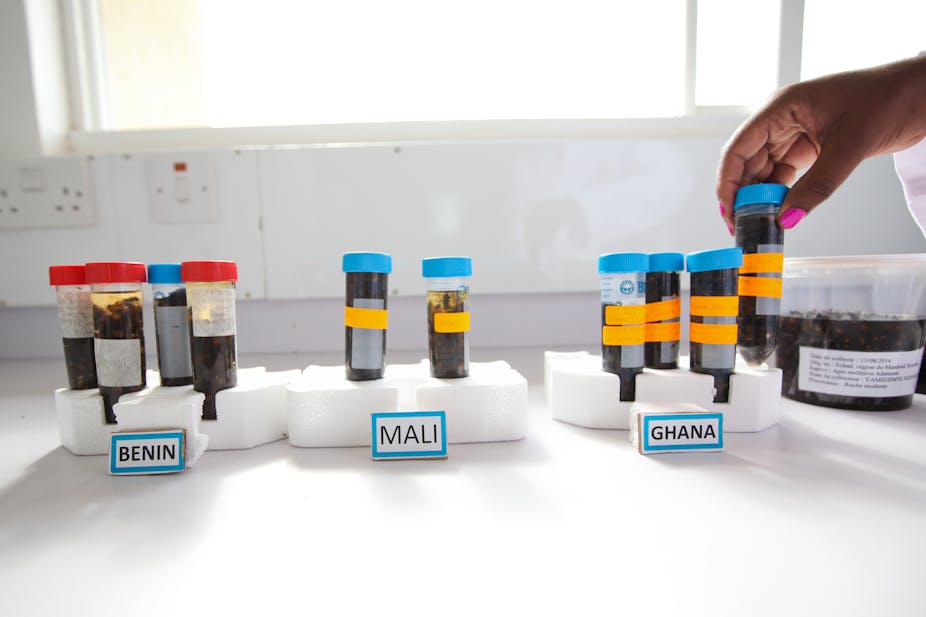

Seven years ago Bassirou Bonfoh, the director of the Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifique in Cote d’Ivoire, joined forces with 10 other African institutions. Their plan was to collaborate on research into infections that pass between animals and humans. Many of these infections, such as Ebola, Zika and HIV, are sadly world famous.

The collaboration enabled Bonfoh to access data from as far afield as Tanzania and extend his remit to rift valley fever, an infection that has had several outbreaks since it was first detected in 1931.

Crucially, throughout this collaboration, Bonfoh has avoided duplicating research. This is rare in Africa. Even though most African countries face similar health and developmental challenges, researchers work in silos. This wastes limited human resources and infrastructure. It also means that researchers are competing for a small pool of grants and decreasing their chances of success. A 2010 report by Thomson Reuters found that of the continent’s six stronger research nations – Algeria, Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Tunisia — not one had an African country among its top five collaborating countries.

Why is collaboration so crucial? Bonfoh’s experience shows that it ensures more scientists are trained and knowledge is generated that can be fed into policymaking processes. Bonfoh’s group has trained 12 postdoctoral fellows and 45 Masters and PhD students from 2010 to date. The collaboration he was part of involved 11 African research centres and universities conducting zoonosis research and training postgraduate students in the field.

Sadly, this story is rare. There are a number of stumbling blocks to intra African collaboration that must be urgently addressed.

Barriers to sharing

Geographical and political barriers prevent Africans from working together. For instance, when Bonfoh organised a meeting in 2013 he had to negotiate with his government to arrange for visas on arrival for his peers from countries without Ivorian embassies. This problem is replicated all over the continent.

Allowing the free movement of researchers is necessary for networking, which is the foundation of collaboration. Unlike people, diseases and developmental challenges don’t know geographical barriers and their spread has come at a tremendous cost for the continent.

The Ebola outbreak of 2014 and 2015 provides a good example. It caused an estimated loss of $2.2bn to the already hard hit economies of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. The outbreak wasn’t new to Africa: there had previously been similar ones in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. But the absence of intra Africa collaboration meant lessons could not easily be shared so the human and economic loss could not be avoided.

This is what we need to change.

Pooling human resources and providing people with career opportunities is important. PhD supervisors in Africa are a scarce commodity, and institutions must pull together to train future scientists. Otherwise, Africa will continue losing thousands of professionals every year to developed countries. Africans scientists who leave are often frustrated by the lack of infrastructure and mentors.

This is why programmes funding research in Africa must be deliberate about promoting collaboration across the continent. One example of a programme that is getting this right is the Developing Excellence in Leadership, Training and Science Africa Initiative (DELTAS). It is supporting large networks and consortiums – 11 programmes spanning 21 countries. There are 40 lead and partner institutions all collaborating to address emerging, infectious diseases as well as non-communicable diseases.

Another example is the Heredity and Health in Africa Consortium, funded by the Wellcome Trust and the US National Institutes of Health. This involves 24 collaborative projects conducting genomics research at institutions across the continent. There’s also the Climate Impact Research Capacity and Leadership Enhancement programme. This is being implemented by the African Academy of Sciences and the Association of Commonwealth Universities. It offers fellowships to post-Master’s and postdoctoral researchers to spend a year in institutions outside their own studying the impact of climate change on the continent with the aim of facilitating intra-African collaboration.

It’s also important to overcome language barriers that have left researchers oblivious of each other’s work. Researchers in Francophone Africa do not always read African research published in English especially if it is not translated into French. Unfortunately this means researchers working in the same field of research don’t know each other. Intra-regional collaboration provides a platform for scientists from Anglo and Francophone Africa to share their work.

Power of the collective

Lastly, collaboration will help to mobilise political support for research. Projects that have wide continental relevance are more likely to be adopted at African Union and the NEPAD agency level than those that are focused on only one country.

And there is power in speaking collectively. Researchers need the support of the African Union to lobby for more government funding and improve Africa’s spend on research and development. This is currently just 1.3% of the total global spend. Increased investment should provide the surveillance systems and other resources to enable Africa to address its problems before they spiral out of control and result in huge financial losses or spread globally.

Bonfoh’s programme is already demonstrating the impact of collaboration. His network shows that the solutions to the most urgent health problems can come from within the continent, not outside it.

Walking together

Africa must take the initiative to lead its science and developmental agenda even as it receives global support. Collaboration will amalgamate different voices and ideas to promote and conduct research relevant to the continent’s needs. As the African saying goes:

If you want to go fast walk alone, and if you want to go far walk together.

This article is based on a blog post that originally appeared on the Financial Times’ website.