Australia is on a promise to develop a National Cultural Policy, the first since Creative Nation in 1994.

Minister for the Arts Simon Crean has released a discussion paper designed to examine how Australia can best position itself in the arts, culture and creative industries such as film and television, digital technologies and the media.

Not surprisingly, there is a huge raft of aspirations, intentions and possibilities embodied in the discussion paper and managing expectations will be, as always, a major task.

But this looks to be much more than business-as-usual in cultural policy, given what arts minister Simon Crean wants from his policy process: “‘joining the dots’, bringing culture into contact with the 'education revolution’, with technology and innovation, and with its role in binding the social fabric of the nation”.

Jobs growth

So what might a National Cultural Policy look like? For starters, I’d like to concentrate on creative careers.

At the ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative industries and Innovation, we have done detailed work on the growth in the creative workforce over the decade to 2006, based on the last three censuses that we have data from.

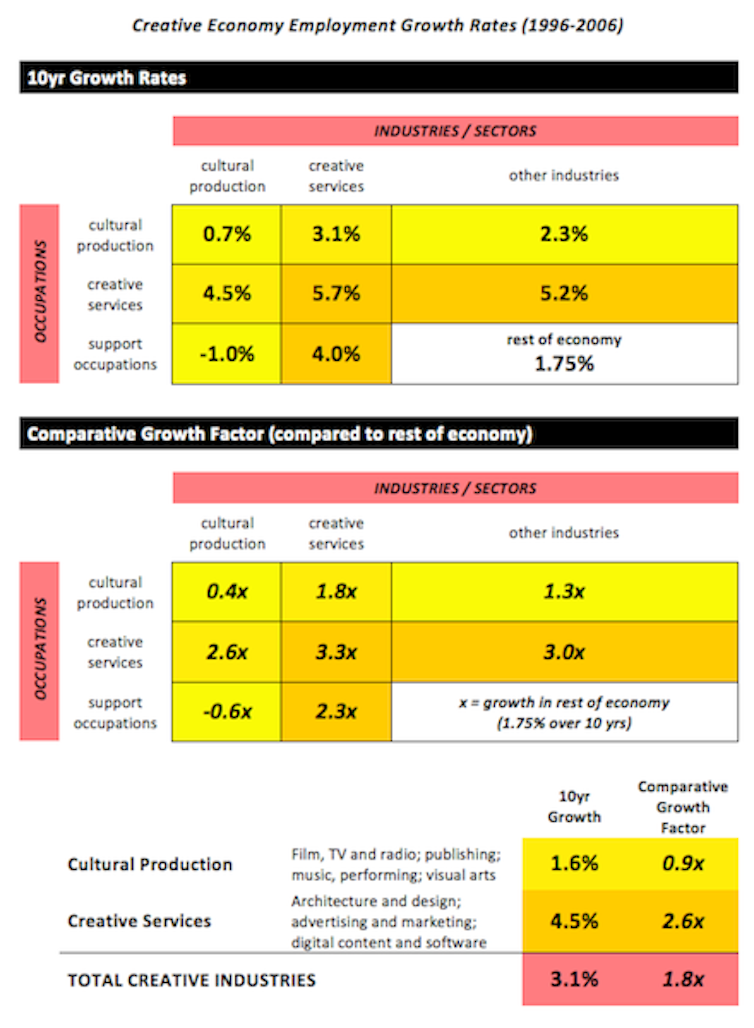

The headline data in table below provides us with stories of employment growth, plateau and sometimes decline.

The growth is found in creative services (business-to-business activities like design, architecture, digital content, software development, advertising and marketing) at around 4.5%.

That’s a plump two-and-a-half times the growth of the rest of the economy, which grew at 1.75% from 1996 to 2006.

The growth in creative services occupations (the designers, content developers, communicators and so on) is not restricted to the creative services sector itself, populated by many small-to-medium enterprises.

The growth is also found in the employment of creative occupations within other industry sectors – which we call the embedded workforce (designers employed by manufacturers, architects by construction firms, and so on).

Cultural production

It is a different story for cultural production (where the focus is on cultural products and experiences, for audiences and consumers, including film, television and radio, publishing, music, performing arts and visual arts).

The data shows us that this form of creative employment has plateaued or declined from 1996 to 2006.

Specialist film, television and radio, and publishing has plateaued, while music, performing and visual arts has declined against the national average.

The only real growth over the decade for cultural production occupations is found in employment outside of the cultural production sectors – embedded in creative service sectors (3.1% growth) and across all other industries (2.3%).

It’s true that creative careers provide much more that economic returns for the individual and the nation.

And our census data only tracks “main” jobs, and not the secondary, cash-in-hand, volunteer and amateur work that many pursue, but the employment data nonetheless offers clues for policy makers.

It suggests a need to focus on the much wider contribution that creatives are making and can make to Australia’s productivity and economic growth.

We need to ensure that we have an up-to-date picture of where creatively-minded students can find mainstream career prospects.

Challenges

But it also throws down challenges for education and training.

Are course leaders and curriculum experts across these longer term trends, and are they developing curricula that reflect them? Education and training cannot only be geared around craft skills.

Creative education and training needs to focus on the multidisciplinary challenges of fashioning sustainable careers in sectors that are more collaborative, more global, more technologically innovative and more embedded in everyday enterprise than ever before.

We need to know much more than we do about career trajectories in the creative economy. There’s almost no longer-term career tracking research of creative graduates in Australia.

The Graduate Destination Survey, conducted far too soon after graduation, is almost worse than having nothing at all, as it tiresomely reiterates the fact that graduates from the arts and humanities take longer to find their feet than those whose career paths much more tightly aligned to the established salaried professions.

The UK government’s recent Higher Education White Paper, though deeply problematic in many ways, sets out an ambitious plan for collecting and publishing data on graduate destinations in England.

We need a similar commitment in Australia – and it should come as a partnership between the education providers and the government.