With the global spread of the new coronavirus, fears about illness and death weigh heavily on the minds of many.

Such fears can often result in a disregard for the welfare of others. All over the world, for example, essential items such as toilet paper and hand sanitizer have been sold out, with many people stockpiling them.

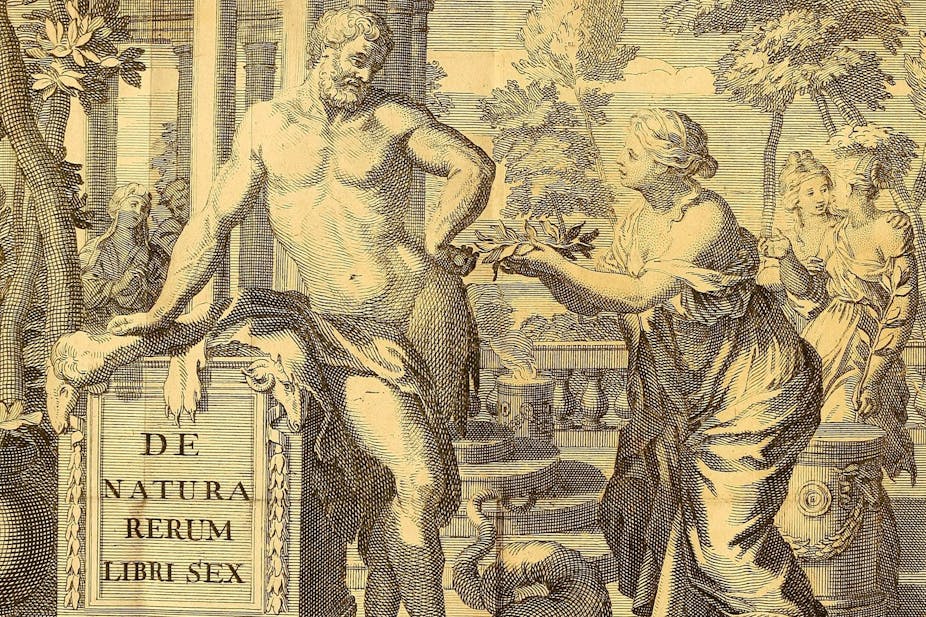

A first-century B.C. Roman poet and philosopher, Lucretius was worried that our fear of death could lead to irrational beliefs and actions that could harm society. As a philosopher who has just published a book on Lucretius’ ethical theory, I cannot help but notice how his predictions have come true.

Lucretius and his beliefs

Lucretius was a materialist who did not believe in gods or souls. He thought that all of nature was made of continually changing matter.

Since nothing in nature is static, everything eventually passes away. Death, for Lucretius, allowed for new life to emerge from the old.

When there is no immediate danger of dying, people are less afraid of death, Lucretius says in “The Nature of Things.” But when illness or danger strike, people get scared and begin to think of what comes after death.

Some people might make themselves feel better by imagining that they have immaterial souls that shed their bodies or that there is a benevolent God, Lucretius writes. Others might imagine an eternal afterlife, as the philosopher Todd May argues in his 2014 book, “Death.”

The fear of death may lead people to seek comfort in the idea that there is an immortal soul that is more important than the body and the material world.

Fear and social divisions

However, an ethical danger of such beliefs, Lucretius argues, is that people may become preoccupied with something that literally does not matter at all.

This fear and anxiety, Lucretius says, stains everything in life. It “leaves no pleasure clear and pure” and it could even lead to “a great hatred of life.” Studies show that anxiety about death can lower one’s immune system and make it more vulnerable to infections.

Additionally, Lucretius says, the fear of death can also lead people to create social divisions. When people are afraid of dying, they might think that withdrawing from others will help keep danger, disease and death away.

“This is why people, attacked by false fears, desire to escape far away and to withdraw themselves,” Lucretius says.

This phenomenon is well documented in terror management studies. The fear of death results in a desire to escape from disadvantaged groups.

In China, for example, rural migrant workers were blocked from quarantined cities, kicked out of apartments and turned away by factory owners, as authorities tried to control the spread of the coronavirus.

In the U.S., poorer workers do not have the luxury to work from home when schools close, and cannot afford to take sick days or see a doctor. They are thus more vulnerable compared to those who can afford to isolate themselves.

Asian Americans are also experiencing increased discrimination following the coronavirus spread. Fewer people are going to Chinese restaurants out of fear of being infected. Asian American schoolchildren too have been targets of racist comments.

Focus on staying healthy

The fear of death is irrational, according to Lucretius, because once people die they will not be sad, judged by gods or pity their family; they will not be anything at all. “Death is nothing to us,” he says.

Not fearing death is easier said than done. That is why, for Lucretius, it is the most important ethical challenge of our life.

Instead of worrying about what may happen after death, Lucretius advises people to focus on keeping their bodies healthy and helping others do the same.