Every year, on September 27, the global tourism community celebrates World Tourism Day. This year’s theme is about community development and how tourism can contribute to empowering people and improve socio-economic conditions in local communities.

But who are the people who might visit “communities” and what does it mean – these days – to be a tourist?

There are many tourist stereotypes – an overweight Westerner in shorts with a camera dangling around their neck, or maybe a trekking-shoed backpacker hanging out in the Himalayas. Many people think of “tourism” and “holidays” as distinct times of the year when the family travels to the seaside or the mountains.

World Tourism Day is an opportunity to discuss how much more encompassing the phenomenon of tourism is than most people might think.

What is a tourist?

People are more often a “tourist” than they realise. The United Nations World Tourism Organisation broadly defines a tourist as anyone travelling away from home for more than one night and less than one year. So, mobility is at the core of tourism.

In Australia, for example, in 2013 75.8 million people travelled domestically for an overnight trip – spending 283 million visitor nights and $51.5 billion.

Reasons for travel are manifold and not restricted to holidays, which makes up only 47% of all domestic trips in Australia. Other reasons include participation in sport events, visiting a friend or relative, or business meetings.

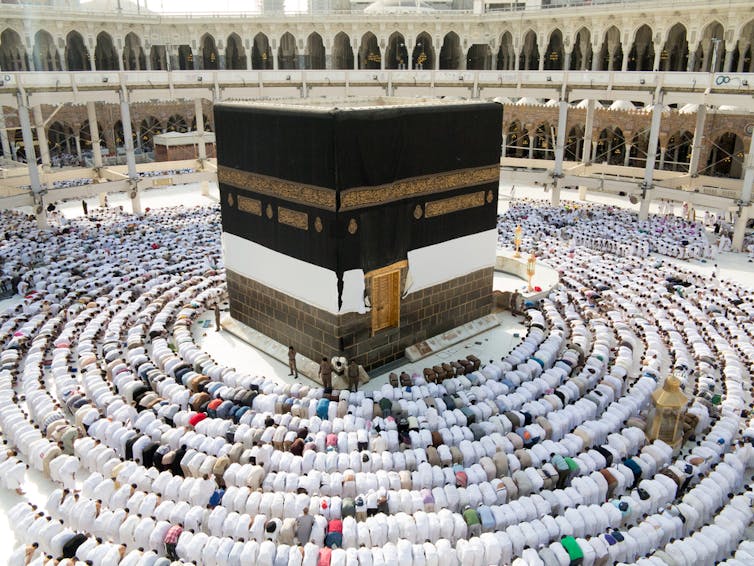

Some of the most-visited destinations in the world are not related to leisure but to other purposes. For example, pilgramage tourism to Mecca (Saudi Arabia) triples the population from its normal 2 million during the Hajj period every year.

Travel, work and leisure: what’s the difference?

Tourists are not what they used to be. One of the most pervasive changes in the structure of modern life is the crumbling divide between the spheres of work and life. This is no more obvious than in relation to travel. Let me test the readers of The Conversation: who is checking their work emails while on holiday?

A recent survey undertaken in the US showed that 44.8% of respondents check their work email at least once a day outside work hours. Further, 29.8% of respondents use their work email for personal purposes.

Post-modern thinkers have long pointed to processes where work becomes leisure and leisure cannot be separated from work anymore. Ever-increasing mobility means the tourist and the non-tourist become more and more alike.

The classic work-leisure divide becomes particularly fluid for those who frequently engage in travel, for example to attend business meetings or conferences. Conferences are often held at interesting locations, inviting longer stays and recreational activities not only for participants but also for spouses and family.

Further, city business hotels increasingly resemble tourist resorts: both have extensive recreational facilities such as swimming pools and spas, multiple restaurants and often shopping opportunities (e.g. Marina Bay Sands, Singapore). And, of course, they offer internet access – to be connected to both work and private “business”.

Understanding how people negotiate this liquidity while travelling provides interesting insights into much broader societal changes in terms of how people organise their lives.

For some entrepreneurial destinations these trends have provided an opportunity; namely the designation of so-called dead zones – areas where no mobile phone and no internet access are available. Here the tourist can fully immerse in the real locality of their stay.

Fear of missing out

The perceived need to connect virtually to “friends” (e.g. on Facebook) and colleagues has attracted substantial psychological research interest, with new terms being coined such as FOMO (fear of missing out) addiction, or internet addiction disorder.

A recent Facebook survey found that this social media outlet owes much of its popularity to travel – 42% of stories shared related to travel. The motivations for engaging in extensive social media use and implications for tourism marketing are an active area of tourism research.

Thus, understanding why and what people share while travelling (i.e. away from loved ones, but possibly earning important “social status” points) might provide important insights into wider questions of social networks and identity formation, especially among younger people.

Tourism and emigration

The increasingly global nature of networks has been discussed in detail by sociologist John Urry and others. They note the growing interconnectedness between tourism and migration, where families are spread over the globe and (cheap) air travel enables social networks to connect regularly.

As a result, for many people local communities have given way to global communities, with important implications for people’s “sense of place” and resilience. The global nature of personal networks extends to business relationships where the degree to which one is globally connected determines one’s “network capital”.

Urry also noted that mobility has become a differentiation factor between the “haves” and “have nots”, with a small elite of hypermobile “connectors”. Thus travel and tourism sit at the core of a potentially new structure of leaders and influential decision makers.

The global ‘share economy’

Engaging in this global community of tourists is not restricted to those who travel actively. The so-called Share Economy, where people rent out their private homes (e.g. AirBnB), share taxi rides or dinners, has brought tourism right into the living rooms of those who wish to engage with people who they may not meet otherwise.

Potentially this parallel “tourism industry” provides a unique opportunity for bringing people together and achieving peace through tourism (see International Institute for Peace through Tourism). A whole new area for research travellers, “guests and hosts” and their economic impacts, is emerging.

In a nutshell, tourism is much more than the service industry it is usually recognised for, both in practice and as a field of academic enquiry. Tourism and the evolving nature of travellers provide important insights into societal changes, challenges and opportunities. Engaging with tourism and travel also provides us with an excellent opportunity to better understand trends that might foster or impede sustainable development more broadly.