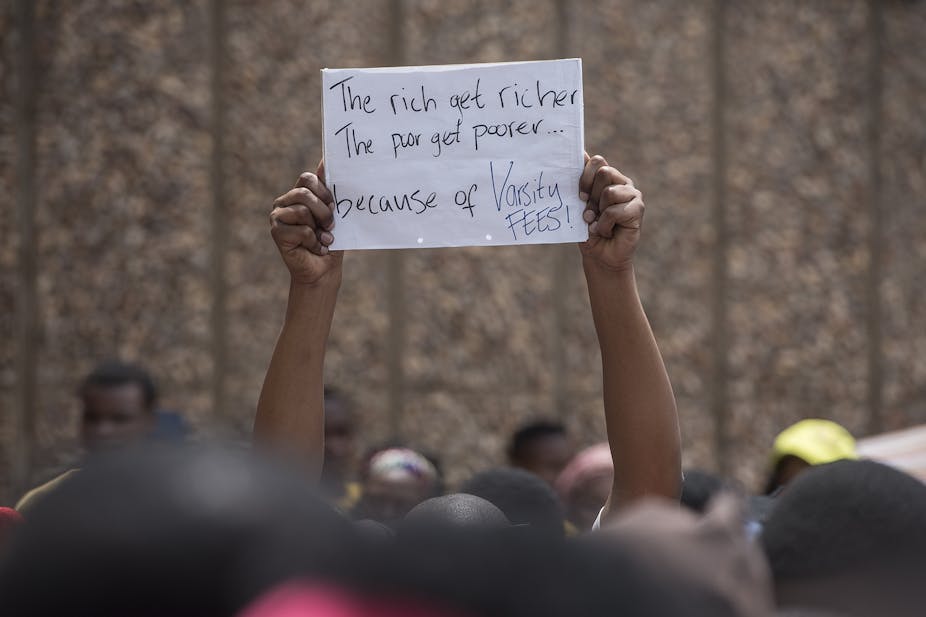

The idea of free higher public education, or what student activists have termed “#FeesMustFall”, is appealing. It is also, however, inherently regressive in societies and countries where massive social and economic inequities abound.

This is a not a new position. In 2002, myself and Professor Bruce Johnstone – one of the world’s pre-eminent scholars on financing higher education – contributed to a special issue of the Journal of Higher Education in Africa. In it, we pointed out that “free” public higher education never actually is free.

In Africa, there’s an array of heavily pressing and competing public needs. These include elementary and secondary education, public health and immense public infrastructure needs such as sanitation, water, housing, roads, telecommunications, a social safety net and public safety – among others.

This means that every additional public dollar, franc, cedi, shilling or rand spent on higher education is one that cannot be spent on these other urgent needs. This situation constitutes what economists call the “opportunity cost” of additional resources to higher education.

Higher education budgets in most African countries are already stretched to extremes. South Africa, which has been the site of #FeesMustFall protests since late 2015, is no exception. There’s been a massive growth of government funding to universities from R9.8 billion in 2004-05 to R24.8 billion in 2012-13.

The government’s purse is straining.

Governments can raise additional revenue either by borrowing or by raising taxes. South Africa, like other countries in Africa, is at the limits on both.

Universities under pressure

A major portion of government revenue is typically generated through taxation from both the indigent and the affluent. Such revenue, along with any that is borrowed from global financial institutions, is then distributed to public institutions. This process presumably happens according to a country’s national plan and its priorities.

There is little or no way in the current economic climate for most African governments to raise additional higher educational revenue through increased taxes or more governmental borrowing.

Universities’ financial constraints have driven a discussion in the past decade about revenue diversification. This supplements the increasingly scarce revenue obtained through tax or borrowing. It could come through entrepreneurship by a faculty or institution. It could also be generated through cost-sharing – that is, by passing some of the additional costs on to parents, guardians and students.

In Africa, a hugely disproportionate number of university students come from upper and middle income families. Malawi is an extreme case. It is one of the world’s poorest countries and more than 90% of those in higher education come from the highest income quintile.

South Africa has a greater population and a much larger middle and upper class population. Still, parallel – but comparable – patterns are easy to contemplate.

No ‘blanket amnesty’

Such inherent inequalities and inequities render the argument students are making for a blanket free education for all simply unfair – and unjust. If it’s free for all, the whole society ends up paying more.

A quixotic slogan such as “free education for all” may make sense in countries like Norway and Finland. There, the economic stratification is more just and the social safety strands more robust. Similar approaches may also be relevant for countries which are either emerging from a massive national crisis or starting from scratch.

But in a society like South Africa, there should be no rationale for a barefooted peasant to subsidise the university education of the children of the “well-heeled”. They are, after all, already enjoying advantaged, and privileged, upbringing and education. A “blanket amnesty” – free education for all – must not be granted to affluent students.

Instead, parents, at least those who are financially able, and students – at least those who are able to take loans at reasonable rates of interest – should share the rising costs of higher education along with the general taxpayer.

And different forms of funding higher education – businesses, NGOs, foundations, alumni – must also be pursued.

A more robust means-testing, effective loan-provision and aggressive loan-recovery schemes must also be put in place. It is no-brainer that not everyone is cut out for university education and individuals have to be realistic in their expectations and governments pragmatic in rendering and executing their policies.

The International Journal of African Higher Education will soon publish a piece by Johnstone that provides an excellent analysis and recommendation on student loan issues in Africa. It follows from already published research in which he explored the same issue in all low- and middle-income countries.

Heavy costs

In our 2002 article, Johnstone and I concluded that any forms of cost-sharing are not easy solutions, either technically or politically.

Consequently, there is no easy or obvious solution to the financial dilemma of higher education. Anyone is going to come with heavy opportunity costs and political costs.

This article is based on a piece written for the International Network for Higher Education in Africa, of which Professor Damtew Teferra is the founding director.