Lindsay Tanner isn’t the first politician to attack the media after leaving office, and he won’t be the last.

One might say it comes with the territory; the politician’s belief that if only the media had reported his or her party/government/department more objectively, more thoroughly and fairly, with more attention to substance and policy and less to style and personality, the people would not have developed such a negative view of said party/government/department.

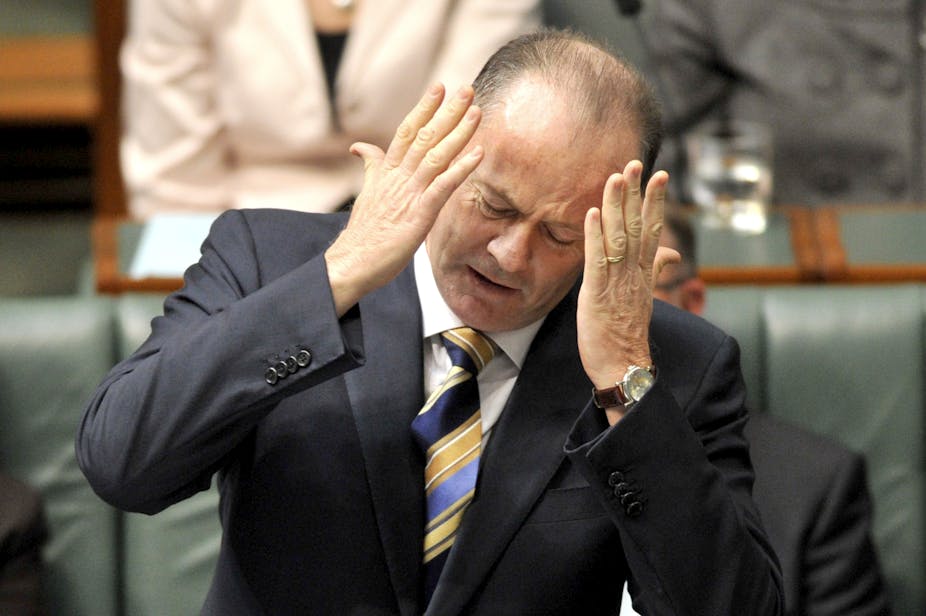

And there’s much in Tanner’s argument, as set out in his book Sideshow, and in an extensive round of media appearances in the last couple of weeks, including an appearance on Q&A, with which any reasonable observer will agree.

Politics has become a much more media-centric activity, driven by and focused on the needs and rhythms of the 24-hour, always-on, real-time news cycle.

As the quantity of news outlets to be filled with story has expanded – print, TV, radio, cable and satellite channels, now the internet, all with voracious appetites for information – politicians have had to learn how to satisfy that hunger.

Tanner writes with derision about the politicians’ “primary currency of looking like you’re doing something”, even when you’re not doing very much. He calls the unit of this currency the “announceable”.

To maintain an appearance of activity and to feed the ravenous media, governments feel obliged to serve up a stream of announceables.

The policy merit of these announcements is largely irrelevant, as long as they’re directed at tackling a perceived problem that attracts media coverage … the purpose of an announceable is to send a message, not to solve a problem.

In addition to hunger, the political media have developed a tendency to behave, as Tony Blair memorably put it on the eve of his resignation as prime minister in 2007, like a “feral beast, tearing people and reputations apart”. Political journalism is a sport of hunters, in which the politicians are prey.

Many, including some of the more thoughtful journalists, have noted the “corrosive cynicism” towards politics and the political class which sometimes seems to be the default stance of the modern media; the assumption underpinning coverage that politicians are not to be trusted, that they speak with forked tongues, that the truth is out there, but needs a shock-and-awe journalistic assault to be revealed.

“Why is that lying bastard lying to me?” is said to have been the guiding principle of one distinguished American journalist as he went in to interview politicians, and it’s not difficult to find that attitude reflected in contemporary political news – the interviewer’s contemptuous tone; the pundit’s personalized aggression.

As long ago as 1996 American journalist James Fallows coined the term “hyper-adversarialism” to describe this trend, and called for restraint and moderation from journalists in their coverage of politicians.

Not for their sake, he stressed (although we ought to remember that the great majority of serving politicians are honest, hard working public servants who deserve our respect and patience), but for the sake of democracy itself.

Lindsay Tanner correctly points out that a properly functioning democracy needs a well-informed electorate. If media audiences are consuming a diet of journalism in which politics is represented as a zero sum game where no policy statement can be taken at face value, where no politician can be trusted, who can blame them for becoming detached from the process?

In Britain in 2001, general election turnout fell to a record low of 59%. In America in 2000 it was a mere 49%. Australia’s compulsory voting system masks the extent of public apathy about politics, but few doubt that it has spread like a fungus over the body politic.

Tanner is right, too, to identify the merging of the worlds of politics and celebrity. The lines between public and private lives have been blurred in recent decades, with fewer and fewer constraints on what the media feel they are entitled to report about politicians.

Like celebrities, they are viewed as fodder for the gossip pages and the tabloid headlines. Politics has become a branch of the entertainment industry, their private affairs (in every sense) vulnerable to the shock! horror! treatment at any time.

This isn’t fair, unless of course the politician in question has made personal morality or marital fidelity, or whatever, part of his or her pitch to the electorate and can be shown to be a hypocrite. Then, and only then, should a politician’s private life become the public’s business.

So Tanner has a point, and there is value in raising the issues as he has done. Blair’s ‘feral beast’ speech ended with a call for a serious societal debate about the relationship between politics and the media.

Tanner’s intervention has a similar aim. On Q&A he acknowledged that politicians had done much to provoke the levels of public cynicism and lack of trust now displayed towards the political process.

But he wanted the media also to be required to look at their role, and to ask themselves if they were serving Australian democracy well with their focus on the “sideshow” issues such as Tony Abbott’s budgie smugglers and Julie Gillard’s voice.

I have sympathy with his plea, as a citizen with an interest in good government. But as a student of political journalism I must take issue with some of the premises of Sideshow.

First, to refer to these trends as a collective “dumbing down” of political culture – a term recurring through his argument - is no better than the lazy political journalism which seeks to reduce politics to power plays and personalities.

The people aren’t dumb, and nor are their media, most of the time. On the contrary, stories about political personality and style can be the occasion for very sophisticated debates.

Consider the case of Julie Gillard’s marital status. Did it matter to her fitness for office? Some said yes, others said no. In the end the ‘no’s carried the day, and in future women (and men) can expect their sexuality and domestic sleeping arrangements to be less of an issue than they would have been without that airing of the prime minister’s relationship.

Was it a sideshow? Yes, and no. The personal IS political, and it mattered to a lot of people that an unmarried woman should have access to the highest elected job in the land.

Many of our “human interest” news stories have this quality, of raising issues which ordinary people genuinely care about. Men in suits might not like it, but they’re not the only ones with a right to vote.

And the excesses of some journalists must be weighed against the fact that in purely quantitative terms, there is more political coverage around today, available and accessible to the average person, than there has ever has been.

More news, more analysis, more comment and opinion. Not only that, the traditional white male-dominated cliques of political journalists who set and defined news agendas in the past have been replaced by a much more diverse group, many of them operating online in blogs and publications such as this one, independent of the mainstream.

The public sphere has become denser and more diverse, more crowded with voices, and thus harder to manage for the politician.

This expansion of political media has been going on for a century, and has been the main reason for the rise of professional public relations, or spin, in the political arena.

Hawke and Keating were experts at spin, though the term was made famous by New Labour in the UK. For decades now, Australian politicians have been devoting huge resources to media and opinion management, in the hopes of securing favourable news coverage.

In return, the political journalists have become more suspicious and skeptical about the things politicians say and do. “Why is that lying bastard lying to me?” indeed.

Call it a communicative arms race, in which each new propaganda or PR trick of the politician leads to an escalation in the firepower of the political media as they seek to uncover the truth.

This, like it or not, is the name of the game in modern politics. The genie is out of the bottle, and won’t go back in.

What we, the public, want to see is honourable, ethical behaviour from both groups.