The great basketball writer Jackie MacMullan recently stood at the front of a hotel ballroom in Tampa taking questions after collecting a career achievement award from the Association for Women in Sports Media.

I was in the audience that day. Initially, the questions focused on her early days in basketball as a reporter. But then someone brought up a series of stories MacMullan had written for ESPN last summer on NBA players’ mental health problems. MacMullan called it “probably the most important thing I’ve ever done,” and a nearly 10-minute discussion followed.

The package featured All-Stars Kevin Love and Paul Pierce, among others, discussing their struggles with depression and anxiety. Other big names backed out at the last minute, concerned about the stigma of mental illness and whether it might hurt their ability to land a good contract in free agency, a point MacMullan emphasized when we spoke after the session ended. She said a league source called the problem “rampant.”

It’s not just the NBA where athletes’ struggles with mental health are under scrutiny, either. As the director of the John Curley Center for Sports Journalism at Penn State University, I’ve noticed that mental health and sports is a topic gaining attention among athletes and the journalists who cover them.

Wanting to explore why it’s happening now and why it matters, I talked to some experts in the field.

Pro athletes are particularly susceptible

Listing every publicly known example of an athlete dealing with a mental health issue would be a tough task, but it’s clear that neither the particular sport nor an athlete’s gender makes someone immune.

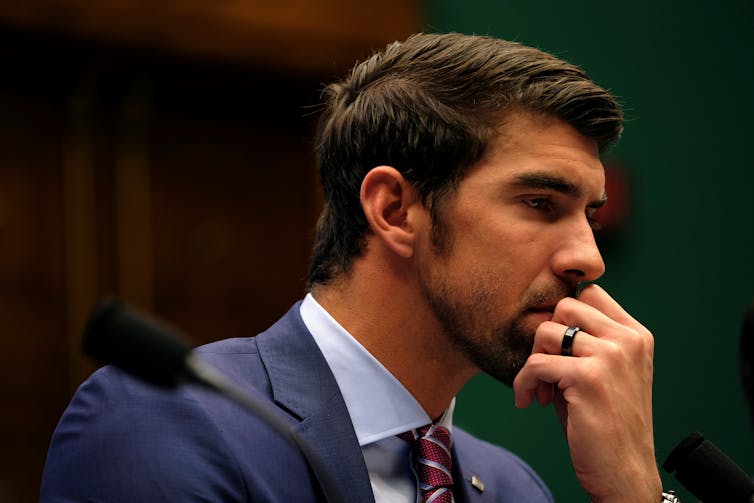

Michael Phelps – a swimmer with more medals than anyone in Olympic history – has spoken candidly for years about his struggles with depression. Longtime NFL receiver Brandon Marshall has gone public with his mental health issues, as has 2012 Olympic silver medalist in high jump Brigetta Barrett. Fox Sports has written about the frequency of eating disorders among female college athletes.

Experts I spoke with for this story pointed to a couple of reasons professional athletes are particularly susceptible to mental health issues.

Many “are high-achieving perfectionists,” said David Yukelson, the retired director of sports psychology services for Penn State Athletics and a past president of the Association for Applied Sports Psychology.

That’s great when it all comes together in victory or a terrific performance, but the toll of perfectionism can be tough when the results don’t match an athlete’s own expectations, Yukelson said.

Playing sports in the age of anxiety

The visibility of today’s elite athletes exacerbates the pressure.

Scott Goldman, president-elect of the Association for Applied Sport Psychology, told me it’s hard for fans to understand what it’s like to constantly be in the spotlight. He recalled watching a pro football player prepare to run onto the field and wonder aloud whether anyone else in the building had people howling at them when they went to work.

Add social media to the mix, and all the armchair experts that brings to any sports discussion. Earlier this year, NBA Commissioner Adam Silver told the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference: “We are living in a time of anxiety. I think it’s a direct result of social media. A lot of players are unhappy.”

The NBA has responded to the problem with a series of initiatives designed to help players cultivate mental wellness. Beyond compassion, the efforts make business sense: Happier players lead to better-performing players, which leads to more wins.

Attention to mental health issues in sports also seems to be on the uptick in the United Kingdom, said Professor Matthew Smith, a historian at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow. Smith, whose research focuses on medicine and mental health, has been tracking sports-mental health articles on the BBC for the last couple of years and noted the count recently topped 100 stories.

He highlighted the suicide of Wales national men’s soccer team manager Gary Speed in 2011 as a watershed moment that catalyzed the country’s awareness and that still makes headlines.

Fast forward to this May, when England’s Football Association revealed a campaign to show that “mental fitness is just as important as physical fitness,” with Prince William making the public announcement.

Takeaways for athletes and fans

Back in the United States, some wonder whether athletes are opening up about mental health issues because rates of such problems are rising among young adults, or if it’s simply become more acceptable to talk about the issue.

Yukelson said times certainly have changed from the 20th century, when athletes were expected to absorb every setback and insult on their own. There’s more support now. The Association for Applied Sport Psychology, a group for sport psychology consultants and professionals who work with athletes, coaches and nonsport performers, was founded only in 1985. It now has 2,200 members worldwide, according to Emily Schoenbaechler, the group’s certification and communications manager.

Goldman, meanwhile, compared the situation to not knowing you have a cockroach problem until you turn on a light. In other words, drawing attention to an issue makes more people aware it exists.

But it’s also true that nearly one in five American adults has a mental illness, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. That’s more than 46 million people.

Both Goldman and Yukelson noted that only good things can come from athletes opening up about the issue. The more athletes talk, the more fans might feel inspired to seek help on their own.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness lists talking openly about mental health as the first way to reduce stigma. And an early advocate for speaking out about players’ mental health, Metta World Peace – who changed his name from Ron Artest in 2011 – notes that when he first talked about his struggles, the media thought he was “crazy.” Now the default is to call for getting the athlete some help, he says.

It all points to changing attitudes in sports – and society.

Or as Phelps put it in a recent tweet, “getting help is a sign of strength, not weakness.”