she invites along her new partner. He is a respected but still mostly unknown British novelist by the name of Barry Unsworth.

At this point in his career, Unsworth had attracted a small but enthusiastic readership for his historical fiction. Seven years later, he will win the Booker Prize for Sacred Hunger, his novel set amid the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade.

So, from late June to mid-July of 1985, a future Nobel laureate and a future Booker Prize winner co-exist in the peace and bucolic calm of the Umbrian woods.

The rehearsals are a fiasco.

On the first day, the actors arrive drunk from the airport. The rehearsal stage is still to be built. Fo changes his script daily, hourly – often in the wings as the actors wait for fresh lines to be written for them. There are clashes between the traditional approach of the Finns and the anarchic methods of Fo and Rame. The lead actor is laid low with sunstroke. The director has brought his youthful boyfriend with him, and the young man starts to take an interest in some of the young women of the theatre company. Tempers run short in the unrelenting heat.

All the while, Unsworth keeps a meticulous diary, documenting the artistic approach of the enigmatic Fo, as well as the behind-the-scenes shambles of a production that seems destined for disaster.

For decades, the journal was forgotten. Bundled among the author’s papers and correspondence, it eventually found a home in the archives of the Harry Ransom Centre at the University of Texas in Austin. The diary is in Box 12, Folder 6 of the Unsworth papers. Its observations are written in clear cursive in what appears to be blue biro, with occasional red annotations.

It makes for sometimes brutal reading.

The journal provides a first person account of the creative process of one of the 20th century’s lions of theatre, in all its chaotic glory. Though it is a simple linear account of events, Unsworth manages to pen a compelling narrative and create fully realised characters.

Great promise

As with all such creative ventures, it starts with great promise.

June 20th – Drove from Rome to the Liberia Università di Alcatraz which is situated some few kilometres from Gubbio, and not far from Perugia. Gentle green hills of Umbria with the darker, higher slopes of Apennines behind. Walled hilltop towns. Scale of nearer hills small enough to be manageable but dramatically steep gorges, often thickly wooded. Alcatraz itself (near to hamlet of Santa Cristina) set in green hilly country 6000 metres above sea level.

But very quickly Unsworth senses some fragility in the foundations of the enterprise that lies ahead.

Of the Finnish company met at Rome one was very drunk already – another slightly. They had been drinking on the plane […] They both continued to drink steadily but the tight-featured one remained just short of being staggering drunk while the fair haired – more sensitive one I think – became helplessly drunk by evening, hardly able to talk.

This caused and still causes worry to Willi, who is the director of the Company (They are from Tampere, about 200 miles from Helsinki.) If they are not dealt with severely they could well fall into a pattern of drinking which could make them unfit for work and seriously prejudice progress of the play.

Even in his diary, it seems, Unsworth is not averse to a bit of dramatic foreshadowing. The future Booker winner is curious about the legend of Fo and whether the myth of the man measures up against the actuality. His descriptions, both of physique and psyche, are forensic.

Fo himself is not taking over the direction of the play, as his doctor has told him to go very easy. He will do an hour a day, or so he says now – later enthusiasms and involvements remain to be seen.

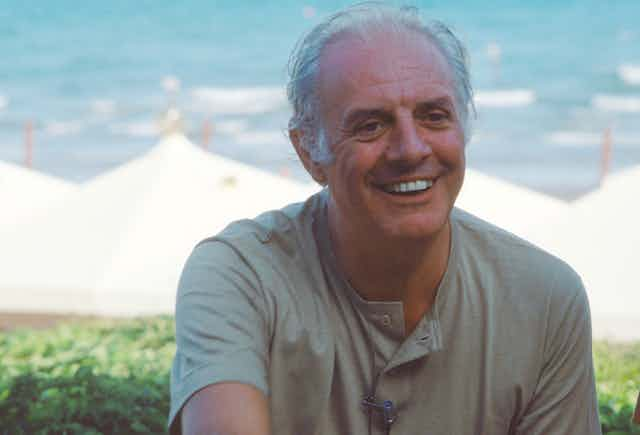

He is tall – at least six feet I should think – and portly, very carelessly dressed but despite this an imposing figure rather, with natural dignity and ease of manner. He is at first impression almost gubernatorial – almost Roman senatorial – in feature, big-faced, fleshy, with large slightly beaky nose, but this impression soon lost. If his face could be stilled and the smile removed monumental – 2 conditions never fulfilled. There is nothing monumental about the face, it has a refined seriousness and an alternation almost constant of vague abstraction and gentle shrewdness and alertness.

Under the good humour great reserve of firmness and a total dedication to the work. His eyes very bright blue, face florid I think through his recent illness. In contrast to the amazing repertoire and fluidity of movement pose and gesture when on stage, in conversation he is still, not very demonstrative at all (given he is Italian).

Unsworth revisits this perplexing nature of Fo’s character many times in the course of the journal. It is fair to say that the author is at first curious, then grows to admiration, and ultimately to great disappointment that the man is not the equal of the art that he produces. Fo’s veneer is as thin as any stage setting, with much the same remit: to paint an image that reminds the audience of something majestic in real life, but which is itself a simulacrum, a construction.

I visit the stage that Fo has had built in the bare hillside, on the crest of the slope, below the dust road that leads to the tower, stairs on the left leading up to a door – Elizabeth’s room. In the background an arched balustrade – I think with a narrow round platform below it. Six identical arches forming an arcaded effect […] not a means of exit or entry but to give the illusion of a palace interior. Right centre a curtained room. A life size horse on wheels. (This is to be improvised here – but needed for commercial production.)

This set does not change throughout the play. They are still working on it as I stand there. Fo moving planks, sweeping dust and debris from the stage area. The workmen with ladders, wheelbarrows, trestles, buckets.

The work is to be finished tomorrow or the day after – ready for rehearsals with the Finns. Not finished but it is an interior already – an enclosure (plank walls delimit it from the rock and scrub all round), something where things that are significant, that have causation or consequences, can be made to happen, presented.

When one artist views another whose work is in a different medium, it is often through the lens of their own craft. In Unsworth’s case, he is fascinated by Fo’s artistry on stage.

June 21st – The day begins with a talk by Dario on his attitude to theatre in general and then his intentions in this particular play. He speaks about the “classical theatre” so-called, which was an instrument of power because it took no account of day-to-day life and also denied independence to the actors.

Contrasts this with commedia dell’arte from which he draws his models: fixed characters which can represent different aspects of society, different foras in conflict etc. Speaks about the improvised quality in this popular theatre which enabled characters such as the donnazza and fool to comment on the action, to support grotesquely or to undermine values or show true nature of hypocritical positions of “heroic characters”, and also allowed these same characters to address asides or speak to the audience directly thus involving them more closely.

Fo stresses dignity of the individual within, stresses of power and manipulation and the purposes of the state. Explains that in this play “Elizabeth” he is trying to observe the rules and essential form of Italian dramatist of 15th century – unities of place, time, use of traditional characters etc. in order to illuminate the truth underlying platitudes and pieties of what is received as history.

The play is set in the court of Elizabeth I, where the Virgin Queen fumes about Shakespeare’s dramas satirising her reign and laments that her love, the Earl of Essex, is conspiring against her. As with much of Fo’s work, it is a treatise on the misapplication of power. His career was founded on his scathing satire of authoritarian regimes, with works such as Accidental Death of an Anarchist (1970) and Can’t Pay? Won’t Pay! (1974), which earned him widespread regard as a champion of the working poor.

Read more: Guide to the Classics: Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, a tragicomedy for our times

God motif

That night at dinner, the two actors who had been excessively drunk apologise to Fo, and he warns them of the consequences if they transgress again. The play’s director, Arturo Corso, arrives:

a lean restless sort of man with a thin, curiously bird-like face, bird-like or mammal-like? Prominent nose, big eyes, retreating chin. Clever eyes, ready smile, used to delivering himself, I think.

Also newly arrived is Corso’s youthful boyfriend, Alfredo:

very beautiful – with features bold and well shaped and those eyes of Italian youth, fathomless and shallow at the same time. At dinner Franca asked him (Corso) where Alfredo was sleeping. He said, “With me of course”. He uses the feminine pronoun when referring to Alfredo.

Unsworth’s observations of Fo and his methods begin to adjust almost immediately. His diary entry for June 22 notes that the Finns face a tough taskmaster when rehearsals start:

It is cold on the terrace in the mornings, out of the sun, but Dario has made up his mind that he will rehearse there. He is autocratic and heedless in matters of this kind.

Now I see in his face, a sort of epicene quality, a potential for collapse […] in contrast with the magisterial quality also there. It is as though in these two casts of his face is symbolised the recurrent theme of his plays, the conflict of power, the holding up and simultaneous undermining of authority.

He has amazing control over voice and face, so that in illustration he can roar with laughter, scream with outrage, without the eyes changing from the seriousness of their intent – and he returns to the normal tone of rehearsal immediately, without pause.

Very quickly, Unsworth settles on a God motif in his observations of Fo at work and at play. He notes the characters in the performance are, through their actions and thoughts, questioning the words of God. Fo’s constant editing and rewriting of his script, even during the course of the readings, is summarised as: “God changing the rules?”

It is at this point in the project that Alfredo reveals himself to be 16 years old. This prompts the journal observation from Unsworth that:

(While the Finns drink, the Italians attempt seductions.) The author/actor is like God because he sets actual physical bodies in motion.

The following day, in a portent of things to come, a hot water bottle is fetched for Franca Rame who has collapsed after the morning’s strenuous rehearsal.

Fo moves through all this, portly, avuncular, curiously heedless in old T-shirt and trousers. God relaxing with his creatures, but still not of them.

In the midst of rehearsals stretching through long days without a break, Unsworth occasionally separates from the company and enjoys walks through the surrounding hills, heavy with flowering gorse, wild sweet pea, poppies and cornflowers. It is on these sojourns that he starts jotting notes for a possible novel, about an internationally famous playwright and actor, who buys up a sizeable piece of land and builds a theatre in the wilderness:

A long terrace (conservatory), rooms for recalling, rehearsing a big dining room. Swimming pool. He converts old buildings, barns, towers – medieval buildings – into accommodation. The area is beautiful – this is the Garden of Eden and he is God. (God with a flaw?) As consort he has his actress wife.

The assistant director is Christ figure. A troupe of actors arrive to be rehearsed in a new play. Is this a medieval morality, an Elizabethan period play, a foreign play? Is it written or adapted by Playwright? It should be a) a comment on the nature of the Playwright; authority (This could be achieved though directional comment.), on the nature of political power with reference to the England of today, and the relationships within it.

Ten years later, Unsworth’s novel Morality Play, about a troupe of travelling players in 14th century England, is shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

Growing tensions

By June 24, the growing tensions in the company are becoming obvious. Fo’s constant script revisions and his reluctance to let Corso take on the full directorial role are causing stress among the players. Fo and Rame decide to decamp for a few days and leave Corso in charge.

The big ego reacts to exhaustion by seeking to simplify for itself, with consequent chaos.

Dario is out of this for the most part, though an occasional hovering presence. He shows unwillingness to sunbathe with the others. When he takes off his shirt – which he does at some distance – shows a good deal of sag and distinctly formed, even quite plump breasts, confirming that sense of him as physically feminine. (Though he has a strong male image too.)

Can it be that his unwillingness to sunbathe derives from this? Is our God vain?

For all of Unsworth’s reservations about Fo’s temperament and his substance, he is an unabashed admirer of his stagecraft. He describes Fo showing the actor playing the role of the Donnazza how to move:

His demonstration of the Donnazza’s slip – the backward glance, the flounce with the back skirts, the backward bending body, then the skip and slither, the discovery of the piss – the acceptance that there is a wooden horse that pisses – are all absolutely masterly – just as funny every time he does it (everyone laughs every time). For a heavy man he moves about the stage with astonishing lightness and grace – like a dancer, his movements timed and precise. (It is obvious that the space of the stage and the subjects in it are as negotiable for him as a familiar sitting room might be.)

In God’s kingdom, a word from on high carries a good deal of weight. On June 25, Unsworth records:

Dario tells me I have an “intelligent face” – una facia intelligente. In the peculiar circumstances of this place all compliments and comments from him have a binding force somehow, setting the seal on things – even creating the fact that he elects to comment on.

Unsworth, however, is not easily guiled with words of praise. His works abound with thematic critiques of the neo-liberalism of the Thatcher years and the devastating impact her government’s policies had on his native north of England. He has a northerner’s disdain of bombast and pretension, and it is with this mindset that Unsworth regards Fo’s everyday manner as being as performative as anything he does on stage:

One grows oppressed by the performance element. Because Dario is so much at the centre of things, jovial host, object of pilgrimage, author and exemplar and metteur en scene, it sometimes seems he is mediating life for us. Last night we were all called out to admire the sunset, this in the midst of dinner. I resisted the collective invitation for some time but was more or less pulled out by A. It was indeed a beautiful sunset – radiant and roseate, the low western clouds edged with bright gold, the higher ones curled and flung across the sky in great radiant swathes. “Raphaelesque” as Dario describes it. He is proud and rightly of the place, the thing he has created, and this includes the sunset and perhaps the whole of Umbria too. But none the less this sense (on my part) of oppression remains.

At the same time, the actors are growing weary of this difficult Zeus-like figure in their ranks.

Dario is hovering presence, rather dreaded by the Finns now because of his inevitable habit of changing text (because he sometimes imperfectly remembers it and also because he does not have patience to understand Finns’ difficulties with the style). He grows impatient if they do not immediately get what he means. I think everyone will be relived now when he and Franca leave (tomorrow?)

But even when Fo and Rame depart for a few days, the rehearsals are dogged with troubles. Payments due from Finland do not appear. The performers start drinking again. The actor playing the Donnazza is struck down with sunstroke, and one of the Finns must return home to attend their father’s funeral. Director Corso accidently slashes his eyelid with a sharp thumbnail during an expressive flick of his hand and must conduct rehearsals with a broad bandage wrapped across his face. It is into this domain of instability that Fo and Rame return, only to ratchet up the workload.

Rehearsals begin in the morning now. However warm-hearted these people are their priorities take little account of the feelings of others. If they start once again making textual changes, the driven Finns may finally revolt.

The creative force behind Fo and Rame seems to be one of unending dissatisfaction with the status quo. There is constant tweaking, continual change.

As was to be expected Franca began immediately to amend the text of the monologue, to the silent rage of the Finns. It seems to be an involuntary process this, as natural as breathing to both of them – Dario and Franca. The trouble is that they have each his or her preferred version and depending on which of them is present at the time it is this or that which is preferred. A comedy would be played out it they were both present at the same time and proceeded to quarrel over the text.

Arturo now, after 2 weeks of directing, has to take a back seat again now, which can’t be much of a pleasure to him. I saw him and Dario engaged in what looked like a pretty furious argument, even by Italian standards of vehemence and demonstration.

To watch Franca rehearsing the Finns is a pretty amazing sight anyway. She is acting all the time, from the moment she sets foot on the stage. She acts being a director. Every movement is studied, the walk, the set of the body and head, the languor of waiting for her remarks to be translated, the elaborate patience, the sudden flow into illustrative movement, an almost numbing authoritative lowering of the voice, an unrelenting dominant grip on the proceedings.

Dario’s style is different. He is about the stage all the time, moving in his light but portly manner, breaking occasionally into an amazingly accomplished burst of mime, grammelot or stage business of some kind. Arturo sits and watches, rises and advances to explain and illustrate with his extraordinary virtuosity of gesture (il maesto dilgesto) then returning to his seat again to watch.

Over the weeks, the rehearsals drag on. But there is progress as the date of the festival draws near: Actors begin to fully inhabit their roles; the script is finalised. The show is almost ready, and it is time for Unsworth to make his exit.

Ultimately, the author is left torn between Fo the artist and Fo the man. After a month in the master’s presence, Unsworth leaves Umbria with the inklings of a new novel, an extensive first-hand account of the creative process of one of the twentieth century’s most accomplished playwrights, and a bitter postscript in his journal, written on August 16 1985, five days after the show’s premiere in Tampere:

…imbroglio after I left – the teacher of mime (a Sicilian girl) from the Little Theatre of Milan, in love with Arturo, who in addition to Alfredo has taken up with a Canadian girl – one of the students. (Alfredo himself gets interested in the girls, source of quarrel with Arturo). A party, at which everyone gets drunk and at which Sicilian girl stages dramatic scene, weeping, cursing, smashing things. It seems she gave him up after learning of Arturo’s numerous involvements with boys (Alfredo one among many) then relented – too late, because Arturo now had acquired Canadian girl.

Also disillusioning behaviour of God Dario, after Franca left he had a young girl – various young girls – on his knee, kissing and fondling in public, using position again – I mean his power. Very bad taste. He really doesn’t care much about people, not as individuals at least. Becomes gracious in presence of journalists. Then A. discovered that Sara (one of the girls working there) was actually afraid to tell him about mix up in laundry – he was wearing a tee-shirt with “Memphis” written on it, property of M. So those who work for him are frightened of him – a bad sign. And he is conscious of this and uses it.

The demarcation between artist and art will always be disputed territory. Does the strength of the work ever offset the weakness of the creator? Unsworth’s final journal entry seems rooted in disappointment that a man with as much natural talent as Fo could also be capable of such base abuses of power, all the more unfortunate given his career was built on lacerating those who deny freedom to others.

Fiasko av Dario Fo

As far as can be determined, Unsworth wrote only once for public consumption about his summer in the Umbrian hillside: a piece for the Guardian in December 1985. The article, a preview of a documentary about Fo that was screening on Channel 4 that evening, is a broadly anodyne account of the Italian master’s behaviour that month. It describes the shambles of the rehearsals, but masks Unsworth’s contemporaneously recorded opinion of Fo’s multiple shortcomings. He concludes the Guardian piece with:

It seemed to me that I had witnessed, in the Free University of Alcatraz, an exercise of power and control as unremitting as anything Elizabeth got up to. But some essential human business had been transacted there, under Fo’s benign, impatient patronage, among those hillsides. And I was glad and grateful to have seen it.

And the performance itself in Tampere? If Fo’s directing technique was confusing for the Finnish cast, the result on stage was no less confounding for Finnish theatregoers. The review in Hufvudstadsbladet, Finland’s highest circulating Swedish-language newspaper, carried the bold headline: Fiasko av Dario Fo – “Failure of Dario Fo”.

Reviewer Marten Kihlman wrote that despite high expectations for the show, the audience reception was “lukewarm”:

for my part I have to admit that none of the ten Fo plays I have seen have been nearly as cryptic and so long-winded.

Much has been written (and speculated) about Elizabeth I of England: she has been described as moody, jealous, greedy and much more. However, Fo’s portrayal of the poor Virgin Queen is unlike anything else: in the first Act she is a pathetic hysteric who regularly pees; in the second a kind of cross between Mrs Thatcher and Lady Macbeth.

Now Fo is not interested in the human Elizabeth – she simply represents Power, the given factor in an equation whose outcome is also given: power corrupts, power leads to abuse, power combined with stupidity is an abomination. All this Fo has said before, with greater concentration and sharpness.

The reviewer does dispense some praise – to the set designer.

And while he is scathing about the acting (“too loud”, “without charm”), he assigns blame in one direction only: “the ensemble should not be blamed for having a fatal theatrical ordeal: they follow Dario Fo’s directive. And even masters sometimes miss.”