An increasing number of Australian parents are choosing International Baccalaureate (IB) programs over state curriculum options. This trend is particularly strong in the senior secondary years, where the IB Diploma has almost tripled in popularity since the early 2000s.

Globally, the IB is now offered in nearly 4000 schools across 148 countries. Its reach has been extended beyond the senior years to offer primary and middle years programs, and a vocational career-related certificate.

Once considered the preserve of international schools, the IB Diploma is an emerging rival to state-based certificates - such as the Higher School Certificate (HSC) in NSW and the Victoria Certificate of Education (VCE) in Victoria. The diploma is offered in a range of public and private schools.

But what is it about the IB Diploma that makes it such an alluring option to parents? And how is it different from existing state-based curricula and certificates?

The global certificate

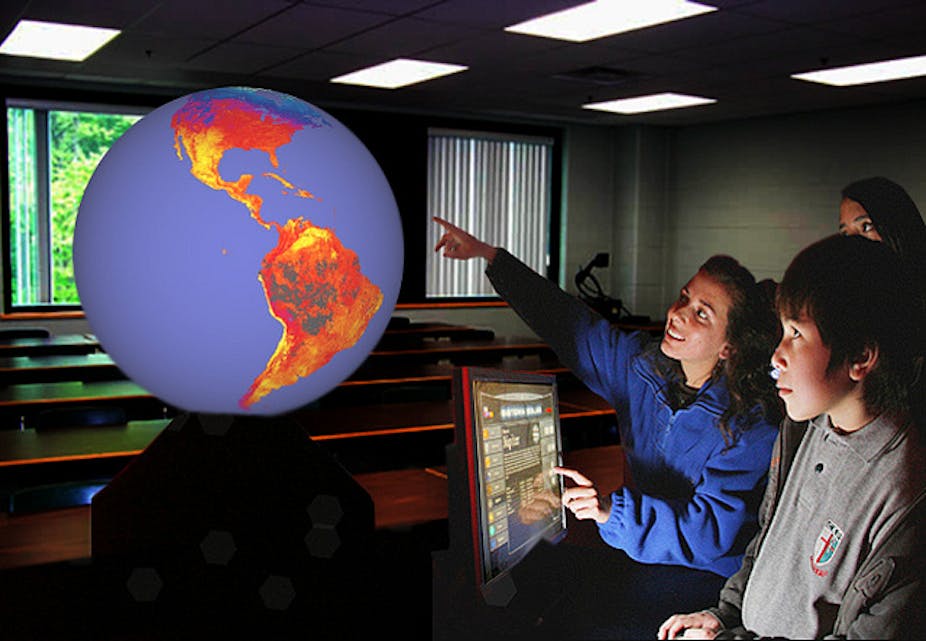

The global nature of the IB Diploma has always been a key feature. This no doubt is appealing to parents who are keen to prepare their children for participation in global education and job markets.

The IB was established in Geneva in 1968, with the aim of developing “international mindedness” in students. The current aim of the IB Diploma is to prepare students for

effective participation in a rapidly evolving and increasingly global society.

As globalisation has intensified, the IB Diploma is increasingly seen as a university preparation program catering for mobile and transnational young people.

In Australia, many private schools have adopted the IB Diploma program. They often sell it to parents and students as a more robust and superior pathway to university.

Of course, the domination of Australian private schools in the provision of the IB has fuelled perceptions that it is an elite and exclusive curriculum. Globally, however, this is not the case. Public schools offer more than half of all IB programs, particularly in the USA.

Curriculum breadth

The IB Diploma has a unique curriculum, with several features that distinguish it from state-based senior certificates.

To begin with, its curriculum emphasises academic breadth over specialisation. Students are required to study one subject from each of the following five groups:

- Language and literature

- Language acquisition (a second language)

- Individuals and societies

- Sciences

- Mathematics

Students can then elect to do a sixth subject from the Arts, or take another subject from the first five groups.

The academic curriculum is accompanied by The Learner Profile. This outlines a set of ten learning attributes that the IB organisation suggests are central to building internationally -minded people.

The IB’s emphasis on academic breadth and its requirement of a second language could be seen as both a blessing and a curse. On the positive side, a second language is likely to make students more competitive in global job markets and the emphasis on breadth will keep their post-school options open by ensuring they remain academic “all-rounders”.

On the downside, some might view the language requirement as unnecessarily onerous, and the emphasis on breadth as discouraging the specialisation that many state-based certificates allow for students who want to tailor their senior years towards preferred subject areas.

Since the 1990s, Australian state-based certificates have also seen a rapid increase in vocational education and training options. All certificates now allow students to integrate vocational training into their senior years.

The IB Diploma, however, remains academically focused and does not allow for the integration of vocational subjects. For students who wish to pursue vocational pathways, the IB has recently created the IB Career-related Certificate. There is, however, currently only one provider in Australia.

Core requirements

In addition to its focus on breadth, the IB Diploma has three “core requirements”.

First is the “Extended Essay”. This requires students to undertake research in an area of personal interest, working with an “academic supervisor” (usually a teacher in their school) to produce a 4000-word written piece.

Second is the core subject “Theory of knowledge”. This engages students in theoretical reflections on the nature of knowledge, with a particular focus on how evidence is gathered and used in contemporary contexts.

Third is a core subject called “Creativity, Action, Service”. This requires students to engage in a range of creative arts-based, physical and service-learning activities.

The Extended Essay and Theory of Knowledge are both highly academic and can be seen as providing a segue from the senior secondary years to university study.

These requirements might be appealing to parents who want their children to arrive at university with an advantage over others. There is some evidence to suggest this might be the case. The IB organisation, for example, has compiled summaries of research (see here and here) suggesting students who take the diploma achieve higher results at university and have better post-university employment outcomes.

Looking to the future?

As the cultural and economic realities of globalisation deepen, new curricula will be required that extend beyond the traditional concerns of nations.

While national and local factors clearly remain important, curricula will need to pay greater attention to looking forwards and outwards, to cater for an increasing number of transnational families and young people.

In Australia, the future of state-based senior certificates hinges largely on whether or not the national Australian Curriculum is extended into the senior years, as was originally planned. The option of a future national certificate is not out of the question.

In the meantime, the trajectory of change suggests parents will continue to vote with their feet and overlook state options in favour of “global alternatives” like the IB.