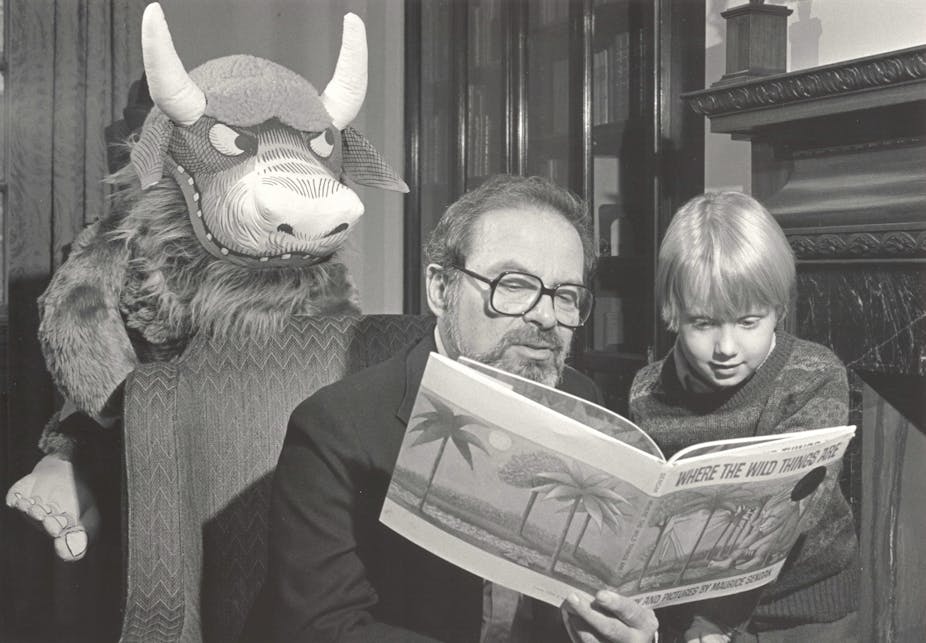

It seems we won’t be checking up on Max and the “Wild Things” any time soon. A campaign on crowdfunding website Kickstarter to fund a sequel to the late Maurice Sendak’s bestselling picture storybook Where the Wild Things Are has been shut down after Sendak’s publisher, HarperCollins, claimed copyright infringement.

Under the United States Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), HarperCollins issued a take down notice stating:

The infringing material is a proposal to create a “sequel” to Where the Wild Things Are, entitled Back to the Wild, using the characters, scenes and copyrightable elements of the original work. Any such unauthorised “sequel” would clearly violate the Estate’s right to create derivative works.

According to the aspiring author - London-based writer Geoffrey Todd - the mooted sequel would return Max and his daughter Sophie to see the Wild Things 30 years later.

Fan fiction generates heated debate. There are those authors and readers who want favourite works preserved in their original form. There are others who love to imagine continued stories. Sendak was the former. He never wrote a sequel, and once said in an interview:

People said, “why didn’t you do Wild Things 2? Wild Things 1 was such a success.” Go to hell. Go to hell. I’m not a whore. I don’t do those things.

The Sendak case raises some particularly interesting questions. The first is how a proposal can be “infringing material”, and how that judgement can be made when the sequel hasn’t been written yet and is still just a roughly sketched idea. Since the universal lynch-pin of all copyright systems is the insulation of ideas, that seems like a chilling overreach of the DMCA.

The next important issue is the territoriality of copyright law in an unbounded international book market, which makes projects like Todd’s a legal nightmare. Todd is based in the UK and obtained advice from UK lawyers that the sequel would not infringe. So why did Kickstart capitulate to HarperCollins’ take down notice?

Apart from the practical decision to avoid a legal stoush, the likely reason is a significant difference between the US and UK copyright law. US copyright owners have a very broad right “to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work”, including “a work based upon one or more pre-existing works…or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted”.

The derivative right restrained publication of 60 Years Later: Coming Through The Rye, a sequel to J.D. Salinger’s classic novel The Catcher in the Rye in 2010. It nearly did the same for Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone, a “recast” sequel to Gone With the Wind from a black slave perspective. The trial court in that case (which was overturned on appeal) said:

When the reader of Gone With the Wind turns over the last page, he may well wonder what becomes of Ms Mitchell’s beloved characters and their romantic, but tragic, world. Ms Randall has offered her vision of how to answer those unanswered questions…the right to answer those questions…however, legally belongs to Ms Mitchell’s heirs, not Ms Randall.

In contrast, the equivalent adaptation right in the UK and Australia is narrow. While it controls the right to translate novels and turn them into films and plays, it doesn’t extend to same-form adaptations “based on” earlier works. Copyright owners would have to rely on the right to reproduce a “substantial part” of a work to restrain a sequel.

The difference between the two rights is rather stark: think thou shalt not write compared to thou shalt not copy.

In the case of sequels, the reproduction right will only be infringed if too much of the original expression in the plot, scenes, dialogue or characters is taken. Geoffrey Todd’s proposed sequel to Where the Wild Things Are would necessarily use the central characters of Max and the Wild Things, but would that inevitably reproduce enough of the earlier work if it is a newly imagined sequel?

This highlights another important comparative strength of US copyright law. US courts have a history of protecting characters in isolation if they are sufficiently “delineated”. But it is unclear in both Australia and the UK whether merely using the characters would infringe the reproduction right.

Todd would be on firmer legal ground if his book was published and sold only in the UK or Australia. For those who crave literary closure and want to know what happened to the Wild Things, this is a good outcome. But for authors with a more proprietorial grip on their characters, this could point to a legal loophole which may need attention.