2012 will be a critical time in our development as a nation with huge uncertainties in many areas both in Australia and globally.

Over more than ten years we have lived through a remarkable mining boom, giving us a huge opportunity to enhance national wealth, but not forcing hard decisions of the kind which led to the great reforms of the Hawke-Keating years.

These had bipartisan support from an opposition also committed to major economic and social reform. Sadly there is no sense of such common purpose in Canberra today despite so many uncertainties in the world, including big changes with the rise of China, India and Indonesia, let alone many other uncertainties in the environment in which we must function as a nation.

Short term view no long term strategy

The boom allowed us to weather the Asian economic crisis of 1997 and to withstand the potentially dire consequences of the Global Financial Crisis. We are now, very properly, trying to get our national accounts back in order after heavy expenditure to avoid a profound recession in 2008-2010 – a crisis which is still causing huge problems in Europe, the US and elsewhere.

When we ask ourselves where we need to go as a nation over the next ten to 20 years, our national political leaders on either side of politics seem either to be short of ideas, or too preoccupied with the short-term, with opinion polls, focus groups or immediate issues of political advantage. We badly need appropriate leadership from both sides of the political arena if, as a nation, we are to make the necessary moves to secure our long-term future in a fast changing world.

Dealing with the big issues

We have historically depended on Britain and then Europe and the US for our economic and cultural development with our high performers going overseas to achieve careers of great distinction.

Whilst we do indeed need to mix and compete on the world scene, it is time we shed our “cultural cringe” and backed our own development as Australia. This necessitates the relative degree of investment in education and in research and research infrastructure that nations with similar aspirations make. The present Government has done a great deal in education in positive terms with implementation of many “Bradley” recommendations.

The just released Lomax-Smith report argues in a nuanced way for modest increases in funding for education in areas currently underdone. An additional need is for a more robust base for university base research/innovation funding to cover core salary costs not funded in grants. This may be difficult to fully meet in constrained times but political endorsement and delivery in a pragmatic timeframe would be a great investment in Australia’s future.

Realigning to Asia

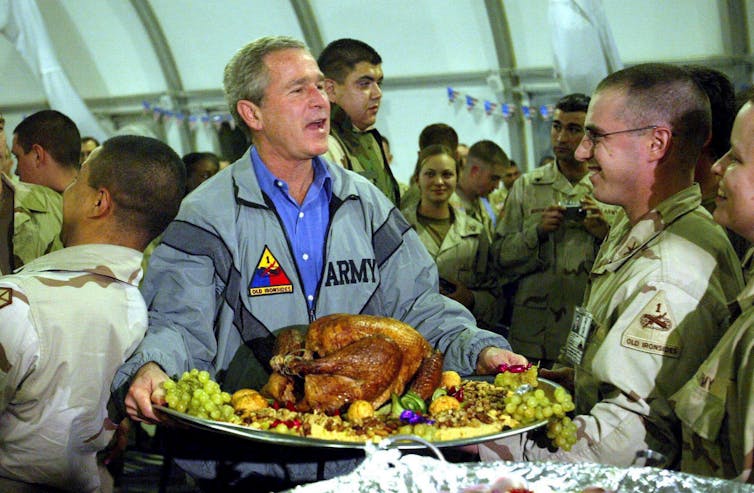

We have, since WW2, seen alliance with the US as our prime source of protection, as was proved against Japanese imperialism. However, continuing to tie ourselves to its coat-tails makes no sense if it continues to behave as the only world super-power and ploughs huge resources into military adventures such as the second Iraq War and Afghanistan to the point where its accounts are almost bankrupt (made worse by George Bush’s passion for reducing taxation for the wealthy).

We may witness its relative decline as an economic power with inevitable consequences for future roles: military, diplomatic and political. China is already the second largest world economy and will inevitably overtake the US in such terms. We need to stand on our own feet. We must maintain our excellent relationships with the US and UK but also ensure strong links with China and India. It will not be enough to say our soul mate is the US as we trade with China. We need to reach a more nuanced position and in doing so help build bridges between the world’s great powers.

As a nation we are singularly fortunate in being strategically close to Asia and having well developed coal and mineral resources which, for some years, they will be keen to access. However, prices will inevitably decline as other international competitors develop, and demand will stabilize as needs are met. This simply means we have time to get our act together to create a base for a sustainable competitive future building on other strengths. Now is the time to start.

Identifying our strengths

The man or woman on the street would probably nominate sporting achievements. We put great store by our Olympic performances and international standing in many competitive sports. Despite government decisions to fund many promising athletes, this endeavour will never be a base for international economic or cultural leadership.

We certainly have a stable society and democracy, well-established finance and business institutions, many strong and vigorous universities, CSIRO and other research institutes, good cultural institutions and a reasonably well functioning health care system. All these are attractive to our Asian neighbours, whose societies are still evolving. Can we not build on these?

We are a multicultural society following huge and varied immigration since WW2 and later the ending of the White Australia Policy. However we have, as a nation, neglected education in foreign languages, so we lack a natural understanding of the problems faced by foreign visitors, or the capacity to deal directly when engaging in commerce in other countries.

We need to make the most of our cultural diversity and add to this strength by enhancing teaching of foreign languages and developing cultural understanding, particularly of our Asian neighbours. Our education system needs specific support to achieve these goals, but this is but part of the challenge. More children in our school system should learn Mandarin or Japanese. European languages, our mainstay for decades, should be de-emphasised even more than they have been. University policies to encourage international experience, especially in Asia, should be strengthened. In parallel scientific literacy, which is strong in many Asian school systems, should be systematically enhanced.

Can we learn from other nations which transformed themselves?

The Prussian state was all but destroyed by Napoleon’s armies between 1801 and 1806 but a group of far sighted Prussian thinkers saw university education, linked with research, as the answer to rebuilding. William von Humboldt founded the University of Berlin in 1809 and others followed in other German states. They became a powerhouse of discovery, with their new PhD degrees and engineering schools from which innovative industrialisation developed. It led, in due course, to the Prussian Customs Union from which Bismark created a new powerful German nation, fast usurping European leadership from Paris and Vienna.

The US was developing vigorously at the time, but it found large numbers of its most able young university graduates going to Germany to study as PhD students. A new Johns Hopkins University was created on the Berlin model in 1893 and rapidly thereafter all the major US universities adopted the model with vigorous research based graduate schools reaching out to the professions and industry to change the nation. With further investment in research largely channeled through universities, following the economic draining of reserves in WW2, US innovation led the world through the balance of that Century.

Japan also invested heavily in research and innovation, especially applying automation in manufacturing as it recovered from defeat, but in recent years has been held back by a stagnant economy. Sadly with its huge deficit problems, the US is now cutting back on government investment in research. We have a vigorous research base in our universities struggling to achieve outcomes with vastly less resources per head of population than most of our competitors.

Whilst almost all OECD countries were ploughing increased resources into universities, most strikingly in Asia, Australia has been progressively reducing funding per student since 1990 under governments of either political persuasion. To give Governments their due, crucial investments in national research infrastructure have been made. One that stands out is the Australian Synchrotron, a massive investment that in a way exemplifies Australia’s evolution into a high-tech clever nation. Ongoing national commitment to these programs is absolutely crucial.

What must be done?

Of course it is not easy at the present time to transfer major resources to universities when reduced expenditure is the priority for governments, but there are things that can be done. Since the days of the Dawkins reforms of 1989- 1993 there has been an increase in central control of all universities, with institutions required to provide detailed returns to Canberra on staff, students and all programs as if central control was the answer to delivering quality outcomes in education and research.

Clearly university accreditation and some regulation is essential, but ideally in a light touch framework. The new TEQSA agency has been established in a framework of university self-accreditation and it is crucial that as it commences it does not develop undue red tape or diminish innovation and creativity. Current indications are positive in this regard.

Let the invisible hand decide

The market is a safer way to ensure universities are meeting the needs of the community than are government officers, no matter how conscientious. Repeated reviews in 1992, 1998-9 and 2008 have all made the case.

The latest, by Bradley, is set to be implemented to a considerable degree in coming years. However, is it vital that the dead hand of government control and oversight be kept to an appropriate level to allow universities to use their resources in meeting the needs of students, not primarily in satisfying bureaucrats.

All vigorous university systems reflect civic institutions with a high degree of autonomy. Where universities become branches of Government departments they are diminished. Australian universities have and should continue to have close State as well as Federal Government links but be embraced as independent pillars of a civic society.

Research infrastructure funding for national platforms has been a plus in recent years. It is crucial that this is maintained even in constrained times or national innovation and productivity will be lessened by a major own goal. With centralisation of tertiary university education and research into a new ministry under a vigorous minister there is an opportunity to make real headway in the next few years.

Australia’s future depends fundamentally on investing in the potential of a younger generation in research and innovation, which then extends into every branch of our society. Commitments to research and research training are both vital elements. This is where we must invest to secure our place in a fast changing world.