The recent elections in the UK have been hailed as another success for the Conservative party. The headline loss for Labour in 2021 was the Hartlepool by-election – but it also ceded control of councils across the country. After over a decade in government, overseeing the biggest reductions in public spending since the second world war, it is remarkable that the Conservatives continue to enjoy such strong electoral support.

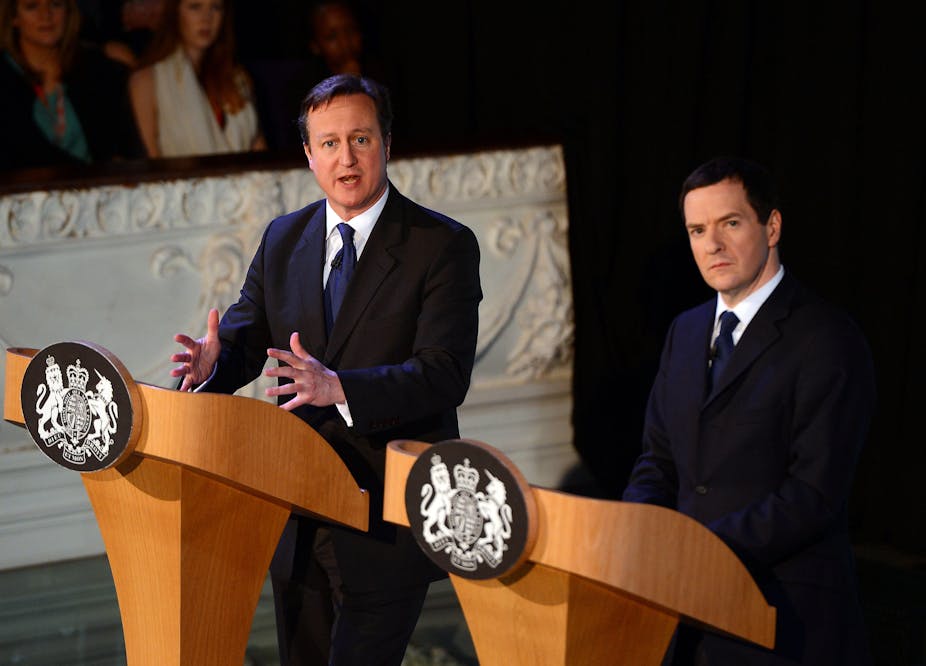

Spending cuts implemented under the Conservatives have inflicted considerable damage on many areas of the public sector, particularly in the years of austerity instigated by former prime minister David Cameron. Those living in poverty and with disabilities have been hardest hit, despite the UN special rapporteur’s damning finding that “austerity could easily have spared the poor, if the political will had existed to do so”.

While uncertainty remains about the direction of the post-COVID economy, austerity continues to bite for many areas of government.

After 11 years of cuts, why has there not been a stronger backlash at the ballot box? One answer may lie in the way the government has talked about austerity. Both the coalition government of 2010-2015 and subsequent Conservative governments have spoken of austerity as necessary and unavoidable. In 2010, Cameron claimed that “we are not doing this because we want to, driven by theory or ideology. We are doing this because we have to”.

However, this claim is misleading. Many economists view austerity as an ideological choice to reduce the size of the state, attributing debt caused by bank bailouts to overspending in the public sector.

Beyond the economics, politicians justified cuts to welfare by framing them as necessary to combat “benefit scroungers”. In doing so, they made it seem as though poor and disabled people deserved the cuts, unlike worthy “taxpayers” – despite tax fraud costing the country nearly 12 times more than benefit fraud.

How people think about austerity

One consequence of this narrative has been to divide attitudes to the cuts. My research finds that voters typically fall into one of four camps: people who are pro-austerity, austerity sceptics, people who are inactively anti-austerity and people who are actively anti-austerity.

The last group are a small minority. They are often members of left-wing political parties and vocally oppose both the justification and implementation of cuts. The pro-austerity group, in contrast, accept the government’s arguments and see no reason to oppose austerity. But, typically, they have felt the cuts only through longer GP waiting times and more potholes in the roads.

Many austerity sceptics dislike the way cuts have been implemented, having been personally affected or knowing others who have been. They are more aware of the unequal impact of cuts and tend to reject the idea that we are “all in it together”. However, for them, it is not clear that it would actually be right to stop austerity.

Government language around “reducing the deficit” has been linked to the idea that household debt is fundamentally problematic. Intuitively, therefore, some people accept the idea that cuts are necessary even if they aren’t desirable. The government capitalised on this misleading comparison to household budgeting, ignoring key differences such as the government’s ability to borrow through low interest bonds or raise taxes.

For those subject to benefits sanctions and underfunded social care, the government narrative has been stifling. They usually fall into the inactively anti-austerity group. For them, the idea that there is no alternative to cuts inhibits opposition because it appears change simply isn’t possible. As one person said to me, “I just don’t think anything will be done.”

Lack of opposition

But what about Labour? Opposition to austerity was a theme under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. However, his tenure as leader began more than five years after the onset of austerity. Prior to this, there was no meaningful opposition to the cuts from the Labour party. In fact, it proposed spending reductions in its 2010 and 2015 election manifestos.

There was also no clear attempt to challenge the government’s rhetoric around welfare claimants or the necessity of austerity in general. While Keir Starmer has expressed some opposition to future spending cuts, he has been criticised for a lack of clarity on what he stands for.

Without strong opposition, the austerity narrative has been highly persuasive. It is widely accepted as something that “had to be done”, garnering support among those less affected by cuts. Those facing poverty, health problems and food insecurity are often already reluctant or unable to engage in politics.

However, this lack of political voice can exacerbate the challenges they face as they are unable to stand up for what they need. Meanwhile, the Conservatives continue to enjoy a reputation as fiscally prudent, with little challenge to their policies. It is therefore crucial that we question the language the government uses to talk about its decisions and its influence on the way we think about politics.