Indigenous students remain vastly underrepresented in higher education in Australia. According to Universities Australia, Indigenous people comprise 2.7% of Australia’s working age population but only 1.6% of university domestic student enrolments.

In the past decade, there have been renewed efforts to increase the participation of underrepresented groups in higher education, including Indigenous people. However, most policies have focused on raising the aspirations of students from low socioeconomic (SES) backgrounds. The particular aspirations of Indigenous students have been largely overlooked.

To address this, we put the spotlight on the aspirations of Indigenous students in a recent large-scale longitudinal study. Our research has made two quite significant discoveries.

Indigenous children have the same career aspirations as non-Indigenous children

The study revealed that from an early age, Indigenous children share the same aspirations as non-Indigenous children. This includes the desire to become doctors, teachers, vets and artists.

This finding busts the myth that we need to “raise” aspirations. As we see it, the focus of equity programs for Indigenous children should shift to nurturing the strong aspirations children already have in primary school.

No doubt many Indigenous children will change their minds as they grow up. However, our research suggests that waiting until senior secondary school to talk to them about their career aspirations is far too late. (The same is true for non-Indigenous children.)

High-achieving Indigenous children are less likely to want to go to university

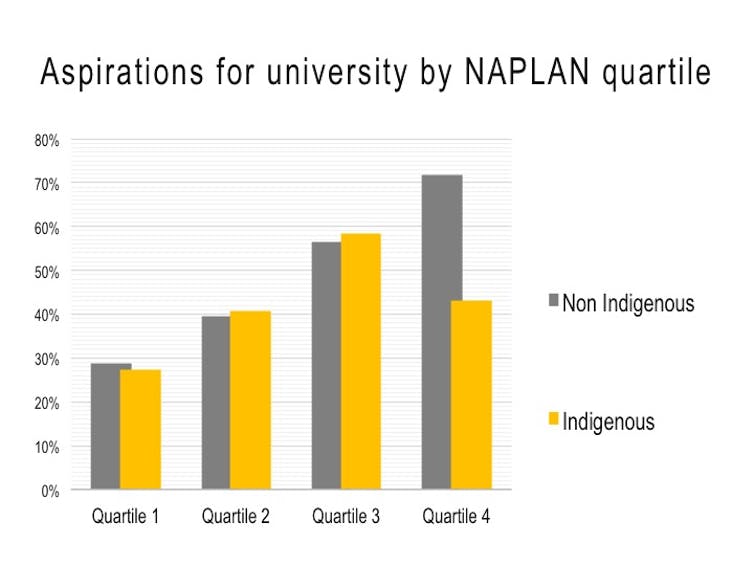

Perhaps more startling, our research found that high-achieving Indigenous students were significantly less likely to want to go to university than their high-achieving non-Indigenous peers.

While 72% of non-Indigenous students in the top NAPLAN quartile aspired to go to university, only 43% of Indigenous students in the same quartile said they wanted to go.

This indicates something is going wrong.

Why Indigenous kids aren’t choosing university

From understanding university pathways to managing the costs, there are myriad issues that influence the decision to go to university.

However, for Indigenous students, aspiring to university is likely to require negotiation of race, class, economic, and cultural divides in ways that are not shared by non-Indigenous students.

1) Cultural and geographic reasons

The majority of Indigenous children live in major cities and regional areas. But compared with non-Indigenous children, a larger proportion of Indigenous children live in remote and very remote parts of Australia. Across these geographic areas, bonds and commitment to country, community, and family are deeply felt.

It is also likely high-achieving Indigenous children will carry significant financial obligations in these familial relationships. They can be reluctant to relocate for university because of these ties.

2) Social and racial isolation

While universities connect with Indigenous school students through campus visits and mentoring programs, the lack of a sizeable cohort of Indigenous university students is likely to make the prospect of choosing university even more daunting.

More broadly, the lack of a sizeable Indigenous middle class means that socially mobile Indigenous people “may become stranded in a racially bound social capital wasteland” with gains in economic capital not necessarily leading to the kinds of social and cultural capital that traditionally benefit non-Indigenous people.

Further, Indigenous students may not want to expose themselves to racism and the racial divide apparent in the university, town or city where available universities are situated.

3. First -in-family

Many high-achieving Indigenous students would be the first in their families to attend university. First-in-family students face unique challenges because, by definition, they tend not to have the family or community experience to guide them. Moreover, many Indigenous students are the first in their families to complete secondary school, so university education might be a more alien concept.

4. Pathways, costs and financial support

Negotiating the fees and support available to Indigenous students can be difficult. There is a plethora of programs, scholarships, courses and accommodation choices, which can be overwhelming for a new student (especially with the other factors outlined above). This is something to take into account in the transition to university for Indigenous students.

5. No obvious benefit

High-achieving Indigenous students can “weigh up” the benefits of a university education and decide it is not “worth it” economically or socially. The risks and challenges they will face by leaving country, community and family might be seen as too high a price to pay. If study at TAFE or paid work is available locally these might be more desirable.

6. Distrust of government institutions

Indigenous students may have a deep (and justified) distrust of universities, given the past treatment of Indigenous people by government and non-Indigenous institutions.

No matter how welcoming or how strong the Indigenous support centres on campuses, some Indigenous families will struggle to see university as a place for them or their children.

Breaking down the barriers

Higher education does not exist in a vacuum. There are things that can be done to address these issues.

One step is to pay more attention to the aspirations of Indigenous students in the early years and how those aspirations are formed in relation to existing social, cultural, economic, and racial divides.

Another step is for universities to reconceptualise their outreach strategies targeting Indigenous students. There should be more consideration paid to the factors outlined above.

Fundamentally, it is not just about making higher education possible, but rather, making university a place where Indigenous young people will want to pursue and attain their occupational aspirations.