The downing of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 has considerably increased the strain on the relationship between Russia and the European Union and United States on the other side.

Following the escalation of the Ukrainian crisis earlier this year, the EU and US had already adopted some “phase two” sanctions, including travel bans and some asset freezes affecting Russian individuals and companies. Russia was also suspended from the G8, whose summit should have taken place in Sochi in June.

The scope of “phase two” sanctions is now being expanded, although the European Union has rejected the push for so-called “phase three” sanctions directed at entire sectors of the Russian economy, for now at least.

Australia has also taken a firm stance against Russia, with foreign minister Julie Bishop succeeding in obtaining a unanimous resolution at the UN Security Council (including permanent member Russia) condemning the downing of the flight and demanding an international, independent investigation.

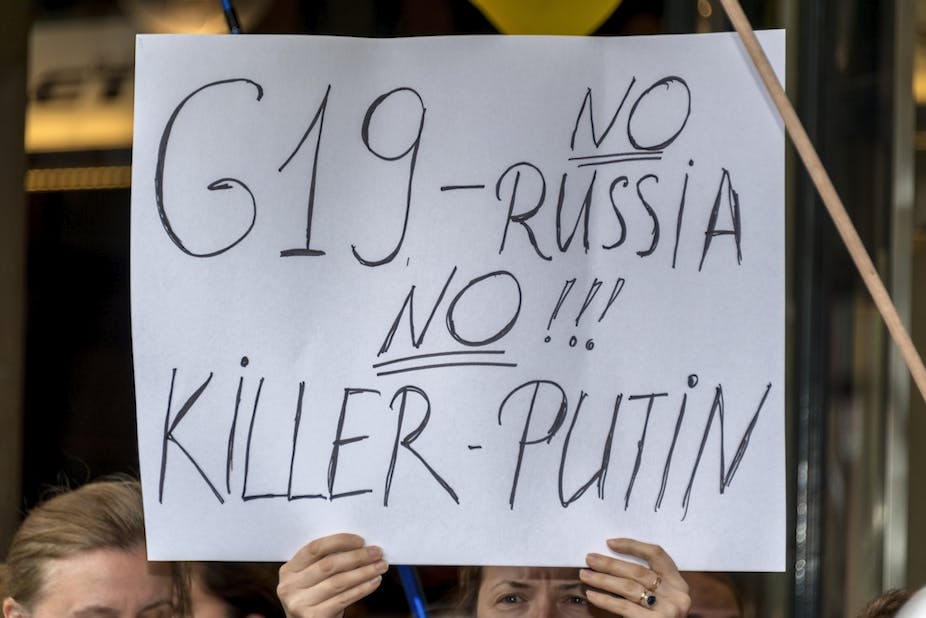

Even before the plane disaster, there were suggestions that as host of the G20, Australia could possibly remove Russia from the G20 Summit in November. These suggestions are now stronger than ever.

Asked whether this might effectively happen, Prime Minister Tony Abbott replied that he would “… wait and see what will happen” and that:

we want to ensure that visitors to this country have a good will to this country, visitors to this country are people who have done the right thing by this country.

In a meeting with Russian’s trade minister, Abbott went further, saying:

Australia takes a very dim view of countries which facilitate the killing of Australians, as you would expect us to.

Abbott spoke directly with Russian President Vladimir Putin before the approval of the Security Council resolution, but clearly the tension between the two countries remains high.

A unanimous decision made by 19 members of the G20 to remove Russia from the summit would certainly have a significant impact. It would mean that there is a strong, compact anti-Russian coalition capable of enforcing tough sanctions, which extend well above and beyond asset freezes and travel bans (which are standard “phase two” sanctions).

The economic threat for Russia would be credible and would come at a time when its economy is particularly fragile. In 2014 only, some US$75 billion worth of capital has fled Russia. The rate of economic growth decreased to less than 1.5% in 2013 and it is now close to zero.

With the country on the edge of a recession, the prospect of very harsh sanctions sustained by all the largest countries in the world might be enough to convince Russia to change its approach to the Ukrainian situation.

But this is simply not going to happen. At this stage, it seems very unlikely, if not impossible, that all 19 other members of the G20 could agree on excluding Russia from the summit.

When the hypothesis of exclusion first circulated earlier this year, China, India and Brazil issued a statement warning of their concern about Australia’s intention. Only a few days ago, Mexico stressed that blocking anyone from the G20 would be bad for the group.

The European front is also not necessarily unanimous. Countries like Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, which heavily depend on Russian energy exports, might be less willing to ramp up sanctions against the Russian energy sector. France currently has a $1.6 billion contract to sell military helicopters to Russia and might be therefore less prepared to support sanctions that involve an arms embargo.

Given this situation, it might not be a good idea for Australia to insist on excluding Russia. Certainly, as a sovereign state, Australia has the right to deny access to any undesired person, including eventually President Putin and the Russian delegation.

But such a unilateral action would almost certainly split the G20 and lead to its collapse. This would be a real loss for the global community.

Over the past few years, the G20 has proved to be a useful mechanism for coordinating economic policy in response to global shocks. Its demise would make macroeconomic cooperation more difficult, with adverse effects for all countries.

Moreover, the G20 is an open channel of communication between Russia and the rest of the world. Shutting it down would only make the dialogue more difficult, with the risk of returning to a Cold War situation.

Conversely, by bringing leaders together, the summit could create an opportunity to engage in diplomatic negotiations. Something like that already happened last year, when the St Petersburg summit provided the context for addressing the Syrian situation.

All in all, while the strong rhetoric of Abbott and the Australian government is understandable, using the G20 to take an adversarial stance against Russia is likely to do more harm than good. It is instead within the UN Security Council that strong action should be taken to ensure a peaceful solution to the Ukrainian crisis.