In the history of science during the Dutch colonial era, the role of native Indonesians is often ignored due to the strong colonial narratives in history writing.

This kind of narrative sees history from the viewpoint of colonisers. They often marginalise the existence of those they colonise even though a number of written sources state that native Indonesians possess capable knowledge.

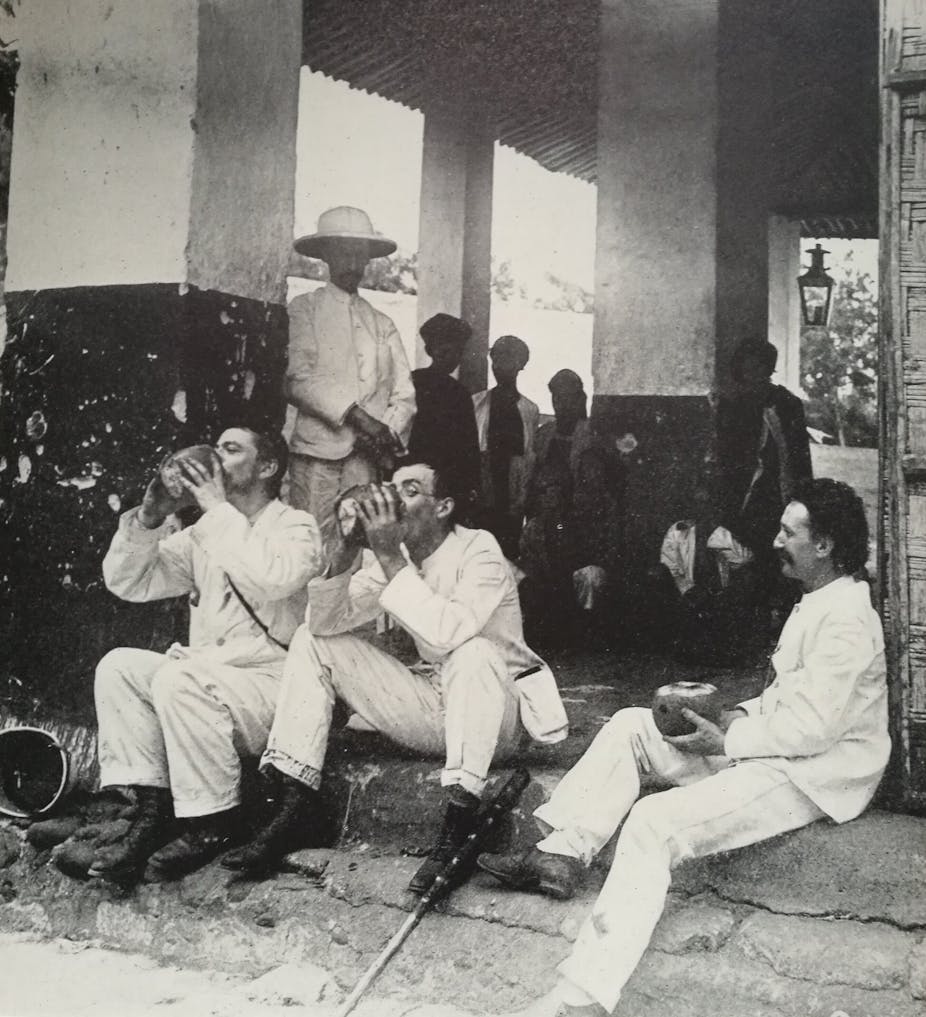

In his autobiography The World was My Garden: Travels of a Plant Explorer, David Fairchild, an American botanist and zoologist, mentioned the names of several native Indonesians who helped him during his visit to the then Dutch East Indies in 1895. He was invited by Melcior Treub, director of the Bogor Botanical Gardens, to conduct research.

In his book, Fairchild praised Oedam, the head gardener at the Bogor Botanical Gardens, as “an outstanding botanist in all aspects”. He was amazed because Oedam remembered every plant in the gardens. Not only did Oedam remember the local names of those plants, he also remembered its genus and species under the European system.

Besides Oedam, there was Mario, a local assistant chosen specifically for Fairchild. Mario was considered competent because he had skills in using modern equipment that was used to support the research.

Fairchild also met Papa Iidan who collected materials for scientists and knew more about insects than he did.

Henry Ogg Forbes, a scientist from Scotland who studied tropical plants and animals in the Dutch East Indies from 1878 until 1883, had similar opinions of local expertise.

Forbes was impressed by the people of Banten, a region in the western part of Java island. He discovered they were highly intelligent and amazing observers. In his essay “Through Bantam”, published in Science and Scientists in the Netherlands Indies, Forbes praised the local people’s knowledge in providing him with names of local plants and animals organised in ways resembling the European system.

In The Brokered World: Go-Betweens and Global Intelligence 1770-1820, Simon Schaffer, a professor of the history and philosophy of British science, explained that people like Oedam, Mario and Papa Iidan are intermediaries (go-betweens) connecting Western scientists and local knowledge.

Although their role is important, this group is often missing from the narrative of colonial history. This article will explain why it happened.

The West is at the centre

One of the reasons this happened is because the history of science is still discussed from a one-sided, Western perspective. This perspective – at that time belonging to the majority – stated that Europeans were the ones to actively produce and spread science, whereas non-Europeans could only act as passive recipients.

George Basalla, an American science historian and proponent of this view, wrote in his essay that the stage of spreading science to non-European regions happened in one direction.

Basalla divided the spread of science into three stages: exploration, the production of colonial science, and the formation of independent scientific traditions.

In the first stage, the Europeans established contact with colonies to trade, conquer, or build new settlements.

The “non-scientific” societies they encountered served as a source of information for modern science. Information was collected in the form of maps and endemic flora and fauna specimens. This information was processed into a universally understood Western science. It was then brought “back” to the colonial regions for further development.

The second stage is marked by an increase of scientific activities in the colonial regions. European scientists established local institutions and entirely replicated scientific investigations commonly carried out in Europe. In this way, they could conduct more effective research closer to their subject matter.

In the third stage, along with the emergence of nationalist movements, colonial science gradually developed into an independent scientific tradition in the country of origin. Colonial scientists were replaced by “native” people who were trained in science and worked within national borders. Knowledge from those countries was considered to have been handed over.

Criticism of colonial narratives

Basella’s model received strong criticism because it assumed the centre of knowledge lies in Western European countries. For Basella, there is no axis for knowledge other than countries in that region. Therefore, Basalla used the term diffusion instead of collaboration.

In the case of the Dutch East Indies, Basalla’s model is inaccurate. The first stage shows strong evidence of collaboration, rather than diffusion. This is the phase where scientists deemed equal could exchange information with one another. This process was carried out through an intense two-way communication.

We can see the dynamics of this relationship in the communication between Fairchild and his local assistants, as well as Forbes with the people of Banten.

Georg Everhard Rumpf (Rumphius), a 17th-century German scientist, also gave credit to local residents who assisted his research on plants in the Indonesian archipelago.

However, such practices were not common at the time.

Changing the narrative

The unequal relationship between colonisers and the colonised people have become “the spirits” of the written documents made during the colonial era.

Ann Stoler, an American professor of anthropology and history studies, has shown that those colonial archives are not neutral. However, the writing of historical works often depends on this type of document. As a result, the narrative is built upon the perspective of the colonisers who often leave out the colonised people from the main narrative.

The interactions between colonisers and the colonised are more complex than just a one-way communication. There is another aspect related to cooperation in scientific development, the role of intermediaries, which isn’t seen in the colonial narrative.

Attempts to place these intermediaries into the unequal narrative of colonial history must be made. Personal records from people such as Forbes and Fairchild can help this process.

Ayesha Muna translated this article from Indonesian language.