Marthe Bonnard is a perpetual presence throughout the artist Pierre Bonnard’s work. From his early illustrations in the 1890s to his last luminous canvases of the 1940s, she is the subject of hundreds if not thousands of paintings and drawings. Yet art history has long been unkind to Marthe.

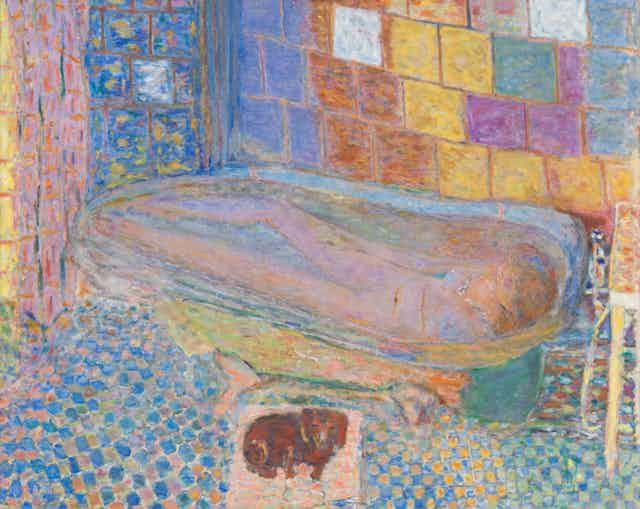

Bonnard’s lustrous baignoires are believed to reflect her neurotic obsession with bathing, while his supposedly reclusive life in the south of France in the 1920s is usually explained by Marthe’s reputed paranoia and hatred of other people. In more recent decades, their relationship has been the subject of exhibition catalogues, novels, and a lot of journalism. With every exhibition of his work, similar headlines appear: “In the bath with Mrs Bonnard: how the painter’s difficult marriage inspired his spellbinding art.”

But, having spent many years researching Bonnard, I have found that much of what is believed about Marthe may be false. New evidence in the Burlington Magazine reveals that she married another man, while further research suggests how bias and prejudice have distorted Marthe’s reputation.

Unseen documents

The widely told story of Marthe’s life is that of a young woman working in a fancy artificial flower shop in fin-de-siècle Paris, who in 1893 met a bourgeois bohemian artist on the street. She would supposedly become his constant muse until her death in 1942.

She is said to have lied in introducing herself, claiming to be an orphan of noble Italian heritage called Marthe de Méligny, when her real name was Maria Boursin. As time wore on, the woman known as Marthe supposedly became increasingly neurotic, demanding, paranoid and anti-social, dragging Bonnard to spa resorts and away from Paris.

In 1925, the pair married, but apparently only because the jealous Marthe wished to prevent the artist from marrying the woman he passionately loved, Renée Monchaty, by forcing him to wed her instead. Monchaty reputedly killed herself as a result.

Bonnard’s muse, so the story goes, was also his jailer.

After contacting archivist Pierre Allart, and working from his tip-offs, I have uncovered documents that suggest an entirely different shape to Marthe’s life. They show, first, that Marthe was not the ever-constant model that has always been imagined.

In 1899, on her brother’s death certificate, she signed herself as the wife of a Monsieur Renard and gave an address not connected to Bonnard. Who Monsieur Renard was, however, remains an enigma. Despite our extensive searches, no further documents have emerged that place him in the picture. Nor, though, has anything to contradict Marthe’s assertion.

Marthe met Bonnard in 1893, and is at the centre of his work until around the time she signs herself as married in 1899 (when she appears to disappear for a while before gradually coming back). We do not know what caused the pair to split, but certainly the hard conditions of life for women in Marthe’s position left her at the mercy of proposals. And Bonnard, although from a bourgeois background, would not have earned much during the 1890s from his fledgling artistic career producing book illustrations and posters. In 1899, he was living in apartment 12, on the fifth floor of 65 rue Douai, not far from Montmartre – then a rather seedy district of Paris.

Working class woman

In light of this finding, certain matters suddenly make sense: that same year, Bonnard started work on a self-portrait with Marthe, titled Man and Woman, in which the space between the pair is dramatically split by a screen. This puzzling painting now has an explanation. Other issues that have never been noticed before suddenly grow salient: like the fact that Marthe seems to all but vanish from Bonnard’s work for a period of several years.

Some of Bonnard’s erotic illustrations, for which Marthe posed around 1897, were for the book Marie by Peter Nansen, which bears a certain parallel to Marthe and Bonnard’s own relationship.

In the story, the bourgeois narrator falls in love with an innocent working-class woman called Marie – depicted in the book with pictures of Marthe. After a time, Marie disappears, and becomes engaged to a wealthy manufacturer, until she eventually re-emerges and happily marries the narrator. Sound familiar? Perhaps this is why The Window, which Bonnard painted that year, depicts a copy of Nansen’s book.

Other newly discovered documents also reveal Marthe’s early life of provincial poverty. Born as Maria Boursin, her childhood was marked by the death of her father and one of her sisters. In her late teens, her mother, a seamstress, moved with her children to the northern edge of Paris. Here, Marthe lost another sister, Aline, who had been working as a “fleuriste” – possibly an artificial flower maker working long factory hours for pitiable pay.

As for Marthe herself, decades later Bonnard’s nephews claimed that she was selling artificial flowers at the time she met Bonnard. Yet this claim could well be an embellishment. It is possible that Marthe was also a labourer making artificial flowers, which could well explain her later respiratory problems. Either way, she would have earned barely enough to get by.

Legal disputes

These findings give us a new insight into Marthe’s later troubled mental health, or what Bonnard once called “the phobias in her head”, that seemingly developed as her physical health deteriorated in her early sixties. Her early life was one that most of Bonnard’s bourgeois family and friends would never understand. Many of them found her “cheap finery” and her “savage harsh voice” amusing and strange.

So it is unsurprising that Marthe no longer wanted “to see anyone anymore, not even her old friends”, as Bonnard apologetically explained in a letter to Berthe Signac, the painter Paul Signac’s wife, in 1932. In fact, after a lifetime of being drawn in the nude and having her naked body rendered in life-sized paintings for increasingly large audiences, such feelings seem understandable. They are certainly not a sure sign of pathological paranoia.

Crucially, Bonnard’s own letters suggest that Marthe’s troubles and her need for “complete solitude”, did not arise until the final decade of her life. This was several years after he started painting her lying in the bath.

So how has Marthe’s suffering come, in the decades after her death, to define her character, and to be stressed as a crucial explanation for Bonnard’s late oeuvre from the 1920s onwards?

From the 1950s, a small group of members of Bonnard’s family and close friends offered accounts of the artist’s life that repeatedly described Marthe as deeply strange, neurotic and unwell. In their accounts, Marthe’s problems do not arise only in her late sixties but seem to define her character more generally. Yet much of this established testimony came from individuals who benefited from such tales.

The stories began to emerge in a torturous legal dispute over the artist’s estate following his death. In 1951, Bonnard was found posthumously guilty of having forged Marthe’s will, a verdict that required Bonnard’s family to turn over half of the estate, including 700 works, to Marthe’s heirs. The family subsequently made a successful appeal. Their appeal turned on the claim that Bonnard had been unaware of Marthe’s family, and therefore must have believed his forgery was a victimless crime.

To win back their vast inheritance, the family had to establish that Marthe was cagey and secretive about her family, even with her own husband. They insisted that in a relationship of 50 years, Marthe’s illness was such that she likely never let Bonnard know that she had nieces – including the “petite Gabrielle”, to whom Marthe used to write cheery postcards.

The case itself is the first appearance, to my knowledge, of the intriguing story that Marthe first introduced herself to Bonnard with the fictitious name of de Méligny and a false story about being an orphan. The party appealing also insisted in the trial on Marthe’s “mental derangement”. Over the years and decades that followed, those who were partisan in its proceedings have written numerous accounts of Marthe, continuing to describe her as neurotic, secretive and paranoid – accounts that have been taken at face value ever since.

Differing accounts

Some of the popular stories about Bonnard’s relationships have unravelled before.

In 1998, the art historian Nicholas Watkins showed that the artist’s nephews and friends had offered various incompatible accounts of the suicide of Bonnard’s lover Monchaty, all of which contradicted the details on her death certificate. Contrary to stories about Monchaty’s dying in a bathtub in Rome, or in a Paris hotel after filling her bed with white lilacs, her death certificate showed that she had simply died at home (it did not specify the cause).

Moreover, Monchaty’s death could not have prompted Bonnard’s marriage to Marthe, as had previously been claimed: it occurred almost a month afterwards. In response, art historians simply tweaked the story, claiming that Monchaty killed herself in response to Marthe and Bonnard’s marriage.

Instead, bigger questions ought to be raised: if the mode, place and time of Monchaty’s death were fabricated, what else should we also be willing to treat as an unreliable rumour?

The archival sources relating to Marthe’s life and her first marriage may be new discoveries, but an awareness of bias in the testimony against her has long been available to anyone willing to see it. So why did it remain unseen? Surely because the stories the art world have preferred to recycle – about a deeply secretive and strange woman turning hysterical and difficult in middle age – are stories that ultimately satisfy the deeply held prejudices of viewers, or at the very least match unconscious expectations.

I wonder, too, if believing that Marthe was mad somehow dispels the unease we might otherwise feel in paying to look at painting after painting of her, as she goes about her most intimate daily routines. Perhaps we feel less uncomfortable about Bonnard’s apparently invasive, constant access to her daily life if we can diminish her individuality, and reduce Bonnard’s iridescent and complex paintings into metaphors of her decline.

Visiting a Bonnard exhibition needn’t be a guilt trip. But we might acknowledge that, as his model, Marthe played a role in his artistic success. And that, like one of his paintings, the rich layers of her life extend beyond what is visible on the surface.