The stakes are high for Marvel and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates to do Black Panther well. The character appears this month in the blockbuster “Captain America: Civil War,” a prelude to the film he’ll headline in 2018. And last month, Coates released the first issue of a new Black Panther comic series.

When it was first reported last September that Coates would script a 12-issue arc of the Black Panther, some commentators suggested that he might be an “odd” fit.

The implication was that a MacArthur Genius Grant recipient and winner of the National Book Award was participating in a genre and medium beneath his talents. But they might be surprised to learn discussions of racism in superhero comics is a long – albeit often troubled – tradition. They also might not recognize the extent of Coates’ literary undertaking. He is tasked not only with appealing to comics readers but also with attracting new fans to the genre. This would be a daunting prospect, no matter the property. But the Black Panther character poses a very specific set of challenges.

Beyond Tarzan

When T’Challa (the Black Panther) first appeared in The Fantastic Four comic book in 1966, it was at the tail end of what Bayard Rustin termed the “classical” phase of the civil rights movement: the era between Brown v. Board of Education and the passage of the Voting Rights Act. T'Challa marked the first of a number of attempts to produce more progressive, less racist representations of black people in comics. While many of these early characters, like Luke Cage, still often trafficked in stereotype, the Black Panther was arguably more successful in highlighting the prejudices the West holds about Africans and African nations.

T’Challa is king of the fictional African nation Wakanda, a wealthy and technologically advanced country. While not devoid of problematic representations of Africans, the comic criticized a Western, white gaze that can’t imagine that a technologically advanced African nation could exist. Initially, Black Panther still had some of the conventions of the “jungle comic,” but a black protagonist was a major step away from white heroes like Tarzan and Sheena who were worshipped by the ignorant “natives.”

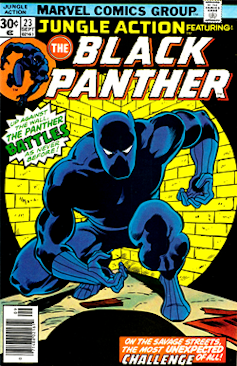

Don McGregor is arguably Black Panther’s most celebrated writer for challenging the conventions of not only racial representations in comics but the comic book storytelling format itself. The “Panther’s Rage” story was told over the course of several issues, which is now a common convention in comics. He is renowned for featuring an all-black cast in a mainstream comic and not seeing white characters as necessary to sell the story. McGregor wanted to push back against the racist conventions of jungle comics.

Decades later, Black Panther writers Christopher Priest and Reginald Hudlin continue to plumb this theme. Many Westerners still see Africa as a country, not a continent; they fail to note differences between nations, or acknowledge how post-colonial conflicts in many African countries are as much a part of “modernity” as any developments in the West. The fact that, 50 years later, African-American writers would still be responding to the same stereotypes (albeit with much more barbed sophistication than in Stan Lee’s 1960s scripts) shows the persistence of these representations.

Beyond stereotype

One consequence of the long history of stereotypical representations of minorities and disadvantaged populations is that the line between stereotype and images that attempt to depict the struggles of these groups can be blurry. In the case of Africa, depictions of violence, war, corruption and poverty run the risk of being interpreted as representative of all Africans.

Superhero comics depend on conflict and need villains, thus any representation that draws on real life may run the risk of producing simplified depictions of African conflicts. While Black Panther’s most important villain is a character named Klaw, an archetypal white colonizer figure who wants to steal Wakanda’s natural resources, T'Challa faces many African foes as well. Villains like “Man-Ape” – a character who ate the flesh of an ape for his power and wants to return Wakanda to a primitive culture – are important in Black Panther’s history. While the character has been updated in recent years, he can still easily be read as a stereotype.

Not depicting some exaggerated variation of real-world conflicts can be equally problematic. While initially grounded in many urban struggles and the war in the 1930s and 1940s, superheroes increasingly fought supernatural villains after World War II. These fantastic battles can make comics seem like they’re ignoring important real issues. Black artists (and readers) might find that particularly vexing. While Black Panther’s creator and McGregor were not black, many people call Black Panther a black comic that speaks to issues important to the black community.

Scholars and artists have long debated what makes black art “black,” but many still believe what W.E.B. Du Bois argued in his 1926 essay “Criteria of Negro Art” – that black art should be “propaganda” in the sense that it promotes positive representations of black people. Du Bois was concerned both with “real” black experience and that black art should contest negative representations of blackness. Reams of writing over the years have contested this prescriptiveness, but many people still expect to see representations of blackness that they identify with and that black works contradict stereotypes.

Beyond comics

Coates is clearly interested in continuing the project of contesting stereotypes – racial, national and gender. He enters the series as a writer after the unprecedented run of a female Black Panther, and women play a major role in his first issue. The first issue does not provide much of a road map to where he is going, but history illustrates the challenges he faces in writing for this storied character.

Due to the pedigree he’s earned as an Atlantic Monthly columnist and with the award-winning “Between the World and Me,” he’s opening up comics to readers who are not comics fans, but who will expect him to be attentive to the criteria for black art. However, writing a comic book requires a specific skill set. Writers have a limited amount of words; much of it is dialogue. They must negotiate the relationship between compelling single issues and longer narrative arcs. And in the case of a major character like Black Panther, they must be attentive to decades of complicated backstory while crafting a narrative that is both respectful and original. Failure to produce a comic that’s intellectually engaging and entertaining would disappoint avid comic readers. For fans of Coates picking up a comic for the first time, it would be an indictment of the genre.

Meanwhile, for the film version, it will be the first time a black character will headline a film in the Marvel Universe.

A white superhero film failing has not caused studios to shy away from superhero films with white protagonists. The failure of a superhero film starring a woman or person of color, however, can set back the development of diverse superhero films for some time. Many people would probably rejoice in anything that stops the superhero franchise juggernaut. But the last few years have brought increased attention to the real struggles for women and people of color to break into the comics and film industries.

Unfortunately, when it comes to underrepresented populations, the success or failure of these texts always ends up being about more than the specific text in itself. It becomes a referendum on whether or not stories about people who are not straight, white men are valuable, and whether or not people who tell such stories should be given the resources to do so.