In an election campaign full of giveaways but short on serious economic reform, Labor’s proposed change to childcare support is the most important economic news.

It fits in with this year’s Grattan Institute Commonwealth Orange Book, which identified getting more women into the workforce as one of the most valuable things the next government could do.

Female participation in the labour force is lower in Australia than in similar countries. It is particularly low for women working full-time.

That’s because motherhood hurts female participation more in Australia than in other countries. Before having children, Australian women are just as likely to work as men. On having children, many drop out of work and some never go back. Those who do return often pay a career penalty.

Childcare is the biggest barrier to work

Childcare is the highest hurdle. When surveyed, more than 40% of Australian women who would like more work say caring for children and its cost are the main reasons they can’t take on more hours over the coming weeks.

Women with children get relatively little financial reward for entering the workforce, and even less for working more hours. Some find working more hours costs more than it pays.

They face high effective marginal tax rates because as they work more hours they lose more family and childcare benefits as well as paying more income tax. Factoring in the cost of childcare itself, some face costs exceeding 100% of what they earn.

Here the Coalition deserves some credit. Its previous reforms to the childcare subsidy helped reduce effective marginal tax rates.

But there’s still a long way to go, with many mothers still facing very high effective rates.

Effective tax rates make returning expensive

A woman in a low-income household still loses 85 to 95 cents of every extra dollar she earns if she increases her work days from three to four, or from four to five.

Even women in middle earning households face effective marginal tax rates near 80% if they move from four days paid work per week to five.

These effective marginal rates are much higher than the headline marginal tax rate paid by those earning more than A$180,000 per year, which is the focus of many who purport to be worried about the impact of tax rates on incentives to work.

Labor will make work pay better

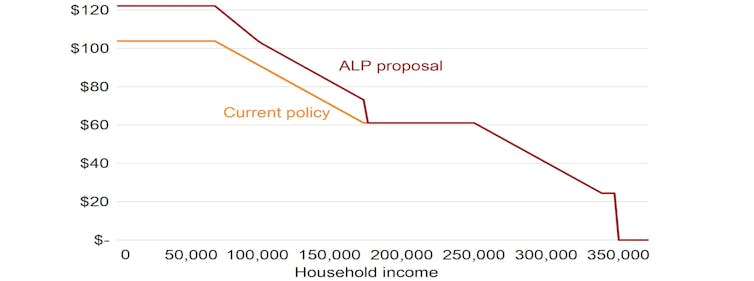

Under Labor’s proposal, childcare will become free for families with incomes of up to $69,000 a year, up to the hourly cap of $11.77 an hour, or $141 a day.

Families on higher incomes will still have to pay some of their childcare costs, but less than they do today.

Child care subsidy per child in care per day, 2020-21

The savings per extra day worked would be substantial.

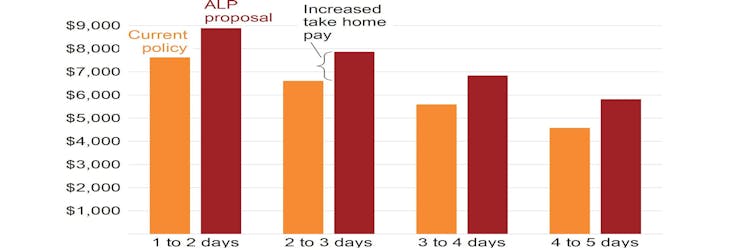

Consider a middle-income family with two children in childcare: a primary earner bringing in the average full-time wage of $95,103 in 2020-21, and the other choosing how many days to work in a week in a job that would pay the median full-time wage of $61,000.

Labor’s plan would increase the reward for working an extra day a week by about $1,260 a year.

It would give that second earner an extra 10 cents out of every extra dollar she earns.

Gross earnings less childcare costs net of subsidy if second earner works an extra day

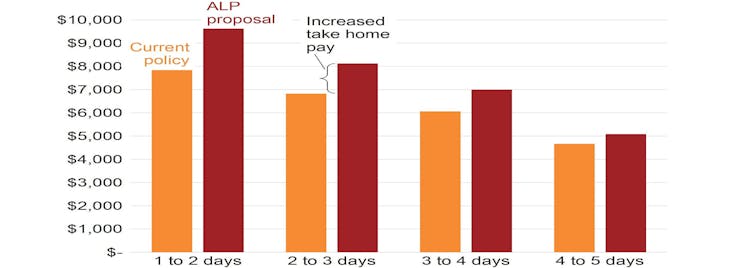

Now consider a lower-income family with a primary earner on $50,000 a year and a secondary earner in a job that also pays $50,000 a year full time, again with two children in childcare.

Labor’s plan will boost the reward for working two days a week rather than one by around $1,784 a year. That worker would be keeping an extra 18 cents out of every extra dollar she earned. The change would be more than big enough to lead many families to make different decisions about work.

The change will be smaller when the second income earner goes from working four days a week to five, because the subsidy tapers out. For this low income family, Labor’s plan would boost the reward for working four days rather than five by only $421, a four cents in the dollar improvement.

Gross earnings less childcare costs net of subsidy if second earner works an extra day

Again, the change is a big deal.

These improvements in effective marginal tax rates are much larger than those offered by the actual tax plans of either major party.

And the empirical evidence also suggests women caring for younger children are more sensitive than others to effective marginal tax rates, and more likely to change their decisions about working if effective marginal tax rates change.

It means Labor’s childcare plan is likely to provide a bigger economic kick for each dollar spent than either of the two sides’ proposed tax cuts.

The policy isn’t perfect

Some aspects need more work.

Labor plans to cut the subsidy suddenly from 60% to 50% for families with incomes above $174,527. The cliff will distort incentives to work for some second earners, because they’ll instantly have to pay a lot more for childcare – around an extra $5,000 a year more – the moment their household income climbs a dollar over $174,527.

Read more: The budget's dirty secret is the tax hikes you're not meant to know about

A better approach would be to gradually reduce the subsidy rate from 60% for incomes of $174,527 to 50% for incomes above $205,000.

Childcare centres could raise their fees

Labor will also have to be careful to ensure its higher subsidies don’t simply result in childcare centres jacking up their prices and providing little benefit to families.

The existing cap on childcare subsidies of $11.77 per hour will limit any childcare fee increases. But Australians paid an average of just $9.20 per hour in 2018.

If the subsidies are higher so that many families only pay a small fraction of the cost of childcare, childcare providers will be very tempted to increase their fees up to the cap, and perhaps further. Centres serving lots of low-income families – who in many cases will pay nothing for childcare – will be particularly tempted.

Labor says it will ask the Competition and Consumer Commission to crack down on fee increases and to find ways to control child care fee increases in future. But past attempts to use the ACCC to police prices, such as during the introduction of the goods and services tax and the carbon tax, have had mixed success.

But overall, it’s a large and worthwhile reform

But overall, much of the increased subsidy is likely to be passed on to parents.

While there are limits to how much governments can influence economic growth, there are some worthwhile reforms they can pursue.

With its new childcare policy, Labor has produced one of the best there is.

Read more: Grattan Orange Book. What the election should be about: priorities for the next government